Chapter 8: Thinking and Intelligence

8.2 Language

Learning Objectives

- Define basic terms used to describe language use

- Characterize the typical content of conversation and its social implications

- Understand how the use of language develops

- Explain the relationship between language and thinking

Introduction to Language

What you’ll learn to do: describe language acquisition and the role language plays in communication and thought

Language is a communication system that involves using words and systematic rules to organize those words to transmit information from one individual to another. While language is a form of communication, not all communication is language. Many species communicate with one another through their postures, movements, odors, or vocalizations. This communication is crucial for species that need to interact and develop social relationships with their conspecifics. However, many people have asserted that it is language that makes humans unique among all of the animal species (Corballis & Suddendorf, 2007; Tomasello & Rakoczy, 2003). This section will focus on what distinguishes language as a special form of communication, how the use of language develops, and how language affects the way we think.

Language and Language Use

Adam: “You know, Gary bought a ring.” Ben: “Oh yeah? For Mary, isn’t it?” (Adam nods.)

If you are watching this scene and hearing their conversation, what can you guess from this? First of all, you’d guess that Gary bought a ring for Mary, whoever Gary and Mary might be. Perhaps you would infer that Gary is getting married to Mary. What else can you guess? Perhaps that Adam and Ben are fairly close colleagues, and both of them know Gary and Mary reasonably well. In other words, you can guess the social relationships surrounding the people who are engaging in the conversation and the people whom they are talking about.

Language is used in our everyday lives. If psychology is a science of behavior, scientific investigation of language use must be one of the most central topics—this is because language use is ubiquitous. Every human group has a language; human infants (except those who have unfortunate disabilities) learn at least one language without being taught explicitly. Even when children who don’t have much language to begin with are brought together, they can begin to develop and use their own language. There is at least one known instance where children who had had little language were brought together and developed their own language spontaneously with minimum input from adults. In Nicaragua in the 1980s, deaf children who were separately raised in various locations were brought together to schools for the first time. Teachers tried to teach them Spanish with little success. However, they began to notice that the children were using their hands and gestures, apparently to communicate with each other. Linguists were brought in to find out what was happening—it turned out the children had developed their own sign language by themselves. That was the birth of a new language, Nicaraguan Sign Language (Kegl, Senghas, & Coppola, 1999). Language is ubiquitous, and we humans are born to use it.

How Do We Use Language?

If language is so ubiquitous, how do we actually use it? To be sure, some of us use it to write diaries and poetry, but the primary form of language use is interpersonal. That’s how we learn language, and that’s how we use it. Just like Adam and Ben, we exchange words and utterances to communicate with each other. Let’s consider the simplest case of two people, Adam and Ben, talking with each other. According to Clark (1996), in order for them to carry out a conversation, they must keep track of common ground. Common ground is a set of knowledge that the speaker and listener share and they think, assume, or otherwise take for granted that they share. So, when Adam says, “Gary bought a ring,” he takes for granted that Ben knows the meaning of the words he is using, whom Gary is, and what buying a ring means. When Ben says, “For Mary, isn’t it?” he takes for granted that Adam knows the meaning of these words, who Mary is, and what buying a ring for someone means. All these are part of their common ground.

Note that, when Adam presents the information about Gary’s purchase of a ring, Ben responds by presenting his inference about who the recipient of the ring might be, namely, Mary. In conversational terms, Ben’s utterance acts as evidence for his comprehension of Adam’s utterance—“Yes, I understood that Gary bought a ring”—and Adam’s nod acts as evidence that he now has understood what Ben has said too—“Yes, I understood that you understood that Gary has bought a ring for Mary.” This new information is now added to the initial common ground. Thus, the pair of utterances by Adam and Ben (called an adjacency pair) together with Adam’s affirmative nod jointly completes one proposition, “Gary bought a ring for Mary,” and adds this information to their common ground. This way, common ground changes as we talk, gathering new information that we agree on and have evidence that we share. It evolves as people take turns to assume the roles of speaker and listener, and actively engage in the exchange of meaning.

