Chapter 10: Lifespan Development

10.2 Developmental Theories

Learning Objectives

- Define Freud’s theory of psychosexual development

- Describe the major tasks of child and adult psychosocial development according to Erikson

- Give examples of behavior and key vocabulary in each of Piaget’s stages of cognitive development

- Describe Kohlberg’s theory of moral development and the stages of reasoning

- Explain the procedure, results, and implications of Hamlin and Wynn’s research on moral reasoning in infants

Psychosexual and Psychosocial Theories of Development

Psychosexual Theory of Development

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) believed that personality develops during early childhood. For Freud, childhood experiences shape our personalities and behavior as adults. Freud viewed development as discontinuous; he believed that each of us must pass through a serious of stages during childhood, and that if we lack proper nurturance and parenting during a stage, we may become stuck, or fixated, in that stage. Freud’s stages are called the stages of psychosexual development. According to Freud, children’s pleasure-seeking urges are focused on a different area of the body, called an erogenous zone, at each of the five stages of development: oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital.

While most of Freud’s ideas have not found support in modern research, we cannot discount the contributions that Freud has made to the field of psychology. Psychologists today dispute Freud’s psychosexual stages as a legitimate explanation for how one’s personality develops, but what we can take away from Freud’s theory is that personality is shaped, in some part, by experiences we have in childhood. These stages are discussed in detail in the module on personality.

Psychosocial Theory of Development

Erik Erikson (1902–1994) (Figure 1), another stage theorist, took Freud’s theory and modified it as psychosocial theory. Erikson’s psychosocial development theory emphasizes the social nature of our development rather than its sexual nature. While Freud believed that personality is shaped only in childhood, Erikson proposed that personality development takes place all through the lifespan. Erikson suggested that how we interact with others is what affects our sense of self, or what he called the ego identity.

Erikson proposed that we are motivated by a need to achieve competence in certain areas of our lives. According to psychosocial theory, we experience eight stages of development over our lifespan, from infancy through late adulthood. At each stage there is a conflict, or task, that we need to resolve. Successful completion of each developmental task results in a sense of competence and a healthy personality. Failure to master these tasks leads to feelings of inadequacy.

According to Erikson (1963), trust is the basis of our development during infancy (birth to 12 months). Therefore, the primary task of this stage is trust versus mistrust. Infants are dependent upon their caregivers, so caregivers who are responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust; their baby will see the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can engender feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust; their baby may see the world as unpredictable.

As toddlers (ages 1–3 years) begin to explore their world, they learn that they can control their actions and act on the environment to get results. They begin to show clear preferences for certain elements of the environment, such as food, toys, and clothing. A toddler’s main task is to resolve the issue of autonomy versus shame and doubt, by working to establish independence. This is the “me do it” stage. For example, we might observe a budding sense of autonomy in a 2-year-old child who wants to choose her clothes and dress herself. Although her outfits might not be appropriate for the situation, her input in such basic decisions has an effect on her sense of independence. If denied the opportunity to act on her environment, she may begin to doubt her abilities, which could lead to low self-esteem and feelings of shame.

Once children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they are capable of initiating activities and asserting control over their world through social interactions and play. According to Erikson, preschool children must resolve the task of initiative versus guilt. By learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others, preschool children can master this task. Those who do will develop self-confidence and feel a sense of purpose. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage—with their initiative misfiring or stifled—may develop feelings of guilt. How might over-controlling parents stifle a child’s initiative?

During the elementary school stage (ages 6–12), children face the task of industry versus inferiority. Children begin to compare themselves to their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate when they don’t measure up. What are some things parents and teachers can do to help children develop a sense of competence and a belief in themselves and their abilities?

In adolescence (ages 12–18), children face the task of identity versus role confusion. According to Erikson, an adolescent’s main task is developing a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, most adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit. Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. What happens to apathetic adolescents, who do not make a conscious search for identity, or those who are pressured to conform to their parents’ ideas for the future? These teens will have a weak sense of self and experience role confusion. They are unsure of their identity and confused about the future.

People in early adulthood (i.e., 20s through early 40s) are concerned with intimacy versus isolation. After we have developed a sense of self in adolescence, we are ready to share our life with others. Erikson said that we must have a strong sense of self before developing intimate relationships with others. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.

When people reach their 40s, they enter the time known as middle adulthood, which extends to the mid-60s. The social task of middle adulthood is generativity versus stagnation. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others, through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children. Those who do not master this task may experience stagnation, having little connection with others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.

