Chapter 13: Emotion and Motivation

13.1 Foundations of Motivation

Learning Objectives

- Illustrate intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

- Describe basic theories of motivation, including concepts such as instincts, drive reduction, and self-efficacy

- Explain the basic concepts associated with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

- Explain how different praise and mindsets can lead to different levels of performance

Why It Matters: Emotion and Motivation

What makes us behave as we do? What drives us to eat? What drives us toward sex? Is there a biological basis to explain the feelings we experience? How universal are emotions?

In this module, we will explore issues relating to both motivation and emotion. We will begin with a discussion of several theories that have been proposed to explain motivation and why we engage in a given behavior. You will learn about the physiological needs that drive some human behaviors, as well as the importance of our social experiences in influencing our actions.

Next, we will consider both eating and having sex as examples of motivated behaviors. What are the physiological mechanisms of hunger and satiety? What understanding do scientists have of why obesity occurs, and what treatments exist for obesity and eating disorders? How has research into human sex and sexuality evolved over the past century? How do psychologists understand and study the human experience of sexual orientation and gender identity? These questions—and more—will be explored.

This module will close with a discussion of emotion. You will learn about several theories that have been proposed to explain how emotion occurs, the biological underpinnings of emotion, and the universality of emotions.

Introduction to Motivation

Motivation to engage in a given behavior can come from internal and/or external factors. There are multiple theories have been put forward regarding motivation—biologically oriented theories that say the need to maintain bodily homeostasis motivates behavior, Bandura’s idea that our sense of self-efficacy motivates behavior, and others that focus on social aspects of motivation. In this section, you’ll learn about these theories as well as the famous work of Abraham Maslow and his hierarchy of needs.

Motivation

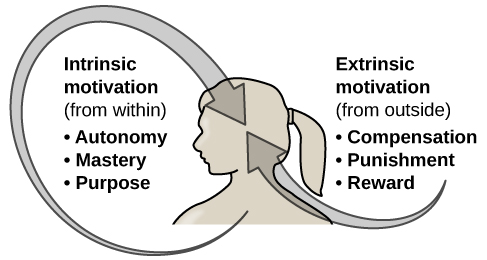

Why do we do the things we do? What motivations underlie our behaviors? Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal. In addition to biological motives, motivations can be intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors) (Figure 1). Intrinsically motivated behaviors are performed because of the sense of personal satisfaction that they bring, while extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed in order to receive something from others.

Think about why you are currently in college. Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature.

In reality, our motivations are often a mix of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but the nature of the mix of these factors might change over time (often in ways that seem counter-intuitive). There is an old adage: “Choose a job that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life,” meaning that if you enjoy your occupation, work doesn’t seem like . . . well, work. Some research suggests that this isn’t necessarily the case (Daniel & Esser, 1980; Deci, 1972; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). According to this research, receiving some sort of extrinsic reinforcement (i.e., getting paid) for engaging in behaviors that we enjoy leads to those behaviors being thought of as work no longer providing that same enjoyment. As a result, we might spend less time engaging in these reclassified behaviors in the absence of any extrinsic reinforcement. For example, Odessa loves baking, so in her free time, she bakes for fun. Oftentimes, after stocking shelves at her grocery store job, she often whips up pastries in the evenings because she enjoys baking. When a coworker in the store’s bakery department leaves his job, Odessa applies for his position and gets transferred to the bakery department. Although she enjoys what she does in her new job, after a few months, she no longer has much desire to concoct tasty treats in her free time. Baking has become work in a way that changes her motivation to do it (Figure 2). What Odessa has experienced is called the overjustification effect—intrinsic motivation is diminished when extrinsic motivation is given. This can lead to extinguishing the intrinsic motivation and creating a dependence on extrinsic rewards for continued performance (Deci et al., 1999).

Other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation may not be so vulnerable to the effects of extrinsic reinforcements, and in fact, reinforcements such as verbal praise might actually increase intrinsic motivation (Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994). In that case, Odessa’s motivation to bake in her free time might remain high if, for example, customers regularly compliment her baking or cake decorating skills.

These apparent discrepancies in the researchers’ findings may be understood by considering several factors. For one, physical reinforcement (such as money) and verbal reinforcement (such as praise) may affect an individual in very different ways. In fact, tangible rewards (i.e., money) tend to have more negative effects on intrinsic motivation than do intangible rewards (i.e., praise). Furthermore, the expectation of the extrinsic motivator by an individual is crucial: If the person expects to receive an extrinsic reward, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to be reduced. If, however, there is no such expectation, and the extrinsic motivation is presented as a surprise, then intrinsic motivation for the task tends to persist (Deci et al., 1999).

In educational settings, students are more likely to experience intrinsic motivation to learn when they feel a sense of belonging and respect in the classroom. This internalization can be enhanced if the evaluative aspects of the classroom are de-emphasized and if students feel that they exercise some control over the learning environment. Furthermore, providing students with activities that are challenging, yet doable, along with a rationale for engaging in various learning activities can enhance intrinsic motivation for those tasks (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Consider Hakim, a first-year law student with two courses this semester: Family Law and Criminal Law. The Family Law professor has a rather intimidating classroom: He likes to put students on the spot with tough questions, which often leaves students feeling belittled or embarrassed. Grades are based exclusively on quizzes and exams, and the instructor posts results of each test on the classroom door. In contrast, the Criminal Law professor facilitates classroom discussions and respectful debates in small groups. The majority of the course grade is not exam-based, but centers on a student-designed research project on a crime issue of the student’s choice. Research suggests that Hakim will be less intrinsically motivated in his Family Law course, where students are intimidated in the classroom setting, and there is an emphasis on teacher-driven evaluations. Hakim is likely to experience a higher level of intrinsic motivation in his Criminal Law course, where the class setting encourages inclusive collaboration and a respect for ideas, and where students have more influence over their learning activities.

Theories About Motivation

Another early theory of motivation proposed that the maintenance of homeostasis is particularly important in directing behavior. You may recall from your earlier reading that homeostasis is the tendency to maintain a balance, or optimal level, within a biological system. In a body system, a control center (which is often part of the brain) receives input from receptors (which are often complexes of neurons). The control center directs effectors (which may be other neurons) to correct any imbalance detected by the control center.