Common ground helps people coordinate their language use. For instance, when a speaker says something to a listener, he or she takes into account their common ground, that is, what the speaker thinks the listener knows. Adam said what he did because he knew Ben would know who Gary was. He’d have said, “A friend of mine is getting married,” to another colleague who wouldn’t know Gary. This is called audience design (Fussell & Krauss, 1992); speakers design their utterances for their audiences by taking into account the audiences’ knowledge. If their audiences are seen to be knowledgeable about an object (such as Ben about Gary), they tend to use a brief label of the object (i.e., Gary); for a less knowledgeable audience, they use more descriptive words (e.g., “a friend of mine”) to help the audience understand their utterances (Box 1).

So, language use is a cooperative activity, but how do we coordinate our language use in a conversational setting? To be sure, we have a conversation in small groups. The number of people engaging in a conversation at a time is rarely more than four. By some counts (e.g., Dunbar, Duncan, & Nettle, 1995;James, 1953), more than 90 percent of conversations happen in a group of four individuals or less. Certainly, coordinating conversation among four is not as difficult as coordinating conversation among 10. But, even among only four people, if you think about it, everyday conversation is an almost miraculous achievement.

We typically have a conversation by rapidly exchanging words and utterances in real time in a noisy environment. Think about your conversation at home in the morning, at a bus stop, in a shopping mall. How can we keep track of our common ground under such circumstances?

Pickering and Garrod (2004) argue that we achieve our conversational coordination by virtue of our ability to interactively align each other’s actions at different levels of language use: lexicon (i.e., words and expressions), syntax (i.e., grammatical rules for arranging words and expressions together), as well as speech rate and accent. For instance, when one person uses a certain expression to refer to an object in a conversation, others tend to use the same expression (e.g.,Clark & Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986). Furthermore, if someone says “the cowboy offered a banana to the robber,” rather than “the cowboy offered the robber a banana,” others are more likely to use the same syntactic structure (e.g., “the girl gave a book to the boy” rather than “the girl gave the boy a book”) even if different words are involved (Branigan, Pickering, & Cleland, 2000).

Finally, people in conversation tend to exhibit similar accents and rates of speech, and they are often associated with people’s social identity (Giles, Coupland, & Coupland, 1991). So, if you have lived in different places where people have somewhat different accents (e.g., United States and United Kingdom), you might have noticed that you speak with Americans with an American accent, but speak with Britons with a British accent.

Pickering and Garrod (2004) suggest that these interpersonal alignments at different levels of language use can activate similar situation models in the minds of those who are engaged in a conversation. Situation models are representations about the topic of a conversation. So, if you are talking about Gary and Mary with your friends, you might have a situation model of Gary giving Mary a ring in your mind. Pickering and Garrod’s theory is that as you describe this situation using language, others in the conversation begin to use similar words and grammar, and many other aspects of language use converge. As you all do so, similar situation models begin to be built in everyone’s mind through the mechanism known as priming. Priming occurs when your thinking about one concept (e.g., “ring”) reminds you about other related concepts (e.g., “marriage”, “wedding ceremony”). So, if everyone in the conversation knows about Gary, Mary, and the usual course of events associated with a ring—engagement, wedding, marriage, etc.— everyone is likely to construct a shared situation model about Gary and Mary. Thus, making use of our highly developed interpersonal ability to imitate (i.e., executing the same action as another person) and cognitive ability to infer (i.e., one idea leading to other ideas), we humans coordinate our common ground, share situation models, and communicate with each other.

What Do We Talk About?

What are humans doing when we are talking? Surely, we can communicate about mundane things such as what to have for dinner, but also more complex and abstract things such as the meaning of life and death, liberty, equality, and fraternity, and many other philosophical thoughts. Well, when naturally occurring conversations were actually observed (Dunbar, Marriott, & Duncan, 1997), a staggering 60%–70% of everyday conversation, for both men and women, turned out to be gossip—people talk about themselves and others whom they know. Just like Adam and Ben, more often than not, people use language to communicate about their social world.