From the mid-60s to the end of life, we are in the period of development known as late adulthood. Erikson’s task at this stage is called integrity versus despair. He said that people in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity, and they can look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” and “could have” been. They face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair. Table 1 summarizes the stages of Erikson’s theory.

| Stage | Age (years) | Developmental Task | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–1 | Trust vs. mistrust | Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

| 2 | 1–3 | Autonomy vs. shame/doubt | Develop a sense of independence in many tasks |

| 3 | 3–6 | Initiative vs. guilt | Take initiative on some activities—may develop guilt when unsuccessful or boundaries overstepped |

| 4 | 7–11 | Industry vs. inferiority | Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

| 5 | 12–18 | Identity vs. confusion | Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

| 6 | 19–29 | Intimacy vs. isolation | Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

| 7 | 30–64 | Generativity vs. stagnation | Contribute to society and be part of a family |

| 8 | 65– | Integrity vs. despair | Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions |

Cognitive Development

Cognitive Theory of Development

Jean Piaget (1896–1980) is another stage theorist who studied childhood development (Figure 1). Instead of approaching development from a psychoanalytical or psychosocial perspective, Piaget focused on children’s cognitive growth. He believed that thinking is a central aspect of development and that children are naturally inquisitive. However, he said that children do not think and reason like adults (Piaget, 1930, 1932). His theory of cognitive development holds that our cognitive abilities develop through specific stages, which exemplifies the discontinuity approach to development. As we progress to a new stage, there is a distinct shift in how we think and reason.

Piaget said that children develop schemata to help them understand the world. Schemata are concepts (mental models) that are used to help us categorize and interpret information. By the time children have reached adulthood, they have created schemata for almost everything. When children learn new information, they adjust their schemata through two processes: assimilation and accommodation. First, they assimilate new information or experiences in terms of their current schemata: assimilation is when they take in information that is comparable to what they already know. Accommodation describes when they change their schemata based on new information. This process continues as children interact with their environment.

For example, 2-year-old Blake learned the schema for dogs because his family has a Labrador retriever. When Blake sees other dogs in his picture books, he says, “Look mommy, dog!” Thus, he has assimilated them into his schema for dogs. One day, Blake sees a sheep for the first time and says, “Look mommy, dog!” Having a basic schema that a dog is an animal with four legs and fur, Blake thinks all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. When Blake’s mom tells him that the animal he sees is a sheep, not a dog, Blake must accommodate his schema for dogs to include more information based on his new experiences. Blake’s schema for dog was too broad, since not all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. He now modifies his schema for dogs and forms a new one for sheep.

Link to Learning

Watch this short video clip to review the concepts of schema, assimilation and accommodation.

Like Freud and Erikson, Piaget thought development unfolds in a series of stages approximately associated with age ranges. He proposed a theory of cognitive development that unfolds in four stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

| Age (years) | Stage | Description | Developmental issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 | Sensorimotor | World experienced through senses and actions | Object permanence Stranger anxiety |

| 2–6 | Preoperational | Use words and images to represent things, but lack logical reasoning | Pretend play Egocentrism Language development |

| 7–11 | Concrete operational | Understand concrete events and analogies logically; perform arithmetical operations | Conservation Mathematical transformations |

| 12– | Formal operational | Formal operations Utilize abstract reasoning |

Abstract logic Moral reasoning |

The first stage is the sensorimotor stage, which lasts from birth to about 2 years old. During this stage, children learn about the world through their senses and motor behavior. Young children put objects in their mouths to see if the items are edible, and once they can grasp objects, they may shake or bang them to see if they make sounds. Between 5 and 8 months old, the child develops object permanence, which is the understanding that even if something is out of sight, it still exists (Bogartz, Shinskey, & Schilling, 2000). According to Piaget, young infants do not remember an object after it has been removed from sight. Piaget studied infants’ reactions when a toy was first shown to an infant and then hidden under a blanket. Infants who had already developed object permanence would reach for the hidden toy, indicating that they knew it still existed, whereas infants who had not developed object permanence would appear confused.

Watch It

Please take a few minutes to view this brief video demonstrating different children’s ability to understand object permanence:

In Piaget’s view, around the same time children develop object permanence, they also begin to exhibit stranger anxiety, which is a fear of unfamiliar people. Babies may demonstrate this by crying and turning away from a stranger, by clinging to a caregiver, or by attempting to reach their arms toward familiar faces such as parents. Stranger anxiety results when a child is unable to assimilate the stranger into an existing schema; therefore, she can’t predict what her experience with that stranger will be like, which results in a fear response.

Piaget’s second stage is the preoperational stage, which is from approximately 2 to 7 years old. In this stage, children can use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage engage in pretend play. A child’s arms might become airplane wings as he zooms around the room, or a child with a stick might become a brave knight with a sword. Children also begin to use language in the preoperational stage, but they cannot understand adult logic or mentally manipulate information (the term operational refers to logical manipulation of information, so children at this stage are considered to be pre-operational). Children’s logic is based on their own personal knowledge of the world so far, rather than on conventional knowledge. For example, dad gave a slice of pizza to 10-year-old Keiko and another slice to her 3-year-old brother, Kenny. Kenny’s pizza slice was cut into five pieces, so Kenny told his sister that he got more pizza than she did. Children in this stage cannot perform mental operations because they have not developed an understanding of conservation, which is the idea that even if you change the appearance of something, it is still equal in size as long as nothing has been removed or added.