According to the drive theory of motivation, deviations from homeostasis create physiological needs. These needs result in psychological drive states that direct behavior to meet the need and, ultimately, bring the system back to homeostasis. For example, if it’s been a while since you ate, your blood sugar levels will drop below normal. This low blood sugar will induce a physiological need and a corresponding drive state (i.e., hunger) that will direct you to seek out and consume food (Figure 2). Eating will eliminate the hunger, and, ultimately, your blood sugar levels will return to normal. Interestingly, drive theory also emphasizes the role that habits play in the type of behavioral response in which we engage. A habit is a pattern of behavior in which we regularly engage. Once we have engaged in a behavior that successfully reduces a drive, we are more likely to engage in that behavior whenever faced with that drive in the future (Graham & Weiner, 1996).

Extensions of drive theory take into account levels of arousal as potential motivators. Just as drive theory aims to return the body to homeostasis, arousal theory aims to find the optimal level of arousal. If we are underaroused, we become bored and will seek out some sort of stimulation. On the other hand, if we are overaroused, we will engage in behaviors to reduce our arousal (Berlyne, 1960). Most students have experienced this need to maintain optimal levels of arousal over the course of their academic career. Think about how much stress students experience toward the end of spring semester. They feel overwhelmed with seemingly endless exams, papers, and major assignments that must be completed on time. They probably yearn for the rest and relaxation that awaits them over the extended summer break. However, once they finish the semester, it doesn’t take too long before they begin to feel bored. Generally, by the time the next semester is beginning in the fall, many students are quite happy to return to school. This is an example of how arousal theory works.

So what is the optimal level of arousal? What level leads to the best performance? Research shows that moderate arousal is generally best; when arousal is very high or very low, performance tends to suffer (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). Think of your arousal level regarding taking an exam for this class. If your level is very low, such as boredom and apathy, your performance will likely suffer. Similarly, a very high level, such as extreme anxiety, can be paralyzing and hinder performance. Consider the example of a softball team facing a tournament. They are favored to win their first game by a large margin, so they go into the game with a lower level of arousal and get beat by a less skilled team.

But optimal arousal level is more complex than a simple answer that the middle level is always best. Researchers Robert Yerkes (pronounced “Yerk-EES”) and John Dodson discovered that the optimal arousal level depends on the complexity and difficulty of the task to be performed (Figure 4). This relationship is known as Yerkes-Dodson law, which holds that a simple task is performed best when arousal levels are relatively high and complex tasks are best performed when arousal levels are lower.

Self-efficacy and Social Motives

Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in her own capability to complete a task, which may include a previous successful completion of the exact task or a similar task. Albert Bandura (1994) theorized that an individual’s sense of self-efficacy plays a pivotal role in motivating behavior. Bandura argues that motivation derives from expectations that we have about the consequences of our behaviors, and ultimately, it is the appreciation of our capacity to engage in a given behavior that will determine what we do and the future goals that we set for ourselves. For example, if you have a sincere belief in your ability to achieve at the highest level, you are more likely to take on challenging tasks and to not let setbacks dissuade you from seeing the task through to the end.

A number of theorists have focused their research on understanding social motives (McAdams & Constantian, 1983; McClelland & Liberman, 1949; Murray et al., 1938). Among the motives they describe are needs for achievement, affiliation, and intimacy. It is the need for achievement that drives accomplishment and performance. The need for affiliation encourages positive interactions with others, and the need for intimacy causes us to seek deep, meaningful relationships. Henry Murray et al. (1938) categorized these needs into domains. For example, the need for achievement and recognition falls under the domain of ambition. Dominance and aggression were recognized as needs under the domain of human power, and play was a recognized need in the domain of interpersonal affection.

Link to Learning

Watch this video from Dan Pink’s Ted talk on “The surprising truth about what motivates us.” Think about what things motivate you, and how you anticipate that you might respond to the types of incentives explained in the talk.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

While the theories of motivation described earlier relate to basic biological drives, individual characteristics, or social contexts, Abraham Maslow (1943) proposed a hierarchy of needs that spans the spectrum of motives ranging from the biological to the individual to the social. These needs are often depicted as a pyramid (Figure 1).

At the base of the pyramid are all of the physiological needs that are necessary for survival. These are followed by basic needs for security and safety, the need to be loved and to have a sense of belonging, and the need to have self-worth and confidence. The top tier of the pyramid is self-actualization, which is a need that essentially equates to achieving one’s full potential, and it can only be realized when needs lower on the pyramid have been met. To Maslow and humanistic theorists, self-actualization reflects the humanistic emphasis on positive aspects of human nature. Maslow suggested that this is an ongoing, life-long process and that only a small percentage of people actually achieve a self-actualized state (Francis & Kritsonis, 2006; Maslow, 1943).

According to Maslow (1943), one must satisfy lower-level needs before addressing those needs that occur higher in the pyramid. So, for example, if someone is struggling to find enough food to meet his nutritional requirements, it is quite unlikely that he would spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about whether others viewed him as a good person or not. Instead, all of his energies would be geared toward finding something to eat. However, it should be pointed out that Maslow’s theory has been criticized for its subjective nature and its inability to account for phenomena that occur in the real world (Leonard, 1982). Other research has more recently addressed that late in life, Maslow proposed a self-transcendence level above self-actualization—to represent striving for meaning and purpose beyond the concerns of oneself (Koltko-Rivera, 2006). For example, people sometimes make self-sacrifices in order to make a political statement or in an attempt to improve the conditions of others. Mohandas K. Gandhi, a world-renowned advocate for independence through nonviolent protest, on several occasions went on hunger strikes to protest a particular situation. People may starve themselves or otherwise put themselves in danger displaying higher-level motives beyond their own needs.

Link to Learning

Practice applying six real-life situations to a need taking precedence and a need is being sacrificed in this Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Exercise. To advance the screen, click on the “Next” link found on the bottom right of the video.

