Questions to Consider Before You Start

Posing Productive Questions

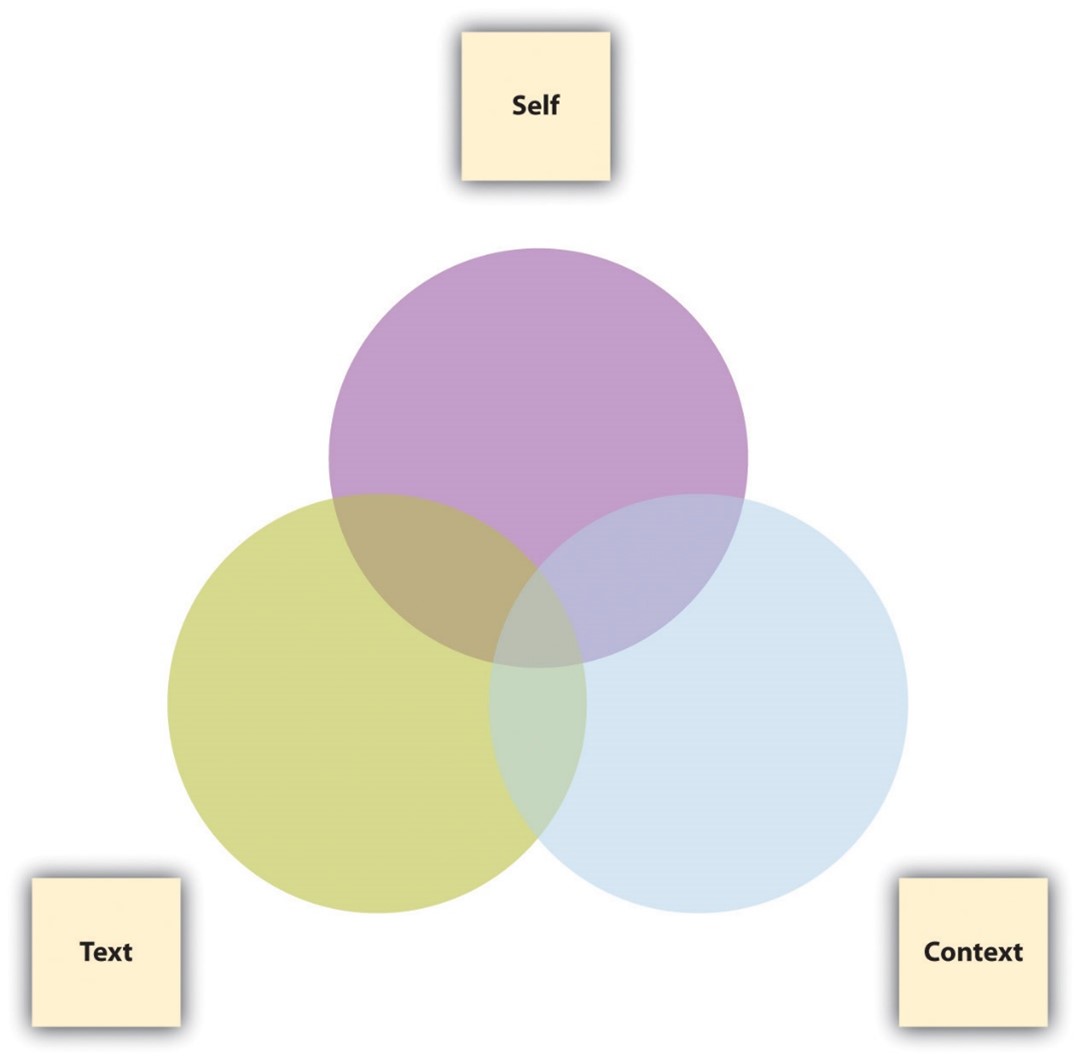

In this section, we’ll explore other ways to open up thinking and writing through the systematic process of critical inquiry. Essentially three elements are involved in any act of questioning:

- The self doing the questioning

- The text about which the questions are being asked

- The context of the text being questioned

For our purposes, text should be defined here very broadly as anything that can be subjected to analysis or interpretation, including but certainly not limited to written texts. Texts can be found everywhere, including but not limited to these areas:

- Music

- Film

- Television

- Video games

- Art and sculpture

- The Internet

- Modern technology

- Advertisement

- Public spaces and architecture

- Politics and government

The following Venn diagram is meant to suggest that relatively simple questions arise when any two out of three of these elements are implicated with each other, while the most complicated, productive questions arise when all three elements are taken into consideration.