Gossip may sound trivial and seem to belittle our noble ability for language—surely one of the most remarkable human abilities of all that distinguish us from other animals. Au contraire, some have argued that gossip—activities to think and communicate about our social world—is one of the most critical uses to which language has been put. Dunbar (1996) conjectured that gossiping is the human equivalent of grooming, monkeys and primates attending and tending to each other by cleaning each other’s fur. He argues that it is an act of socializing, signaling the importance of one’s partner. Furthermore, by gossiping, humans can communicate and share their representations about their social world—who their friends and enemies are, what the right thing to do is under what circumstances, and so on. In so doing, they can regulate their social world—making more friends and enlarging one’s own group (often called the ingroup, the group to which one belongs) against other groups (outgroups) that are more likely to be one’s enemies.

Dunbar has argued that it is these social effects that have given humans an evolutionary advantage and larger brains, which, in turn, help humans to think more complex and abstract thoughts and, more important, maintain larger ingroups. Dunbar (1993) estimated an equation that predicts average group size of nonhuman primate genera from their average neocortex size (the part of the brain that supports higher order cognition). In line with his social brain hypothesis, Dunbar showed that those primate genera that have larger brains tend to live in larger groups. Furthermore, using the same equation, he was able to estimate the group size that human brains can support, which turned out to be about 150—approximately the size of modern hunter-gatherer communities. Dunbar’s argument is that language, brain, and human group living have co-evolved—language and human sociality are inseparable. Dunbar’s hypothesis is controversial. Nonetheless, whether or not he is right, our everyday language use often ends up maintaining the existing structure of intergroup relationships.

Language use can have implications for how we construe our social world. For one thing, there are subtle cues that people use to convey the extent to which someone’s action is just a special case in a particular context or a pattern that occurs across many contexts and more like a character trait of the person. According to Semin and Fiedler (1988), someone’s action can be described by an action verb that describes a concrete action (e.g., he runs), a state verb that describes the actor’s psychological state (e.g., he likes running), an adjective that describes the actor’s personality (e.g., he is athletic), or a noun that describes the actor’s role (e.g., he is an athlete). Depending on whether a verb or an adjective (or noun) is used, speakers can convey the permanency and stability of an actor’s tendency to act in a certain way—verbs convey particularity, whereas adjectives convey permanency.

Intriguingly, people tend to describe positive actions of their ingroup members using adjectives (e.g., he is generous) rather than verbs (e.g., he gave a blind man some change), and negative actions of outgroup members using adjectives (e.g., he is cruel) rather than verbs (e.g., he kicked a dog). Maass, Salvi, Arcuri, and Semin (1989) called this a linguistic intergroup bias, which can produce and reproduce the representation of intergroup relationships by painting a picture favoring the ingroup. That is, ingroup members are typically good, and if they do anything bad, that’s more an exception in special circumstances; in contrast, outgroup members are typically bad, and if they do anything good, that’s more an exception.