Review Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as well as the other theories of motivation in this Crash Course: The Power of Motivation video.

Think It Over

- Can you think of recent examples of how Maslow’s hierarchy of needs might have affected your behavior in some way?

Psych in Real Life: Growth Mindsets

How Mindset Influences Performance

Imagine that you are a parent and your child has just brought home a report card from 4th grade that is really good. You look it over and feel proud of your son or daughter. With a wide grin on your face, you turn to your child and say:

“I’m so proud of you! This report card is great! You __________”

- are so smart!

- must have worked so hard!

- have some jelly on your nose!

We hope you didn’t choose the jelly statement. Between the other two options, which one would you be more likely to blurt out?

It turns out that your choice could matter.

Carol Dweck, who is now a Professor of Psychology at Stanford University, has been studying factors that promote or interfere with achievement since the 1970s. Over this time, and especially since the mid-1990s, she came to realize that our ways of dealing with the world and particularly our behaviors in trying to achieve our own goals are influenced by what she calls “self-theories”: beliefs we have about our own abilities, strengths and weaknesses, and potential. These self-theories affect decisions we make about what is possible or sensible or reasonable to do in order to achieve our goals.

Before we discuss Carol Dweck’s work, please answer a few questions about your own beliefs. Try to answer based on your real ways of thinking. The questions are a bit repetitive, but answer each one without regard to your previous answers.

Take the 8-question Mindset Quiz here

Dr. Dweck and her colleagues have used questions like the ones you just answered to sort people into groups based on their beliefs about intelligence (and other abilities and skills). She has found that people tend to adopt one of two general set of beliefs about intelligence. People with a fixed mindset tend to think of intelligence as an “entity”—something that is part of a person’s essential self. According to people with this belief, intelligence does not change much regardless of what we do or what we experience. Other people have a growth mindset, and they tend to think of intelligence as being “incremental”—a quality that can change for better or worse depending on what we do and on the experiences we have. Some people are strongly committed to one or the other end of the fixed vs. growth mindset scale, while others fall in-between to varying degrees.

Study 1: Mueller & Dweck (1998)

If Prof. Dweck is right, our mindset has a big impact on how well we achieve our potential—in school and in many other areas of our lives (for example, in sports, music, and business). But where do these different mindsets come from?

There can be many reasons that a person comes to believe that intelligence is fixed or changeable, but one obvious influence on our way of thinking about ourselves is the messages we hear from adults as we grow up. Dweck and her then-graduate student Claudia Mueller wanted to see if they could influence the mindset of children, if only for a brief period of time, by giving different kinds of praise to the children. Their starting point was the unsurprising and well-established idea that praise is motivating. When we do something and receive praise, we are more likely to want to do that same thing again. But Mueller and Dweck wondered if all praise is equal. In particular, is it possible that certain types of praise that well-meaning parents and teachers often use could actually reduce a child’s motivation to learn and that child’s resiliency when he or she encounters challenges?

The researchers recruited 128 fifth graders (70 girls and 58 boys ranging in age from 10 to 12) to participate in their study. Before we go into the details of the first experiment, please get a feel for the task that the children had to perform.

You will have one minute to solve as many of the problems below as you can.[1] For each problem, you will see a set of patterns arranged in a 3×3 matrix. Each matrix has one item missing, and your task is to figure out what the missing item is based on the changing patterns in the rows, columns, and diagonals.

Try It

Before we start, here is one practice item. The 3×3 matrix is at the top and the pattern on the lower right is missing. Figure out which one of the eight patterns on the bottom, labeled 1 to 8, is the missing pattern.

Show Answer

The correct answer is pattern #7. The pattern on the right in each row combines the dots from the other two patterns in that row.

Try It

Now you will have ONE MINUTE to solve as many of the problems below as possible.

Now that you’ve taken the test, how much would you like to try some more of these questions?

- Not at all

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Very much

How much did you enjoy working on these problems?

- Not at all

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Very much

How well do you think you did on these problems overall?

- Not very well

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Very well

If we gave you some more problems, would you prefer some more like the easier practice problem or some more like the hardest test problem you tried?

- Like the easier practice problem

- Like the hardest test problem

The problem-solving task you just tried is based on a widely used psychological test called the Raven’s Progressive Matrices. Most people find the test to be challenging, requiring close attention to detail and careful logical thinking. Mueller and Dweck chose this task because it could be adapted to be relatively easy or extremely difficult by changing the complexity of the patterns required for solution.

The experiment had three stages, each based around a different set of matrix problems like the ones you worked on. Each child was tested one-on-one in an otherwise empty classroom by a research assistant.

Stage 1: Pretest, Treatment, and Assessment of Motivation

Pretest

The children were given instructions and 10 problems of that were fairly easy to solve. At the end of 4 minutes, they were stopped and the research assistant scored their answers. On average, the children attempted to answer 7.9 out of the 10 problems, and the mean number correct was 5.2.

Treatment

When you do something to manipulate an independent variable, that something you do (administer a pill, tell the participant something that might affect performance, etc.) is called a “treatment.” In this case, the treatment was the feedback the child received about his or her performance on the progressive matrices task. This treatment involved a bit of deception, because children received randomly assigned feedback. In other words, regardless of real performance, the children heard one of three statements depending on random assignment to a treatment condition.

- First, every child was told: “Wow, you did very well on these problems. You got _____ right. That’s a really high score.” The minimum number right that a child heard was 80%, which is obviously well above the actual average of 51%. If a child got more than 80% correct, the actual number correct was used.

- The next step was based on the treatment condition the child had been assigned to:

- Some of the children were praised for their ABILITY: “You must be smart at these problems.”

- Other children were praised for their EFFORT: “You must have worked hard at these problems.”

- The remaining children were in the CONTROL condition. They did not receive any additional feedback, aside from the general praise shown above.

Assessment

After receiving feedback and, for children in two of the conditions, additional praise, the children were asked a series of questions. The experimenters wanted to know if the success the children experienced in the first set of problems, along with the type of praise, influenced their choice of additional problems. They were told that they might get some more problems to solve and they were asked to choose the difficulty of those problems. There were several options, but the choice came down to this:

-

- Give me easy problems: “Problems that I’m pretty good at, so I can show that I’m smart.”