Asking the following questions about practically any kind of text will lead to a wealth of ideas, insights, and possible essay topics. As a short assignment in a journal or blog, or perhaps as a group or whole-class exercise, try out these questions by filling in the blanks with a specific text under your examination, perhaps something as common and widely known as “Wikipedia” or “Facebook” or “Google” (for ideas about where to find other texts, see the first exercise at the end of this section).

Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context

Self-Text Questions

- What do I think about ____________?

- What do I feel about ___________?

- What do I understand or what puzzles me in or about ____________?

- What turns me off or amuses me in or about ____________?

- What is predictable or surprises me in or about ____________?

Text-Context Questions

- How is ___________ a product of its culture and historical moment?

- What might be important to know about the creator of ___________?

- How is ___________ affected by the genre and medium to which it belongs?

- What other texts in its genre and medium does ___________ resemble?

- How does ___________ distinguish itself from other texts in its genre and medium?

Self-Context Questions

- How have I developed my aesthetic sensibility (my tastes, my likes, and my dislikes)?

- How do I typically respond to absolutes or ambiguities in life or in art? Do I respond favorably to gray areas or do I like things more clear-cut?

- With what groups (ethnic, racial, religious, social, gendered, economic, nationalist, regional, etc.) do I identify?

- How have my social, political, and ethical opinions been formed?

- How do my attitudes toward the “great questions” (choice vs. necessity, nature vs. nurture, tradition vs. change, etc.) affect the way I look at the world?

Self-Text-Context Questions

- How does my personal, cultural, and social background affect my understanding of ________?

- What else might I need to learn about the culture, the historical moment, or the creator that produced ___________ in order to more fully understand it?

- What else about the genre or medium of ___________ might I need to learn in order to understand it better?

- How might ___________ look or sound different if it were produced in a different time or place?

- How might ___________ look or sound different if I were viewing it from a different perspective or identification?

We’ve been told there’s no such thing as a stupid question, but to call certain questions “productive” is to suggest that there’s such a thing as an unproductive question. When you ask rhetorical questions to which you already know the answer or that you expect your audience to answer in a certain way, are you questioning productively? Perhaps not, in the sense of knowledge creation, but you may still be accomplishing a rhetorical purpose. And sometimes even rhetorical questions can produce knowledge. Let’s say you ask your sister, “How can someone as intelligent as you are do such self-destructive things?” Maybe you’re merely trying to direct your sister’s attention to her self-destructive behavior, but upon reflection, the question could actually trigger some productive self-examination on her part.

Hypothetical questions, at first glance, might also seem unproductive since they are usually founded on something that hasn’t happened yet and may never happen. Politicians and debaters try to steer clear of answering them but often ask them of their opponents for rhetorical effect. If we think of hypothetical questions merely as speculative ploys, we may discount their productive possibilities. But hypothetical questions asked in good faith are crucial building blocks of knowledge creation. Asking “What if we tried something else?” leads to the formation of a hypothesis, which is a theory or proposition that can be subjected to testing and experimentation.

This section has focused more on the types of genuinely interrogative questions that can lead to productive ideas for further exploration, research, and knowledge creation once you decide how you want to go public with your thinking. For more on using rhetorical and hypothetical questions as devices in your public writing, see Chapter 4 “Joining the Conversation”.

Key Takeaways

- At least two out of the following three elements are involved in critical inquiry: self, text, and context. When all three are involved, the richest questions arise.

- Expanding your notion of what constitutes a “text” will greatly enrich your possibilities for analysis and interpretation.

- Rhetorical or hypothetical questions, while often used in the public realm, can also perform a useful function in private, low-stakes writing, especially when they are genuinely interrogative and lead to further productive thinking.

Exercises

- Use the Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context to develop a researched essay topic on one of the following types of texts. Note that you are developing a topic at this point. Sketch out a plan for how you would go about finding answers to some of the questions requiring research.

- An editorial in the newspaper

- A website

- A blog

- A television show

- A music CD or video

- A film

- A video game

- A political candidate

- A building

- A painting or sculpture

- A feature of your college campus

- A short story or poem

- Perform a scavenger hunt in the world of advertising, politics, and/or education for the next week or so to compile a list of questions. (You could draw from the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts” in Chapter 2 “Becoming a Critical Reader” to find examples.) Label each question you find as rhetorical, hypothetical, or interrogative. If the questions are rhetorical or hypothetical, indicate whether they are still being asked in a genuinely interrogative way. Bring your examples to class for discussion or post them to your group’s or class’s discussion board.