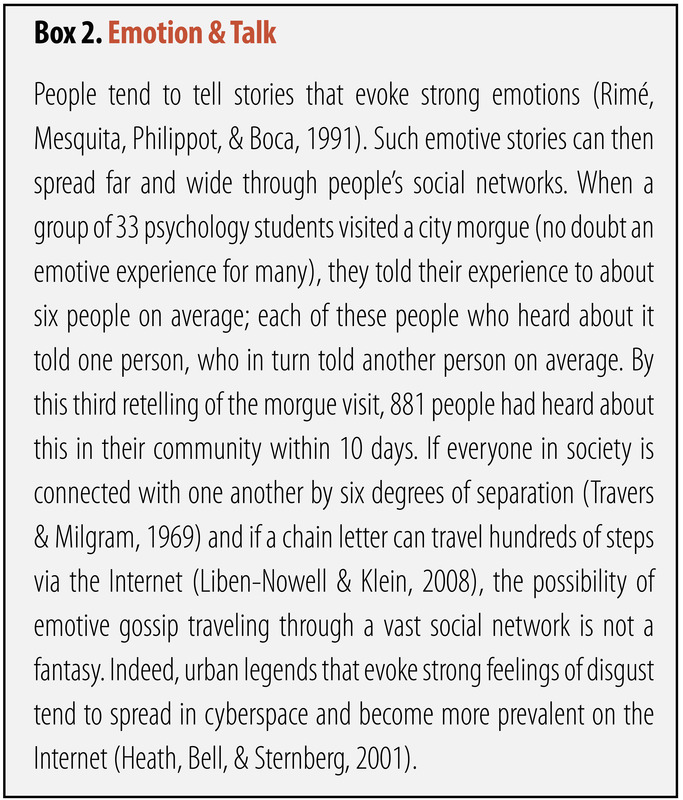

In addition, when people exchange their gossip, it can spread through broader social networks. If gossip is transmitted from one person to another, the second person can transmit it to a third person, who then in turn transmits it to a fourth, and so on through a chain of communication. This often happens for emotive stories (Box 2). If gossip is repeatedly transmitted and spread, it can reach a large number of people. When stories travel through communication chains, they tend to become conventionalized (Bartlett, 1932). A Native American tale of the “War of the Ghosts” recounts a warrior’s encounter with ghosts traveling in canoes and his involvement with their ghostly battle. He is shot by an arrow but doesn’t die, returning home to tell the tale. After his narration, however, he becomes still, a black thing comes out of his mouth, and he eventually dies. When it was told to a student in England in the 1920s and retold from memory to another person, who, in turn, retold it to another and so on in a communication chain, the mythic tale became a story of a young warrior going to a battlefield, in which canoes became boats, and the black thing that came out of his mouth became simply his spirit (Bartlett, 1932). In other words, information transmitted multiple times was transformed to something that was easily understood by many, that is, information was assimilated into the common ground shared by most people in the linguistic community.

More recently, Kashima (2000) conducted a similar experiment using a story that contained sequence of events that described a young couple’s interaction that included both stereotypical and counter-stereotypical actions (e.g., a man watching sports on TV on Sunday vs. a man vacuuming the house). After the retelling of this story, much of the counter-stereotypical information was dropped, and stereotypical information was more likely to be retained. Because stereotypes are part of the common ground shared by the community, this finding too suggests that conversational retellings are likely to reproduce conventional content.

Language Development

Language is a communication system that involves using words and systematic rules to organize those words to transmit information from one individual to another. While language is a form of communication, not all communication is language. Many species communicate with one another through their postures, movements, odors, or vocalizations. This communication is crucial for species that need to interact and develop social relationships with their conspecifics. However, many people have asserted that it is language that makes humans unique among all of the animal species (Corballis & Suddendorf, 2007; Tomasello & Rakoczy, 2003). This section will focus on what distinguishes language as a special form of communication, how the use of language develops, and how language affects the way we think.

Components of Language

Language, be it spoken, signed, or written, has specific components: a lexicon and grammar. Lexicon refers to the words of a given language. Thus, lexicon is a language’s vocabulary. Grammar refers to the set of rules that are used to convey meaning through the use of the lexicon (Fernández & Cairns, 2011). For instance, English grammar dictates that most verbs receive an “-ed” at the end to indicate past tense.

Words are formed by combining the various phonemes that make up the language. A phoneme (e.g., the sounds “ah” vs. “eh”) is a basic sound unit of a given language, and different languages have different sets of phonemes. Phonemes are combined to form morphemes, which are the smallest units of language that convey some type of meaning (e.g., “I” is both a phoneme and a morpheme). Further, a morpheme is not the same as a word. The main difference is that a morpheme sometimes does not stand alone, but a word, by definition, always stands alone.

We use semantics and syntax to construct language. Semantics and syntax are part of a language’s grammar. Semantics refers to the process by which we derive meaning from morphemes and words. Syntax refers to the way words are organized into sentences (Chomsky, 1965; Fernández & Cairns, 2011).