- Give me challenging problems: “Problems that I’ll learn a lot from, even if I won’t look so smart.”

The children were then told that there might be some time at the end of the session to work on these problems they had chosen, but that the next problems they would work on had been determined before the experiment started. They were told this so they would not interpret the next problem set as being “easy” or “challenging” based on their selection.

The results showed that the children were genuinely influenced by the praise they had received. The figure below shows the percentage of children choosing EASY problems, broken down by treatment condition. The children who were praised for how smart they were (ability) were far more likely to choose easy problems than were the children praise for working hard (effort). The control condition, children who were told they did well, but received no additional praise, were in the middle.

Stage 2: Failure, Negative Feedback, and Consequences

Failure

Next, the children tried to solve a new set of 10 matrix problems and again they had 4 minutes. On the surface, these problems looked about the same as the first set, but they were considerably more difficult. After the 4-minute test period, the researchers scored the answers and, regardless of actual performance, they told the children that they had done poorly (“a lot worse”). No one was told that he or she had solved more than 50% correctly. In fact, this feedback was accurate. The results showed that the children found the problems difficult. On average, they attempted 5.8 of the 10 problems and correctly solved only 1.8 of them. There was no significant difference in number of problems solved for the three groups (ability feedback, effort feedback, and no-feedback control).

Consequences

Now the experimenters wanted to know about the effect of “failure” on the children’s motivation (though the term “failure” was never used with the children).

Immediately after receiving feedback, the children were asked a series of questions:

- “How much would you like to take these problems home to work on?” [This was a measure of “task persistence”]

- “How much did you like working on the first set of problems? How much did you enjoy working on the second set? How much fun were the problems? [These measured “task enjoyment”]

- Using a somewhat complicated measure, the children were also asked to explain their difficulties with the second problem set by attributing failure to lack of ability or lack of effort. This was done in a way that they could explain their problems on the second set as partially due to low ability and partially to low effort.

Results

- “How much would you like to take these problems home?” The children answered on a 1-to-6 scale, where higher numbers means more interest in taking the problems home to practice.

- “How much fun were the problems?” The children answered on a 1-to-6 scale, where higher numbers means more enjoyment of the problems.

- Why did you perform poorly on this second set of problems? The children expressed their own explanation for their poor performance using a somewhat complicated procedure. It was not a simple ability vs. effort choice and they could apportion their failure partially to either cause (reference the original study for more details).

Stage 3: Posttest

For the last stage of the experiment, the children were given a new set of problems that was similar in difficulty to the first set. The problems were moderately difficult, and the children had 4 minutes to solve as many as possible. The figure below shows the change in the average number of problems between the pretest (Stage 1) and the posttest (Stage 3).

Try It

Instructions: Click and drag the circles on the right (Posttest) to where you think they should be to reflect the results of the experiment. When you’re done, click the link below to see the actual results.

The Mueller and Dweck experiment shows how a single comment to a child can have at least a temporary effect. It is unlikely that these children were still influenced by that one comment (“You’re smart!” or “You worked hard!”) a day later or even an hour later. But at least for a short time in a controlled setting, the children were apparently affected by what the adult researcher said to them. Why would this matter? If a child repeatedly and consistently hears one sort of encouragement or the other, the child can internalize that way of thinking. Later, as an adolescent and then an adult, the individual’s “mindset” can determine how that person approaches new opportunities to learn and to grow intellectually.

Before you go on, we’d like you to create a psychological theory. This may sound like a strange thing to do, because theories are often presented to you in textbooks as being the final summary of some research. Sometimes that is true, but the primary use of theories in real scientific research is as a temporary and changeable summary of a researcher’s ideas.

Try It

Using the figure below, which shows a sequence of influences beginning with either praise for effort or praise for ability, build a psychological theory.

This is the psychological theory based on Dr. Dweck’s ideas, showing how the two different mindsets lead to different outcome.[2]

What this theory says is that different kinds of praise encourage the child to focus on different goals. Praise for effort tells the child that the process of learning is important and reward comes from trying hard. Praise for ability tells the child that performance comes from something mysterious inside of you (“intelligence” or “talent”) rather than from what you do.

According to the theory (and supported by the results), children who had been praised for effort could focus on the process of learning, so failure at hard problems could be seen as a challenge—even something fun—and failure could motivate them. The children who were praised for their intelligence, which effort cannot change, felt smart when they had easy problems, but the hard problems led to a disturbing realization: maybe I don’t have that magical ability.

At stage 3 in the experiment, children who were energized by the difficult problems tackled the final set of problems, which were fairly easy, with enthusiasm that led to success. The children who were discouraged by failure handicapped themselves on the last set of problems, doing worse than they had at the beginning of the study.

Next, let’s read about a second study by Dweck’s research team, though this one is described more briefly and with less detail. Study 2 is not an experiment because there are no manipulated variables. It is a longitudinal study, which means that the same participants (in this case, children) are tested repeatedly across a long period of time.

Study 2: Blackwell, Trzesniewski, and Dweck (2007)

In this study[3], Dweck and her colleagues administered a questionnaire about beliefs and attitudes to some 7th graders in public schools, and then they tracked 373 of the students from the beginning of the 7th grade to the end of 8th grade. This period, which marked the transition from elementary school to junior high school, was considered a particularly interesting time because it was a challenging, even stressful, time for the students and the children’s learning styles and attitudes could now have a substantial impact on their academic achievement.

At the beginning of their 7th grade school year, the children were tested on their mindset (various levels of commitment to fixed or growth mindset), learning goals (preference for easy or challenging work), beliefs about effort (whether it tends to lead to improvement or not), and attitudes about failure (whether it is motivating or discouraging).

The researchers focused on the students’ mathematics grades across the two years of the study. They chose mathematics because students tend to have strong beliefs about their skills (“I’m good at math” or “I’m not a math person”), which is influenced by their mindset and because math proficiency can be tested and graded fairly objectively. Although the study focused on math, the researchers were interested in any area of study or skill, not just math.