Watch It

This video shows a 4.5-year-old boy in the preoperational stage as he responds to Piaget’s conservation tasks.

You can view the transcript for “A typical child on Piaget’s conservation tasks” here (opens in new window).

During this stage, we also expect children to display egocentrism, which means that the child is not able to take the perspective of others. A child at this stage thinks that everyone sees, thinks, and feels just as they do. Let’s look at Kenny and Keiko again. Keiko’s birthday is coming up, so their mom takes Kenny to the toy store to choose a present for his sister. He selects an Iron Man action figure for her, thinking that if he likes the toy, his sister will too. An egocentric child is not able to infer the perspective of other people and instead attributes his own perspective. At some point during this stage and typically between 3 and 5 years old, children come to understand that people have thoughts, feelings, and beliefs that are different from their own. This is known as theory-of-mind (TOM).

Watch It

Piaget developed the Three-Mountain Task to determine the level of egocentrism displayed by children. Children view a 3-dimensional mountain scene from one viewpoint, and are asked what another person at a different viewpoint would see in the same scene. Watch the Three-Mountain Task in action in this short video from the University of Minnesota and the Science Museum of Minnesota.

You can view the transcript for “Piaget’s Mountains Task” here (opens in new window).

Piaget’s third stage is the concrete operational stage, which occurs from about 7 to 11 years old. In this stage, children can think logically about real (concrete) events; they have a firm grasp on the use of numbers and start to employ memory strategies. They can perform mathematical operations and understand transformations, such as addition is the opposite of subtraction, and multiplication is the opposite of division. In this stage, children also master the concept of conservation: Even if something changes shape, its mass, volume, and number stay the same. For example, if you pour water from a tall, thin glass to a short, fat glass, you still have the same amount of water. Remember Keiko and Kenny and the pizza? How did Keiko know that Kenny was wrong when he said that he had more pizza?

Children in the concrete operational stage also understand the principle of reversibility, which means that objects can be changed and then returned back to their original form or condition. Take, for example, water that you poured into the short, fat glass: You can pour water from the fat glass back to the thin glass and still have the same amount (minus a couple of drops).

The fourth, and last, stage in Piaget’s theory is the formal operational stage, which is from about age 11 to adulthood. Whereas children in the concrete operational stage are able to think logically only about concrete events, children in the formal operational stage can also deal with abstract ideas and hypothetical situations. Children in this stage can use abstract thinking to problem solve, look at alternative solutions, and test these solutions. In adolescence, a renewed egocentrism occurs. For example, a 15-year-old with a very small pimple on her face might think it is huge and incredibly visible, under the mistaken impression that others must share her perceptions.

Beyond Formal Operational Thought

As with other major contributors of theories of development, several of Piaget’s ideas have come under criticism based on the results of further research. For example, several contemporary studies support a model of development that is more continuous than Piaget’s discrete stages (Courage & Howe, 2002; Siegler, 2005, 2006). Many others suggest that children reach cognitive milestones earlier than Piaget describes (Baillargeon, 2004; de Hevia & Spelke, 2010).

According to Piaget, the highest level of cognitive development is formal operational thought, which develops between 11 and 20 years old. However, many developmental psychologists disagree with Piaget, suggesting a fifth stage of cognitive development, known as the postformal stage (Basseches, 1984; Commons & Bresette, 2006; Sinnott, 1998). In postformal thinking, decisions are made based on situations and circumstances, and logic is integrated with emotion as adults develop principles that depend on contexts. One way that we can see the difference between an adult in postformal thought and an adolescent in formal operations is in terms of how they handle emotionally charged issues.

It seems that once we reach adulthood our problem solving abilities change: As we attempt to solve problems, we tend to think more deeply about many areas of our lives, such as relationships, work, and politics (Labouvie-Vief & Diehl, 1999). Because of this, postformal thinkers are able to draw on past experiences to help them solve new problems. Problem-solving strategies using postformal thought vary, depending on the situation. What does this mean? Adults can recognize, for example, that what seems to be an ideal solution to a problem at work involving a disagreement with a colleague may not be the best solution to a disagreement with a significant other.

Think It Over

Explain how you would use your understanding of one of the major developmental theories (psychosexual, psychosocial, or cognitive) to deal with each of the difficulties listed below:

- Your infant daughter puts everything in her mouth, including the dog’s food.

- Your eight-year-old son is failing math; all he cares about is baseball.

- Your two-year-old daughter refuses to wear the clothes you pick for her every morning, which makes getting dressed a twenty-minute battle.

- Your sixty-eight-year-old neighbor is chronically depressed and feels she has wasted her life.