We apply the rules of grammar to organize the lexicon in novel and creative ways, which allow us to communicate information about both concrete and abstract concepts. We can talk about our immediate and observable surroundings as well as the surface of unseen planets. We can share our innermost thoughts, our plans for the future, and debate the value of a college education. We can provide detailed instructions for cooking a meal, fixing a car, or building a fire. The flexibility that language provides to relay vastly different types of information is a property that makes language so distinct as a mode of communication among humans.

Language Development

Given the remarkable complexity of a language, one might expect that mastering a language would be an especially arduous task; indeed, for those of us trying to learn a second language as adults, this might seem to be true. However, young children master language very quickly with relative ease. B. F. Skinner (1957) proposed that language is learned through reinforcement. Noam Chomsky (1965) criticized this behaviorist approach, asserting instead that the mechanisms underlying language acquisition are biologically determined. The use of language develops in the absence of formal instruction and appears to follow a very similar pattern in children from vastly different cultures and backgrounds. It would seem, therefore, that we are born with a biological predisposition to acquire a language (Chomsky, 1965; Fernández & Cairns, 2011). Moreover, it appears that there is a critical period for language acquisition, such that this proficiency at acquiring language is maximal early in life; generally, as people age, the ease with which they acquire and master new languages diminishes (Johnson & Newport, 1989; Lenneberg, 1967; Singleton, 1995).

Children begin to learn about language from a very early age (Table 1). In fact, it appears that this is occurring even before we are born. Newborns show preference for their mother’s voice and appear to be able to discriminate between the language spoken by their mother and other languages. Babies are also attuned to the languages being used around them and show preferences for videos of faces that are moving in synchrony with the audio of spoken language versus videos that do not synchronize with the audio (Blossom & Morgan, 2006; Pickens, 1994; Spelke & Cortelyou, 1981).

| Stage | Age | Developmental Language and Communication |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–3 months | Reflexive communication |

| 2 | 3–8 months | Reflexive communication; interest in others |

| 3 | 8–13 months | Intentional communication; sociability |

| 4 | 12–18 months | First words |

| 5 | 18–24 months | Simple sentences of two words |

| 6 | 2–3 years | Sentences of three or more words |

| 7 | 3–5 years | Complex sentences; has conversations |

Dig Deeper: The Case of Genie

In the fall of 1970, a social worker in the Los Angeles area found a 13-year-old girl who was being raised in extremely neglectful and abusive conditions. The girl, who came to be known as Genie, had lived most of her life tied to a potty chair or confined to a crib in a small room that was kept closed with the curtains drawn. For a little over a decade, Genie had virtually no social interaction and no access to the outside world. As a result of these conditions, Genie was unable to stand up, chew solid food, or speak (Fromkin, Krashen, Curtiss, Rigler, & Rigler, 1974; Rymer, 1993). The police took Genie into protective custody.

Genie’s abilities improved dramatically following her removal from her abusive environment, and early on, it appeared she was acquiring language—much later than would be predicted by critical period hypotheses that had been posited at the time (Fromkin et al., 1974). Genie managed to amass an impressive vocabulary in a relatively short amount of time. However, she never developed a mastery of the grammatical aspects of language (Curtiss, 1981). Perhaps being deprived of the opportunity to learn language during a critical period impeded Genie’s ability to fully acquire and use language.

You may recall that each language has its own set of phonemes that are used to generate morphemes, words, and so on. Babies can discriminate among the sounds that make up a language (for example, they can tell the difference between the “s” in vision and the “ss” in fission); early on, they can differentiate between the sounds of all human languages, even those that do not occur in the languages that are used in their environments. However, by the time that they are about 1 year old, they can only discriminate among those phonemes that are used in the language or languages in their environments (Jensen, 2011; Werker & Lalonde, 1988; Werker & Tees, 1984).

Link to Learning

Watch this video about infant speech discrimination to learn more about how babies lose the ability to discriminate among all possible human phonemes as they age.