The figure below shows the average grades[4] of the students with strong fixed and strong growth mindsets based on the initial test. Students with mixed mindsets are not included in this graph. At the end of the first semester, there was a very modest difference of less than two points in math grades. The trends for the two lines are obviously different. The students with the fixed mindset (red line) showed a slight decline in average grades across the two years of the study. Students with the growth mindset (green line) show steady improvement across the two years, with their average grade increasing by nearly 3-points.

At the beginning of the study, the students—then just starting the first term of the 7th grade—filled out a questionnaire about their attitudes and beliefs about learning. The table below summarizes these differences.[5] The reason for these questions is an important part of the psychology of learning. Mindset itself (fixed vs. growth) doesn’t cause better or worse performance. Mindset leads to behaviors (types of studying, reactions to setbacks) that in turn affects the quality of learning.

The researchers found that children with growth mindset (related to EFFORT praise in the first study) had different attitudes than children with fixed mindsets (related to ABILITY praise in the first study). The table below summarizes their findings.

| Fixed Mindset | Growth Mindset | |

| Preferred difficulty of work | Easy success | Challenging |

| Belief about value of effort | Doesn’t lead to improvement | Leads to improvement |

| Attitude about failure | Discouraging | Motivating |

The table indicates that children with different mindsets sought out different kinds of experience, with growth mindset children preferring challenging experiences, while those with a fixed mindset preferred easier learning experiences that led to easy success. The growth mindset students believed that working hard—effort—leads to improvement, while those with fixed mindsets tended to undervalue effort, believing that hard work is frustrating because we can’t do better than our “talents” or “innate abilities” allow us to do. Finally, the growth mindset children found difficult work and even failure to be a source of inspiration. They wanted to prove to themselves and others that they could do what was needed to succeed. The fixed mindset children tended to respond to difficulty and failure with discouragement, believing that it simply reaffirmed their own limitations.

Takeaways

The two studies we have discussed are just two of dozens of research projects by Dweck and others that show how mindset is related to differences in achievement. In another study, Grant and Dweck (2003) followed several hundred college students taking a pre-med organic chemistry course, as this is one of the most important and challenging courses for pre-med students at most universities. Students with a growth mindset outperformed students with a fixed mindset, and the two groups reported differences in attitudes and beliefs similar to those shown in the table above.

Mindset is just one factor that influences how we learn and how we respond to challenges. Whether you have a growth mindset or a fixed mindset, you can study hard and do well in school and in other areas. Here is a summary point from Carol Dweck: “It should be noted that in these studies…students who have a fixed mindset but who are well prepared and do not encounter difficulties can do just fine. However, when they encounter challenges or obstacles they may then be at a disadvantage.”

One last thing to remember is this: you can change your mindset. If you regularly handicap yourself by your beliefs (I just don’t have the talent for this) and attitudes about learning (I can’t learn this), you can change those beliefs and attitudes. That change in mindset can be the difference between an effective response to challenges or an avoidance of those challenges. Keep in mind that your beliefs and attitudes are the result of many years of experience, so you won’t change your mindset overnight by simply deciding to be different. You may have to work at it. In particular, when you encounter difficulty—a poor grade on a test, a paper that has some negative comments from your professor, or a reading assignment that leaves you confused—that is the time that your mindset can have a huge impact on what you do next. Don’t let your mindset prevent you from realizing your abilities or reaching your potential!

Module References (Click to expand)

Ahima, R. S., & Antwi, D. A. (2008). Brain regulation of appetite and satiety. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 37, 811–823.

Allen, L. S., & Gorski, R. A. (1992). Sexual orientation and the size of the anterior commissure in the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 89, 7199–7202.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Feeding and eating disorders. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/documents/eating%20disorders%20fact%20sheet.pdf

Arnold, H. J. (1976). Effects of performance feedback and extrinsic reward upon high intrinsic motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 17, 275–288.

Bailey, M. J., & Pillard, R. C. (1991). A genetic study of male sexual orientation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 1089–1096.

Baldwin, J. D., & Baldwin, J. I. (1989). The socialization of homosexuality and heterosexuality in a non-western society. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 18, 13–29.

Bancroft, J. (2004). Alfred C. Kinsey and the politics of sex research. Annual Review of Sex Research, 15, 1–39.

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Bauminger, N. (2002). The facilitation of social-emotional understanding and social interaction in high-functioning children with autism: Intervention outcomes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32, 283–298.

Becker, J. B., Rudick, C. N., & Jenkins, W. J. (2001). The role of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and striatum during sexual behavior in the female rat. Journal of Neuroscience, 21, 3236–3241.

Becker, J. M. (2012, April 25). Dr. Robert Spitzer apologizes to gay community for infamous “ex-gay” study [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.truthwinsout.org/news/2012/04/24542/

Beedie, C. J., Terry, P. C., Lane, A. M., & Devonport, T. J. (2011). Differential assessment of emotions and moods: Development and validation of the emotion and mood components of anxiety questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 228–233.

Bell, A. P., Weinberg, M. S., & Hammersmith, S. K. (1981). Sexual preferences: Its development in men and women. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Berlyne, D. E. (1960). Toward a theory of exploratory behavior: II. Arousal potential, perceptual curiosity, and learning. In (Series Ed.), Conflict, arousal, and curiosity (pp. 193–227). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Bhasin, S., Enzlin, P., Coviello, A., & Basson, R. (2007). Sexual dysfunction in men and women with endocrine disorders. The Lancet, 369, 597–611.

Blackford, J. U., & Pine, D. S. (2012). Neural substrates of childhood anxiety disorders: A review of neuroimaging findings. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 21, 501–525.

Bremner, J. D., & Vermetten, E. (2004). Neuroanatomical changes associated with pharmacotherapy in posttraumatic stress disorder. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1032, 154–157.

Buck, R. (1980). Nonverbal behavior and the theory of emotion: The facial feedback hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 811–824.