- Your 18-year-old daughter has decided not to go to college. Instead she’s moving to Colorado to become a ski instructor.

- Your 11-year-old son is the class bully.

Moral Development

Theory of Moral Development

A major task beginning in childhood and continuing into adolescence is discerning right from wrong. Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987) extended upon the foundation that Piaget built regarding cognitive development. Kohlberg believed that moral development, like cognitive development, follows a series of stages. To develop this theory, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to people of all ages, and then he analyzed their answers to find evidence of their particular stage of moral development. Before reading about the stages, take a minute to consider how you would answer one of Kohlberg’s best-known moral dilemmas, commonly known as the Heinz dilemma:

In Europe, a woman was near death from a special kind of cancer. There was one drug that the doctors thought might save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost him to make. He paid $200 for the radium and charged $2,000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about $1,000, which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said: “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So Heinz got desperate and broke into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Should the husband have done that? (Kohlberg, 1969, p. 379)

How would you answer this dilemma? Kohlberg was not interested in whether you answer yes or no to the dilemma: Instead, he was interested in the reasoning behind your answer.

After presenting people with this and various other moral dilemmas, Kohlberg reviewed people’s responses and placed them in different stages of moral reasoning (Figure 1). According to Kohlberg, an individual progresses from the capacity for pre-conventional morality (before age 9) to the capacity for conventional morality (early adolescence), and toward attaining post-conventional morality (once formal operational thought is attained), which only a few fully achieve. Kohlberg placed in the highest stage responses that reflected the reasoning that Heinz should steal the drug because his wife’s life is more important than the pharmacist making money. The value of a human life overrides the pharmacist’s greed.

It is important to realize that even those people who have the most sophisticated, post-conventional reasons for some choices may make other choices for the simplest of pre-conventional reasons. Many psychologists agree with Kohlberg’s theory of moral development but point out that moral reasoning is very different from moral behavior. Sometimes what we say we would do in a situation is not what we actually do in that situation. In other words, we might “talk the talk,” but not “walk the walk.”

How does this theory apply to males and females? Kohlberg (1969) felt that more males than females move past stage four in their moral development. He went on to note that women seem to be deficient in their moral reasoning abilities. These ideas were not well received by Carol Gilligan, a research assistant of Kohlberg, who consequently developed her own ideas of moral development. In her groundbreaking book, In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development, Gilligan (1982) criticized her former mentor’s theory because it was based only on upper class white men and boys. She argued that women are not deficient in their moral reasoning—she proposed that males and females reason differently. Girls and women focus more on staying connected and the importance of interpersonal relationships. Therefore, in the Heinz dilemma, many girls and women respond that Heinz should not steal the medicine. Their reasoning is that if he steals the medicine, is arrested, and is put in jail, then he and his wife will be separated, and she could die while he is still in prison.

Psych in Real Life: Moral Reasoning

Moral Reasoning in Infants

The work of Lawrence Kohlberg was an important start to modern research on moral development and reasoning. However, Kohlberg relied on a specific method: he presented moral dilemmas (like the Heinz problem) and asked children and adults to explain what they would do and—more importantly—why they would act in that particular way. Kohlberg found that children tended to make choices based on avoiding punishment and gaining praise. But children are at a disadvantage compared to adults when they must rely on language to convey their inner thoughts and emotional reactions, so what they say may not adequately capture the complexity of their thinking.

Starting in the 1980s, developmental psychologists created new methods for studying the thought processes of children, even of infants long before they acquire language. One particularly effective method is to present children with puppet shows, which grab their attention, and then record nonverbal behaviors, such as looking and choosing, to identify children’s preferences or interests.

A research group at Yale University has been using the puppet show technique to study moral thinking of children for much of the past decade. What they have discovered has given us a glimpse of surprisingly complex thought processes that may serve as the foundation of moral reasoning.

EXPERIMENT 1: Do children prefer givers or takers?

In 2011, J. Kiley Hamlin and Karen Wynn put on puppet shows for very young children: 5-month-old infants. The infants watch a puppet bouncing a ball. We’ll call this puppet the “bouncer puppet.” Two other puppets stand at the back of the stage, one to left and the other to the right. After a few bounces, the ball gets away from the bouncer puppet and rolls to the side of the stage toward one of the other puppets. This puppet grabs the ball. The bouncer puppet turns toward the ball and opens its arms, as if asking for the ball back.

This is where the puppet show gets interesting (for a young infant, anyway!). Sometimes, the puppet with the ball rolls it back to the bouncer puppet. This is the “giver puppet” condition. Other times, the infant sees a different ending. As the bouncer puppet opens its arms to ask for the ball, the puppet with the ball turns and runs away with it. This is the “taker puppet” condition. Although the giver and taker puppets are two copies of the same animal doll, they are easily distinguished because they are wearing different colored shirts, and color is a quality that infants easily distinguish and remember.