After the first few months of life, babies enter what is known as the babbling stage, during which time they tend to produce single syllables that are repeated over and over. As time passes, more variations appear in the syllables that they produce. During this time, it is unlikely that the babies are trying to communicate; they are just as likely to babble when they are alone as when they are with their caregivers (Fernández & Cairns, 2011). Interestingly, babies who are raised in environments in which sign language is used will also begin to show babbling in the gestures of their hands during this stage (Petitto, Holowka, Sergio, Levy, & Ostry, 2004).

Generally, a child’s first word is uttered sometime between the ages of 1 year to 18 months, and for the next few months, the child will remain in the “one word” stage of language development. During this time, children know a number of words, but they only produce one-word utterances. The child’s early vocabulary is limited to familiar objects or events, often nouns. Although children in this stage only make one-word utterances, these words often carry larger meaning (Fernández & Cairns, 2011). So, for example, a child saying “cookie” could be identifying a cookie or asking for a cookie.

As a child’s lexicon grows, she begins to utter simple sentences and to acquire new vocabulary at a very rapid pace. In addition, children begin to demonstrate a clear understanding of the specific rules that apply to their language(s). Even the mistakes that children sometimes make provide evidence of just how much they understand about those rules. This is sometimes seen in the form of overgeneralization. In this context, overgeneralization refers to an extension of a language rule to an exception to the rule. For example, in English, it is usually the case that an “s” is added to the end of a word to indicate plurality. For example, we speak of one dog versus two dogs. Young children will overgeneralize this rule to cases that are exceptions to the “add an s to the end of the word” rule and say things like “those two gooses” or “three mouses.” Clearly, the rules of the language are understood, even if the exceptions to the rules are still being learned (Moskowitz, 1978).

Language and Thinking

What Do You Think?: The Meaning of Language

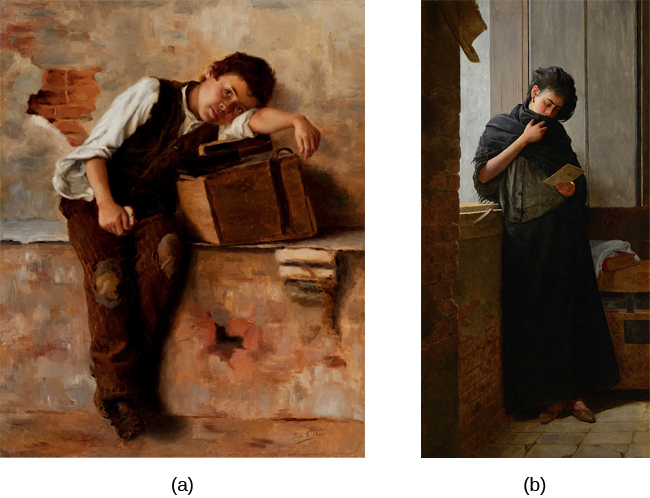

Think about what you know of other languages; perhaps you even speak multiple languages. Imagine for a moment that your closest friend fluently speaks more than one language. Do you think that friend thinks differently, depending on which language is being spoken? You may know a few words that are not translatable from their original language into English. For example, the Portuguese word saudade originated during the 15th century, when Portuguese sailors left home to explore the seas and travel to Africa or Asia. Those left behind described the emptiness and fondness they felt as saudade (Figure 1). The word came to express many meanings, including loss, nostalgia, yearning, warm memories, and hope. There is no single word in English that includes all of those emotions in a single description. Do words such as saudade indicate that different languages produce different patterns of thought in people? What do you think??

Language may indeed influence the way that we think, an idea known as linguistic determinism. One recent demonstration of this phenomenon involved differences in the way that English and Mandarin Chinese speakers talk and think about time. English speakers tend to talk about time using terms that describe changes along a horizontal dimension, for example, saying something like “I’m running behind schedule” or “Don’t get ahead of yourself.” While Mandarin Chinese speakers also describe time in horizontal terms, it is not uncommon to also use terms associated with a vertical arrangement. For example, the past might be described as being “up” and the future as being “down.” It turns out that these differences in language translate into differences in performance on cognitive tests designed to measure how quickly an individual can recognize temporal relationships. Specifically, when given a series of tasks with vertical priming, Mandarin Chinese speakers were faster at recognizing temporal relationships between months. Indeed, Boroditsky (2001) sees these results as suggesting that “habits in language encourage habits in thought” (p. 12).