Bullough, V. L. (1998). Alfred Kinsey and the Kinsey report: Historical overview and lasting contributions. The Journal of Sex Research, 35, 127–131.

Byne, W., Tobet, S., Mattiace, L. A., Lasco, M. S., Kemether, E., Edgar, M. A., . . . Jones, L. B. (2001). The interstitial nuclei of the human anterior hypothalamus: An investigation of variation with sex, sexual orientation, and HIV status. Hormones and Behavior, 40, 86–92.

Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (1994). Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 64, 363–423.

Carey, B. (2012, May 18). Psychiatry giant sorry for backing gay ‘cure.’ The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/19/health/dr-robert-l-spitzer-noted-psychiatrist-apologizes-for-study-on-gay-cure.html?_r=0

Carter, C. S. (1992). Hormonal influences on human sexual behavior. In J. B. Becker, S. M. Breedlove, & D. Crews (Eds.), Behavioral Endocrinology (pp.131–142). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cassidy, S. B., & Driscoll, D. J. (2009). Prader-Willi syndrome. European Journal of Human Genetics, 17, 3–13.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Overweight and obesity. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/index.html

Chwalisz, K., Diener, E., & Gallagher, D. (1988). Autonomic arousal feedback and emotional experience: Evidence from the spinal cord injured. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 820–828.

Colapinto, J. (2000). As nature made him: The boy who was raised as a girl. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Collier, D. A., & Treasure, J. L. (2004). The aetiology of eating disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 185, 363–365.

Conrad, P. (2005). The shifting engines of medicalization. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 3–14.

Cunha, C., Monfils, M. H., & LeDoux, J. E. (2010). GABA(C) receptors in the lateral amygdala: A possible novel target for the treatment of fear and anxiety disorders? Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 4, 6.

Daniel, T. L., & Esser, J. K. (1980). Intrinsic motivation as influenced by rewards, task interest, and task structure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 566–573.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of emotions in man and animals. New York, NY: Appleton.

Davis, J. I., Senghas, A., & Ochsner, K. N. (2009). How does facial feedback modulate emotional experience? Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 822–829.

Deci, E. L. (1972). Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic reinforcement, and inequity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 22, 113–120.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627–668.

de Gelder, B. (2006). Towards the neurobiology of emotional body language. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7, 242–249.

Drazen, D. L., & Woods, S. C. (2003). Peripheral signals in the control of satiety and hunger. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 5, 621–629.

Druce, M.R., Small, C.J., & Bloom, S.R. (2004). Minireview: Gut peptides regulating satiety. Endocrinology, 145, 2660–2665.

Ekman, P., & Keltner, D. (1997). Universal facial expressions of emotion: An old controversy and new findings. In U. Segerstråle & P. Molnár (Eds.), Nonverbal communication: Where nature meets culture (pp. 27–46). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Everett, B. J. (1990). Sexual motivation: A neural and behavioural analysis of the mechanisms underlying appetitive and copulatory responses of male rats. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 14, 217–232.

Faris, E. (1921). Are instincts data or hypotheses? American Journal of Sociology, 27, 184–196.

Femenía, T., Gómez-Galán, M., Lindskog, M., & Magara, S. (2012). Dysfunctional hippocampal activity affects emotion and cognition in mood disorders. Brain Research, 1476, 58–70.

Fossati, P. (2012). Neural correlates of emotion processing: From emotional to social brain. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 22, S487–S491.

Fournier, J. C., Keener, M. T., Almeida, J., Kronhaus, D. M., & Phillips, M. L. (2013). Amygdala and whole-brain activity to emotional faces distinguishes major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. Advance online publication. doi:10.1111/bdi.12106

Francis, N. H., & Kritsonis, W. A. (2006). A brief analysis of Abraham Maslow’s original writing of Self-Actualizing People: A Study of Psychological Health. Doctoral Forum National Journal of Publishing and Mentoring Doctoral Student Research, 3, 1–7.

Gloy, V. L., Briel, M., Bhatt, D. L., Kashyap, S. R., Schauer, P. R., Mingrone, G., . . . Nordmann, A. J. (2013, October 22). Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ, 347. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f5934

Golan, O., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2006). Systemizing empathy: Teaching adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism to recognize complex emotions using interactive multimedia. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 591–617.

Goosens, K. A., & Maren, S. (2002). Long-term potentiation as a substrate for memory: Evidence from studies of amygdaloid plasticity and Pavlovian fear conditioning. Hippocampus, 12, 592–599.

Graham, S., & Weiner, B. (1996). Theories and principles of motivation. In D. C. Berliner & R. C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 63–84). New York, NY: Routledge.

Greary, N. (1990). Pancreatic glucagon signals postprandial satiety. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 14, 323–328.

Guastella, A. J., Einfeld, S. L., Gray, K. M., Rinehart, N. J., Tonge, B. J., Lambert, T. J., & Hickie, I. B. (2010). Intranasal oxytocin improves emotion recognition for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 67, 692–694.

Hall, J. A., & Kimura, D. (1994). Dermatoglyphic asymmetry and sexual orientation in men. Behavioral Neuroscience, 108(6), 1203–1206.

Hamer, D. H., Hu. S., Magnuson, V. L., Hu, N., & Pattatucci, A. M. (1993). A linkage between DNA markers on the X chromosome and male sexual orientation. Science, 261, 321-327.

Havas, D. A., Glenberg, A. M., Gutowski, K. A., Lucarelli, M. J., & Davidson, R. J. (2010). Cosmetic use of botulinum toxin-A affects processing of emotional language. Psychological Science, 21, 895–900.

Hobson, R. P. (1986). The autistic child’s appraisal of expressions of emotion. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27, 321–342.

Hock, R. R. (2008). Emotion and Motivation. In Forty studies that changed psychology: Explorations into the history of psychological research (6th ed.) (pp. 158–168). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hu, S. H., Wei, N., Wang, Q. D., Yan, L. Q., Wei, E.Q., Zhang, M. M., . . . Xu, Y. (2008). Patterns of brain activation during visually evoked sexual arousal differ between homosexual and heterosexual men. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 29, 1890–1896.