Watch It

The bouncer puppet and taker puppet video looks like this:

Text alternative for the bouncer puppet and taker puppet video available here (opens in new window).

Each infant sees both conditions: the giver condition and the taker condition. Just after the end of the second puppet show (i.e., the second condition), a new researcher, who doesn’t know which puppet was the giver and which was the taker, sits in front of the infant with the giver puppet in one hand and the taker puppet in the other. The 5-month-old infants are allowed to reach for a puppet. The one the child reaches out to touch is considered the preferred puppet.

Remember that Lawrence Kohlberg thought that children at this age—and, in fact, through 9 years of age—are primarily motivated to avoid punishment and seek rewards. Neither Kohlberg nor Carol Gilligan nor Jean Piaget was likely to predict that infants would develop preferences based on the type of behavior shown by other individuals.

Work It Out

The puppet show is over and the experimenter is holding the two dolls—the giver puppet and the taker puppet—in front of the infant. The reaching behavior of the infant is being videotaped for later analysis.

What do you think? Make a prediction about the results of this study—which should reflect your own “theory” of children’s ability to judge and care about the types of behavior others display. Do you think infants will choose the taker or the giver puppet? Do you expect the results to be significant?

INSTRUCTIONS: Adjust the pink bar on the left to show the percentage of infants who reached for the giver puppet. The yellow bar on the right will automatically adjust to make the total (sum of both bars) equal 100%.

Show Answer

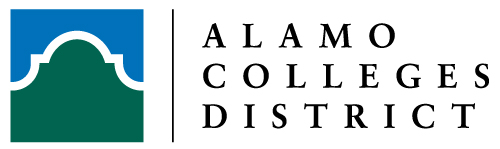

Here are the results from Experiment 1:

Experiment 1 suggests that these 5-month-old infants are not just passive observers in the world. They notice what others do and, if we are interpreting the results of experiments like this one correctly, they distinguish helpful behaviors (“prosocial behaviors”) from behaviors that hurt others (“antisocial behaviors”). But they do more that that. They are attracted to those who are acting in a prosocial way, and they reject those who act in an antisocial way.

These researchers also tested infants who were only 3-months old. These infants were so immature that they did not yet have good control of their arms, so the experimenter could not use “reaching for one of the puppets” as the dependent variable, as they did with the 5-month-olds. Three-month-old infants can control where they look quite well, and previous research has indicated that very young infants will look longer at objects they want. The researchers showed these very young infants the same puppet shows that were described above and then, during the choice phase, they recorded which puppet (giver or taker) the 3-month-olds looked at longer. The results were very similar to those found with the 5-month-olds. A strong majority of younger infants (92%) looked longer at the giver puppet than the taker puppet.

But this isn’t the end of the story…

EXPERIMENT 2: Do infants judge others based on their behavior?

In the research world, the early attempts to study something, when the researchers work to develop a solid and reliable research procedure, is often the most challenging time. Once the researcher works through initial problems and issues and begins to get consistent results, he or she can gain a deeper understanding by adding new variables or testing different groups of subjects (e.g., older children or children with some interesting psychological characteristics).

The study you just read about is an example of a simple, basic study. The researchers found that infants preferred puppets that help another puppet (the puppet in the giver condition) over puppets that are not nice to another puppet (the puppet in the taker condition). A common sense interpretation of this simple result is that infants like nice behavior and they dislike hurtful behavior. And perhaps that is as complicated as an 8-month-old infant’s thoughts can be. But maybe not.

Dr. Hamlin and her colleagues wondered if infants might consider more factors when judging an event. Adults generally prefer situations where good things happen to someone rather than something harmful. However, when adults see someone do something bad, they may find satisfaction in seeing that person punished by having something bad happen to him or her. In a nutshell: good things should happen to good people and bad things should happen to bad people. This is what is called “just world” thinking, where people get what they deserve.

In the study we will call Experiment 2, Hamlin’s team tested 8-month-old infants and repeated the procedures from Experiment 1 with a major addition. In Experiment 1 (described above), the puppet bouncing the ball was a neutral character, neither good nor bad. In Experiment 2, the infants saw 2 different shows. First, they saw the bouncer puppet either helping or hindering another puppet. Then, they watched the same ball-bouncing puppet show. Here is what happened:

- Puppet Show #1: A puppet is trying to open a box, but cannot quite succeed. Two puppets stand in the background. For some infants, as the first puppet struggles to open the box, one of the puppets in the back comes forward and helps to open the box. This is the helper puppet. For other children, as the first puppet struggles, a puppet comes from the back and jumps on the box, slamming it shut. This is the hinderer puppet. Each infant sees only a helper or a hinderer—not both.

Watch It

Here is a video showing the helper puppet situation:

Text alternative for helper puppet video available here (opens in new window).