Language does not completely determine our thoughts—our thoughts are far too flexible for that—but habitual uses of language can influence our habit of thought and action. For instance, some linguistic practice seems to be associated even with cultural values and social institution. Pronoun drop is the case in point. Pronouns such as “I” and “you” are used to represent the speaker and listener of a speech in English. In an English sentence, these pronouns cannot be dropped if they are used as the subject of a sentence. So, for instance, “I went to the movie last night” is fine, but “Went to the movie last night” is not in standard English. However, in other languages such as Japanese, pronouns can be, and in fact often are, dropped from sentences. It turned out that people living in those countries where pronoun drop languages are spoken tend to have more collectivistic values (e.g., employees having greater loyalty toward their employers) than those who use non–pronoun drop languages such as English (Kashima & Kashima, 1998). It was argued that the explicit reference to “you” and “I” may remind speakers the distinction between the self and other, and the differentiation between individuals. Such a linguistic practice may act as a constant reminder of the cultural value, which, in turn, may encourage people to perform the linguistic practice.

One group of researchers who wanted to investigate how language influences thought compared how English speakers and the Dani people of Papua New Guinea think and speak about color. The Dani have two words for color: one word for light and one word for dark. In contrast, the English language has 11 color words. Researchers hypothesized that the number of color terms could limit the ways that the Dani people conceptualized color. However, the Dani were able to distinguish colors with the same ability as English speakers, despite having fewer words at their disposal (Berlin & Kay, 1969). A recent review of research aimed at determining how language might affect something like color perception suggests that language can influence perceptual phenomena, especially in the left hemisphere of the brain. You may recall from earlier chapters that the left hemisphere is associated with language for most people. However, the right (less linguistic hemisphere) of the brain is less affected by linguistic influences on perception (Regier & Kay, 2009)

Link to Learning

Learn more about language, language acquisition, and especially the connection between language and thought in the following CrashCourse video:

You can view the transcript for “Language: Crash Course Psychology #16” here (opens in new window).

Licenses and Attributions (Click to expand)

CC licensed content, Original

- Modification and adaptation. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Language. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/7-2-language. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authored by: geralt. Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: https://pixabay.com/en/school-board-languages-blackboard-1063556/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Language and Language Use. Authored by: Yoshihisa Kashima. Located at: http://nobaproject.com/textbooks/introduction-to-psychology-the-full-noba-collection/modules/language-and-language-use. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Morpheme. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morpheme. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Paragraph on pronoun drop. Authored by: Yoshihisa Kashima . Provided by: University of Melbourne. Located at: http://nobaproject.com/textbooks/wendy-king-introduction-to-psychology-the-full-noba-collection/modules/language-and-language-use. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

All rights reserved content

- Language: Crash Course Psychology #16. Authored by: CrashCourse. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9shPouRWCs&feature=youtu.be&list=PL8dPuuaLjXtOPRKzVLY0jJY-uHOH9KVU6. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

information that is shared by people who engage in a conversation

constructing utterances to suit the audience’s knowledge

words and expressions

rules by which words are strung together to form sentences

a mental representation of an event, object, or situation constructed at the time of comprehending a linguistic description

the process by which recent experiences increase a trait’s accessibility.

group to which a person belongs

group to which a person does not belong

the hypothesis that the human brain has evolved, so that humans can maintain larger ingroups

a tendency for people to characterize positive things about their ingroup using more abstract expressions, but negative things about their outgroups using more abstract expressions.

networks of social relationships among individuals through which information can travel

communication system that involves using words to transmit information from one individual to another

set of rules that are used to convey meaning through the use of a lexicon

basic sound unit of a given language

smallest unit of language that conveys some type of meaning

process by which we derive meaning from morphemes and words

extension of a rule that exists in a given language to an exception to the rule