Human Rights Campaign. (n.d.). The lies and dangers of efforts to change sexual orientation or gender identity. Retrieved from http://www.hrc.org/resources/entry/the-lies-and-dangers-of-reparative-therapy

Jenkins, W. J. (2010). Can anyone tell me why I’m gay? What research suggests regarding the origins of sexual orientation. North American Journal of Psychology, 12, 279–296.

Jenkins, W. J., & Becker, J. B. (2001). Role of the striatum and nucleus accumbens in paced copulatory behavior in the female rat. Behavioural Brain Research, 121, 19–28.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company.

Koltko-Rivera, M. E. (2006). Rediscovering the later version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification. Review of General Psychology, 10, 302–317.

Konturek, S. J., Pepera, J., Zabielski, K., Konturek, P. C., Pawlick, T., Szlachcic, A., & Hahn. (2003). Brain-gut axis in pancreatic secretion and appetite control. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 54, 293–317.

Lang, P. J. (1994). The varieties of emotional experience: A meditation on James-Lange theory. Psychological Review, 101, 211–221.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

LeDoux, J. E. (1996). The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

LeDoux, J. E. (2002). The synaptic self. London, UK: Macmillan.

Leonard, G. (1982). The failure of self-actualization theory: A critique of Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 22, 56–73.

LeVay, S. (1991). A difference in the hypothalamic structure between heterosexual and homosexual men. Science, 253, 1034–1037.

LeVay, S. (1996). Queer science: The use and abuse of research into homosexuality. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Levy-Gigi, E., Szabó, C., Kelemen, O., & Kéri, S. (2013). Association among clinical response, hippocampal volume, and FKBP5 gene expression in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder receiving cognitive behavioral therapy. Biological Psychiatry, 74, 793–800.

Lippa, R. A. (2003). Handedness, sexual orientation, and gender-related personality traits in men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 103–114.

Loehlin, J. C., & McFadden, D. (2003). Otoacoustic emissions, auditory evoked potentials, and traits related to sex and sexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 115–127.

Macdonald, H., Rutter, M., Howlin, P., Rios, P., Conteur, A. L., Evered, C., & Folstein, S. (1989). Recognition and expression of emotional cues by autistic and normal adults. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30, 865–877.

Malatesta, C. Z., & Haviland, J. M. (1982). Learning display rules: The socialization of emotion expression in infancy. Child Development, 53, 991–1003.

Maren, S., Phan, K. L., & Liberzon, I. (2013). The contextual brain: Implications for fear conditioning, extinction and psychopathology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14, 417–428.

Martin-Gronert, M. S., & Ozanne, S. E. (2013). Early life programming of obesity. Developmental Period Medicine, 17, 7–12.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396.

Matsumoto, D. (1990). Cultural similarities and differences in display rules. Motivation and Emotion, 14, 195–214.

Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., & Nakagawa, S. (2008). Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 925–937.

Mayo Clinic. (2012a). Anorexia nervosa. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/anorexia/DS00606

Mayo Clinic. (2012b). Bulimia nervosa. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/bulimia/DS00607

Mayo Clinic. (2013). Gastric bypass surgery. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/gastric-bypass/MY00825

McAdams, D. P., & Constantian, C. A. (1983). Intimacy and affiliation motives in daily living: An experience sampling analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 851–861.

McClelland, D. C., & Liberman, A. M. (1949). The effect of need for achievement on recognition of need-related words. Journal of Personality, 18, 236–251.

McFadden, D., & Champlin, C. A. (2000). Comparisons of auditory evoked potentials in heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual males and females. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 1, 89–99.

McFadden, D., & Pasanen, E. G. (1998). Comparisons of the auditory systems of heterosexuals and homosexuals: Clicked-evoked otoacoustic emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 95, 2709–2713.

McRae, K., Ochsner, K. N., Mauss, I. B., Gabrieli, J. J. D., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Gender differences in emotion regulation: An fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 11, 143–162.

Miguel-Hidalgo, J. J. (2013). Brain structural and functional changes in adolescents with psychiatric disorders. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 25, 245–256.

Money, J. (1962). Cytogenic and psychosexual incongruities with a note on space-form blindness. Paper presented at the 118th meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Toronto, Canada.

Money, J. (1975). Ablatio penis: Normal male infant sex-reassigned as a girl. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 4, 65–71.

Moriceau, S., & Sullivan, R. M. (2006). Maternal presence serves as a switch between learning fear and attraction in infancy. Nature Neuroscience, 9, 1004–1006.

Murray, H. A., Barrett, W. G., Homburger, E., Langer, W. C., Mekeel, H. S., Morgan, C. D., . . . Wolf, R. E. (1938). Explorations in personality: A clinical and experimental study of fifty men of college age. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7, 133–144.

Novin, D., Robinson, K., Culbreth, L. A., & Tordoff, M. G. (1985). Is there a role for the liver in the control of food intake? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 42, 1050–1062.

O’Connell, S. (Writer/Producer). (2004). Dr. Money and the boy with no penis. [Television documentary series episode]. In Horizon. London, UK: BBC.

Paramaguru, K. (2013, November). Boy, girl, or intersex? Germany adjusts to a third option at birth. Time. Retrieved from http://world.time.com/2013/11/12/boy-girl-or-intersex/

Pessoa, L. (2010). Emotion and cognition and the amygdala: From “what is it?” to “what’s to be done?” Neuropsychologia, 48, 3416–3429.

Pillard, R. C., & Bailey, M. J. (1995). A biologic perspective on sexual orientation. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 18(1), 71–84.

Pillard, R. C., & Bailey, M. J. (1998). Sexual orientation has a heritable component. Human Biology, 70, 347–365.

Ponseti, J., Bosinski, H. A., Wolff, S., Peller, M., Jansen, O., Mehdorn, H.M., . . . Siebner, H. R. (2006). A functional endophenotype for sexual orientation in humans. Neuroimage, 33(3), 825–833.