- Puppet Show #2: Just after the infants have watched the first show, the second puppet show begins. This is the show that you read about in Experiment 1. The only thing that is new is that the bouncer puppet, the one that loses the ball, is either the helper puppet from Puppet Show #1 or the hinderer puppet from Puppet Show #1. Each infant sees this puppet lose the ball to a giver, who returns the ball, and to a taker, who runs off with the ball.

Watch It

This video demonstrates show #2. The elephant in the yellow shirt from the first show is now bouncing a ball. After dropping the ball, the moose in the green shirt gives it back to him, while the moose in the red shirt takes it away.

So far we have concluded that even young babies prefer the “nice” puppet and show a preference for a puppet who helps another puppet. But this only happened when the bouncer puppet was the Helper from the first puppet show. What if, instead of the nice elephant in the yellow shirt bouncing the ball, the elephant in the red shirt (the one who jumped on the duck’s box, remember?) was the one bouncing the ball? Imagine the same scenario: the mean elephant in red shirt is bouncing the ball, he drops it, and the moose in the green shirt gives it to him or the moose in the red shirt takes it away.

So now things are getting interesting, right? Do 8-month old infants understand the concepts of revenge or justice? We must always be careful when labeling behaviors of children (or animals) with characteristics we use for human adults. In the description above, we have talked of “nice puppets” and “mean puppets” and used other loaded terms. It is tempting to interpret the choices of the 8-month-olds as a kind of revenge motive: the bad guy gets its just desserts (the hinderer puppet has its ball stolen) and the good guy gets its just reward (the helper puppet is itself helped by the giver). Maybe that is what is going on, but we encourage you to consider these very sophisticated types of thinking as merely one hypothesis. Remember the facts—what did the puppets do and what choices did the infants make?—without committing yourself to the adult-level interpretation.

The researchers believe that this type of thinking, which is remarkably sophisticated, takes some cognitive development. They tested 5-month-olds using the same procedures, and the results with these younger infants was different. The 5-month-olds showed an overwhelming preference for the giver puppets, regardless of who was bouncing the ball. Maybe it is too complex for them to understand that the bouncer puppet in the second show was the same puppet from the first show, Or perhaps their memory processes are too fragile to hold onto information for that length of time. Possibly the “revenge” motive is too advanced a way of thinking. Or maybe something else is going on. What is clear is that 5-month-olds and 8-month-olds respond differently to the situations tested in the second experiment.

EXPERIMENT 3: Do infants judge others based on their preferences?

Across the first two experiments, infants appear to prefer puppets (and, by extension, maybe people, as well) that are helpful over those that are not helpful. Experiment 2 complicated our story a bit, but it still appears that prosocial behavior is attractive to infants and antisocial behavior is unattractive. But another experiment, again using the bouncing ball show, suggests that infants as young as 8-months of age may have some other motives that are less altruistic than the first two experiments indicate.

In a study by Hamlin, Mahanjan, Liberman, and Wynn from 2013, 9-month-old infants watched the bouncing ball show, but with a new twist.

At the beginning of the experiment—Phase 1—the infants were given a choice between graham crackers and green beans. The experimenters determined which food the infant preferred.

Watch It

This video shows an infant choosing between graham crackers or green beans.

You can view the transcript for “Graham Cracker Choice” here (opens in new window).

Then, in Phase 2, the infants watched a puppet make the same choice. For half of the infants, the puppet chose the same food that they preferred, saying “Mmmm, yum! I like ___(graham crackers or green beans)!” and saying “Eww, yuck! I don’t like _____ (graham crackers or green beans!” This was called the SIMILAR condition, because the puppet was similar to the child in its food preference. For the other half of the infants, the puppet chose the other food, choosing graham crackers if the infant preferred green beans and preferring green beans if the infant liked graham crackers. This was the DISSIMILAR condition.

Watch It

This video shows Phase 2 of the experiment, in which the animals chose either a similar or dissimilar preferred food as the infant.

You can view the transcript for “Similar / Dissimilar Puppet Preference Example” here (opens in new window).

Why did experimenters do this? They wanted to know if young children form in-groups and out-groups by perceiving some people as being like them and other people as being unlike them. The experimenters noted in their research introduction that we (adults) are influenced by our perception that others are similar to us or not like us. We tend to project positive qualities—being trustworthy, intelligent, kind—on people we perceive as similar to ourselves, and people we see as unlike us are seen as having negative qualities—being relatively untrustworthy, unintelligent, and unkind.[1]

Of course, there is a big difference between claiming that adults use similarity to make judgments about others and saying that infants less than a year of age do the same thing. However, the researchers note that some recent research has suggested that infants less than a year old are more likely to develop peer friendships with other infants who “share their own food, clothing or toy preferences” compared to those who don’t.