- Apply the Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context to a key concept in an introductory course in which you are currently enrolled.

“Posing Productive Questions” by Saylor Academy is available in Handbook for Writers, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Generating Further Questions

Even after you have your core plan in place and start to do some initial research, you should still be very flexible with your plan and let your research and critical thinking guide you. You can help solidify your plan by continually and repeatedly asking questions at all stages of the writing process. Some possible questions follow:

- Am I following the assignment guidelines?

- Do these details actually support these ideas?

- Am I truly representing my intended position?

- What aspects of this topic have I not covered that would add positively to my paper?

- Is my core topic a solid choice?

- What organizational structure would best present my ideas?

- Is a first-person, second-person, or third-person essay the most powerful form to use for this topic?

- What can I do to make my ideas matter to my audience?

- Exactly what is my purpose in pursuing this topic?

- Do my key points directly address my purpose?

- Every time you make some adjustments to your topic, audience, purpose, or form, ask these same questions again until you stop adjusting and stop getting different answers to the questions.

Key Takeaways

- A writing plan is the first step in shaping a writing project. The next step is to adjust and shape the plan to make the best possible end product.

- A core method of adjusting a writing plan is to systematically ask and answer questions about the plan until you stop getting different answers.

- When asking questions to adjust a writing plan, ask about all aspects of the writing project, including questions about the topic, audience, purpose, form, and assignment guidelines.

Exercises

- Discuss how you would write a descriptive, informative essay for the following audiences on a subject in which you have a passionate interest:

- People who share your passion for and knowledge about the subject

- People who have a passing knowledge and limited interest in the subject

- People who know absolutely nothing about the subject and who might even be a little hostile toward it

- Discuss how would you approach writing a descriptive, informative essay on the following subjects for the third audience listed in question 1 (people who know absolutely nothing about the subject and who might even be a little hostile toward it):

- A violent video game

- A controversial celebrity or politician

- A reality television show

- Let’s say you have a specific topic and audience in mind, category (a) from questions 1 and 2: people who share your passion for and knowledge about violent video games. Discuss how your plan for an essay would change based on the following purposes:

- To persuade an audience that your favorite game is the best in its class

- To inform an audience about some of the cutting-edge methods for reaching new levels in the game

- To compare and contrast the features of the newest version of the game with previous versions

- To analyze why the game is so appealing to certain demographic profiles of the population

“Generating Further Questions” by Saylor Academy is available in Handbook for Writers, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

More Questions to Ask

The first phase of composing a strong piece of writing occurs in the pre-writing phase, and in WRIT, you’ll practice and learn how to plan your writing responses. Unlike a formal research essay assignment–where you’ll often have weeks to research, plan, and compose a polished final essay–in WRIT, your responses will be shorter and designed to be completed within a set period of time. The ability to respond in writing quickly is a core skill you’ll practice in WRIT; that skill is called time-on-task writing. While the pre-writing phase will be shorter, you should still learn to ask a few key questions about the prompt to help narrow down your overall writing goal.

- When reading a writing prompt, the following are helpful questions to ask and answer:

- What is the topic of the prompt?

- What is the main argument (thesis) the author makes?

- What is the purpose of the prompt? Why does the author want to convince you of her argumentative position?

- What kind of details or supporting points does the author provide?

- Do I agree or disagree with the author’s points? Why or why not?

- Can I provide reasons to oppose the author’s argument?

- Do I understand WHY I support or oppose the author’s argument?

By asking and answering these questions, you can jump-start your essay outline and formulate your own thesis. A good way to begin is to write a one-sentence response to each question. Whether you practice this skill in class or not, there are a number of ways that you can do so every day. You can:

- Read an opinion editorial on a news site

- Watch a film documentary

- Watch a television interview

- Listen to a documentary podcast

- Track a social media hashtag

Most of the media with which we engage daily come with thesis statements, points of view, arguments both well-supported and not-so-well supported: the more you bring critical thought–by applying the core questions from above–to these spaces, the more you’ll develop into a critical thinker who is ready to become a critical writer.

- “Posing Productive Questions” by Saylor Academy is available in Handbook for Writers, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

- “Generating Further Questions” by Saylor Academy is available in Handbook for Writers, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

- Excerpt from “What Are Writing Prompts” by Andrew M. Stracuzzi and Andre Cormier is available in Putting the Pieces Together, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0