Prader-Willi Syndrome Association. (2012). What is Prader-Willi Syndrome? Retrieved from http://www.pwsausa.org/syndrome/index.htm

Qin, S., Young, C. B., Duan, X., Chen, T., Supekar, K., & Menon, V. (2013). Amygdala subregional structure and intrinsic functional connectivity predicts individual differences in anxiety during early childhood. Biological Psychiatry. Advance online publication. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.10.006

Rahman, Q., & Wilson, G. D. (2003a). Large sexual-orientation-related differences in performance on mental rotation and judgment of line orientation tasks. Neuropsychology, 17, 25–31.

Rahman, Q., & Wilson, G. D. (2003b). Sexual orientation and the 2nd to 4th finger length ratio: Evidence for organising effects of sex hormones or developmental instability? Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28, 288–303.

Raineki, C., Cortés, M. R., Belnoue, L., & Sullivan, R. M. (2012). Effects of early-life abuse differ across development: Infant social behavior deficits are followed by adolescent depressive-like behaviors mediated by the amygdala. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 7758–7765.

Rodriguez-Larralde, A., & Paradisi, I. (2009). Influence of genetic factors on human sexual orientation. Investigacion Clinica, 50, 377–391.

Ross, M. W., & Arrindell, W. A. (1988). Perceived parental rearing patterns of homosexual and heterosexual men. The Journal of Sex Research, 24, 275–281.

Saxe, L., & Ben-Shakhar, G. (1999). Admissibility of polygraph tests: The application of scientific standards post-Daubert. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 5, 203–223.

Schachter, S., & Singer, J. E. (1962). Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological Review, 69, 379–399.

Sherwin, B. B. (1988). A comparative analysis of the role of androgen in human male and female sexual behavior: Behavioral specificity, critical thresholds, and sensitivity. Psychobiology, 16, 416–425.

Smink, F. R. E., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012). Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14, 406–414.

Soussignan, R. (2001). Duchenne smile, emotional experience, and autonomic reactivity: A test of the facial feedback hypothesis. Emotion, 2, 52–74.

Speakman, J. R., Levitsky, D. A., Allison, D. B., Bray, M. S., de Castro, J. M., Clegg, D. J., . . . Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S. (2011). Set points, settling points and some alternative models: Theoretical options to understand how genes and environment combine to regulate body adiposity. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 4, 733–745.

Strack, F., Martin, L. & Stepper, S. (1988). Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: A nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 768–777.

Swaab, D. F., & Hofman, M. A. (1990). An enlarged suprachiasmatic nucleus in homosexual men. Brain Research, 537, 141–148.

Tamietto, M., Castelli, L., Vighetti, S., Perozzo, P., Geminiani, G., Weiskrantz, L., & de Gelder, B. (2009). Unseen facial and bodily expressions trigger fast emotional reactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,USA, 106, 17661–17666.

Tangmunkongvorakul, A., Banwell, C., Carmichael, G., Utomo, I. D., & Sleigh, A. (2010). Sexual identities and lifestyles among non-heterosexual urban Chiang Mai youth: Implications for health. Culture, Health, and Sexuality, 12, 827–841.

Wang, Z., Neylan, T. C., Mueller, S. G., Lenoci, M., Truran, D., Marmar, C. R., . . . Schuff, N. (2010). Magnetic resonance imaging of hippocampal subfields in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 67(3), 296–303. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.205

Weinsier, R. L., Nagy, T. R., Hunter, G. R., Darnell, B. E., Hensrud, D. D., & Weiss, H. L. (2000). Do adaptive changes in metabolic rate favor weight regain in weight-reduced individuals? An examination of the set-point theory. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72, 1088–1094.

Woods, S. C. (2004). Gastrointestinal satiety signals I. An overview of gastrointestinal signals that influence food intake. American Journal of Physiology: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 286, G7–G13.

Woods, S. C., & D’Alessio, D. A. (2008). Central control of body weight and appetite. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 93, S37–S50.

Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459–482. doi:10.1002/cne.920180503

Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35(2), 151–175.

Zajonc, R. B. (1998). Emotions. In D. T. Gilbert & S. T. Fiske (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 591–632). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Licenses and Attributions (Click to expand)

CC licensed content, Original

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Modification and adaptation, addition of link to learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Introduction to Emotion and Motivation. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/10-introduction. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Motivation. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/10-1-motivation. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- climbing picture. Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: https://www.pexels.com/photo/achievement-action-adventure-backlit-209209/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Motivation. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/10-1-motivation. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

All rights reserved content

- RSA ANIMATE: Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Authored by: Dan Pink. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6XAPnuFjJc. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Questions used with permission from http://www.smart-kit.com/scategory/brain-teasers/iq-test-questions/ ↵

- This particular version of her theory did not come directly from her papers. We have put them together in this form to illustrate how experience can influence thinking which then influences behavior. ↵

- Lisa S. Blackwell, Kali H. Trzesniewski, and Carol S. Dweck (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across and adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, January/February 2007, Volume 78, Number 1, Pages 246 – 263. ↵

- More accurately, predicted grades from growth curves based on data and using a technique called hierarchical linear modeling. ↵

- This table is not in the research paper. It is based on correlations between answers to the mindset question and answers to questions about these other issues. See Table 1 of the published study. ↵

wants or needs that direct behavior toward some goal

motivation based on internal feelings rather than external rewards

motivation that arises from external factors or rewards

species-specific pattern of behavior that is unlearned

deviations from homeostasis create physiological needs that result in psychological drive states that direct behavior to meet the need and ultimately bring the system back to homeostasis

pattern of behavior in which we regularly engage

simple tasks are performed best when arousal levels are relatively high, while complex tasks are best performed when arousal is lower

individual’s belief in his own capabilities or capacities to complete a task

spectrum of needs ranging from basic biological needs to social needs to self-actualization

Raven's Progressive Matrices (RPM) is a non-verbal assessment used to measure general intelligence and abstract reasoning abilities. It presents a series of increasingly complex patterns with a missing piece, requiring the test-taker to identify the correct element to complete the pattern. The test is widely used across different age groups and cultural backgrounds, making it a versatile tool for assessing cognitive abilities.