So, back to the experiment. In Phase 3, the infants either saw a similar puppet (one that chose the food the baby preferred) or a dissimilar puppet (one that chose the food the baby did not prefer) bouncing the ball. As in the other experiments, the ball got away from the bouncer and rolled to the back of the stage. In one instance, the giver puppet returned the ball and, in the other instance, the other puppet ran away with the ball. Finally, in Phase 4, the 9-month-old baby was shown the giver and taker puppet and the experimenters recorded which of the two puppets the baby preferred (reached out to touch). This video shows the dog in the light blue shirt giving the ball back to the red bunny that preferred graham crackers.

Watch It

This video shows the dog in the light blue shirt giving the ball back to the red bunny that preferred graham crackers.

Here is a summary of the four phases in Experiment 3:

- Phase 1: The infant chooses graham crackers or green beans.

- Phase 2: The bouncer puppets chooses graham crackers or green beans.

- Similar condition: The bouncer chooses the same food that the infant chose.

- Dissimilar condition: The bouncer chooses the food that the infant did not choose.

- Phase 3: This is the same bouncing ball experiment that you have been reading about.

- Remember that each child sees both the Giver and Taker shows.

- Phase 4: This is the same choice—Giver or Taker—that was the final phase in the other two experiments

Work It Out

Now make predictions for the results. Here is a matrix picture of the design of the experiment:

INSTRUCTIONS: Adjust bars A and C to make your predictions. Bar A represents the “nice” puppet who gave the ball to the bouncer puppet that liked the same food as the child, while bar B represents the “mean” puppet who took the ball away from the bouncer puppet who liked the same food as the child. Bar C represents the “nice” puppet who gave the ball back to the puppet who did not like the same food as the child, and bar D represents the puppet who took the ball away from the puppet who did not like the same food.

As before, move the bars on the left to indicate the percentage of infants preferring the giver puppet in the similar condition (purple bars) and in the dissimilar condition (green bars). The bars on the right will adjust to make the total in each of the similarity conditions equal 100%.

After you have recorded your predictions, click the “Show Answer” link to see the results from the experiment.

Show Answer

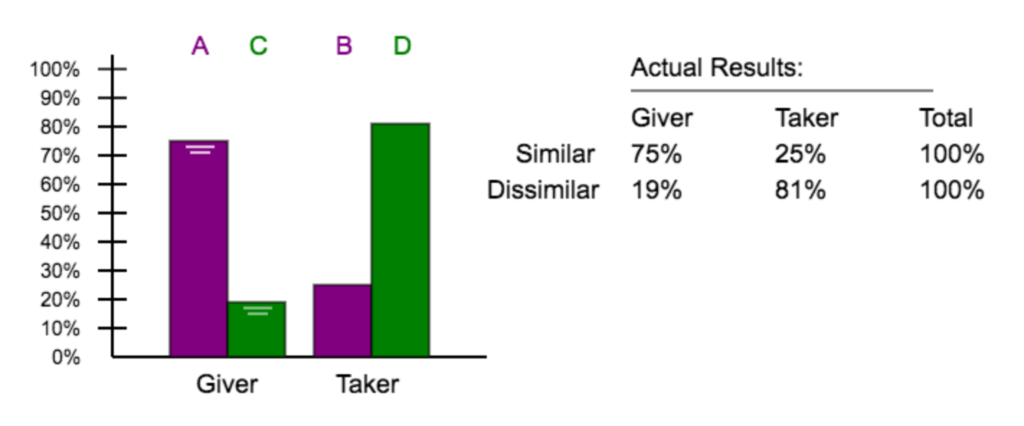

Here are the results from Experiment 3:

These results are similar to those for the 8-month-olds in the previous experiment. But remember that, in this experiment, the variable that distinguishes the two bouncer puppets was a food choice, not the prosocial or antisocial behavior in Experiment 2. If we take the results from Experiments 2 and 3 together, the results here suggest that the similar puppet is being treated as if it is nice or good. Puppets that treat this similar puppet in a nice way are preferred. Conversely, the dissimilar puppets are treated as if they have done something negative and puppets that treat these dissimilar puppets badly are preferred.

The experimenters also tested an older group of babies that were 14-months-old. The results for these older babies were consistent with the 9-month-old and, if anything, the effects were stronger. Their results showed that all infants preferred when the giver puppet was nice to the puppet that was similar to them and all infants preferred when puppets were mean to the puppet that was dissimilar to them.

CONCLUSIONS

This exercise started with a reminder that Lawrence Kohlberg found that children went through a long developmental process in their moral reasoning. Based on children’s reasoning aloud about moral dilemmas, Kohlberg concluded that children younger than about 8 or 9 years of age make moral decisions based on avoiding punishment and receiving praise. Neither his research nor that of most others in the 1970s and 1980s suggested that young children would use multiple sources of information and judgments about the meaning of behaviors in their thinking what sorts of behaviors are better or worse.

If Dr. Hamlin and her colleagues are right, then infants are much more sophisticated and complex in their thinking about the world than these earlier researchers thought. In Dr. Hamlin’s view, infants like good things to happen to good puppets and people, and bad things to happen to bad puppets and people. Experiment 3 suggests that they make judgments about more than helping and harming behavior. They prefer others who are like them (green beans vs. graham crackers) and they don’t mind if others who are not like them have unpleasant experiences.

The research we have been reviewing is just part of an impressive set of research on infant thinking. The ideas that the researchers have developed are intriguing and they are consistent with the modern view of the infant as an active, creative thinker. At the same time, remember that science doesn’t rest on an early set of explanations based on a small set of complicated experiments. Science pushed beyond what we currently know and believe. This starts with curiosity on your part. Are the experimenters correct in interpreting reaching behavior as showing a preference or is something else going on? Do infants really prefer prosocial behaviors to antisocial behaviors, or is there some other explanation for their preferences? How else could we test moral judgments of infants without using puppet shows? The next generation of creative scientists will push beyond what we know now, with new research methods and new ideas about the mind.

We’ll give Dr. Hamlin the last word. Here is part of her conclusion section from an article that summarizes some of the research we have been studying: “In sum, recent developmental research supports the claim that at least some aspects of human morality are innate…Indeed, these early tendencies are far from shallow, mechanical predispositions to behave well or knee-jerk reactions to particular states of the world. Infant moral inclinations are sophisticated, flexible, and surprisingly consistent with adults’ moral inclinations, incorporating aspects of moral goodness, evaluation, and retaliation. “ [Hamlin, 2013, p. 191]

Licenses and Attributions (Click to expand)

CC licensed content, Original

- Modification and adaptation, addition of video link. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Psychology in Real Life: Moral Reasoning. Authored by: Patrick Carroll for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Similar/Dissimilar Puppet Preference Example. Provided by: UBCHamlinLab . Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aT4ljlQw-Io. License: All Rights Reserved

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Psychology. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/9-2-lifespan-theories. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Picture of baby. Authored by: adtkedia . Located at: https://pixabay.com/p-1709003/?no_redirect. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

CC licensed content, Specific attribution

- Lifespan Theories. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/9-2-lifespan-theories. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

All rights reserved content

- Piaget – Stage 1 – Sensorimotor stage : Object Permanence. Authored by: Geert Stienissen. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NCdLNuP7OA8. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- A typical child on Piaget’s conservation tasks. Authored by: munakatay. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gnArvcWaH6I. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Piaget’s Mountains Task. Authored by: UofMNCYFC. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v4oYOjVDgo0. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Videos shared with permission from Kiley Hamlin. Provided by: The University of British Columbia: Vancouver Campus. Located at: http://cic.psych.ubc.ca/media-videos/. License: All Rights Reserved

- Babies want bad behavior punished video. Authored by: Kiley Hamlin. Provided by: Live Science. Located at: http://www.livescience.com/17205-babies-bad-behavior-punished.html. License: All Rights Reserved

- Graham Cracker Choice. Provided by: UBCHamlinLab. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VY005Pia4uA. License: All Rights Reserved

- Nice Blue Dog. Provided by: UBCHamlinLab . Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ijiru5ggPVQ. License: All Rights Reserved

- The experimenters support these claims by citing the following studies: (1) DeBruine, L.M. Facial resemblance enhances trust: Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 2002, 269: 1307-1312. (2) Brewer, M.B. In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 1979, 86: 307-324. (3) Doise, W., Cspely, G., Dann, and others. An experimental investigation into the formation of intergroup representation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1972, 2: 202-204. ↵

process proposed by Freud in which pleasure-seeking urges focus on different erogenous zones of the body as humans move through five stages of life

process proposed by Erikson in which social tasks are mastered as humans move through eight stages of life from infancy to adulthood

(plural = schemata) concept (mental model) that is used to help us categorize and interpret information

adjustment of a schema by adding information similar to what is already known

adjustment of a schema by changing a scheme to accommodate new information different from what was already known

first stage in Piaget’s theory of cognitive development; from birth through age 2, a child learns about the world through senses and motor behavior

idea that even if something is out of sight, it still exists

second stage in Piaget’s theory of cognitive development; from ages 2 to 7, children learn to use symbols and language but do not understand mental operations and often think illogically

idea that even if you change the appearance of something, it is still equal in size, volume, or number as long as nothing is added or removed

preoperational child’s difficulty in taking the perspective of others

the understanding that people have thoughts, feelings, and beliefs that are different from our own

third stage in Piaget’s theory of cognitive development; from about 7 to 11 years old, children can think logically about real (concrete) events

understanding that objects can be changed and then returned back to their original form or condition

final stage in Piaget’s theory of cognitive development; from age 11 and up, children are able to deal with abstract ideas and hypothetical situations

process proposed by Kohlberg; humans move through three stages of moral development