Chapter 2: Ethical Theory – Kantian Duty Ethics

Ethical Theories: What Are They Good For?

Our study of ethical theory is not intended as an end in itself. Rather, it should be conducted in the service of practice. In other words, the motivation for studying ethical theory is that it will, or at least can, help us think about everyday moral matters in new and interesting ways—ways that contribute to the quality of life for both us and others.

Recall that our basic purpose in engaging with ethics is to gain direction, insight, and guidance in moral matters. In Western philosophical tradition, this guidance and insight have traditionally taken the form of ethical theories. Furthermore, the three philosophical ethical perspectives we will consider are based on rational, systematic, and discursive thought processes, either implicitly or explicitly. As you might expect, there is no consensus among philosophers about the specific type of guidance and insight that ethics should provide, let alone which theory is best at supplying this help. Consequently, we will examine several ethical perspectives that exemplify diverse and distinct features.

The first type of ethical theory we will discuss is the Right-Action approach, followed by the Virtue Theory approach. For nearly two thousand years, Western philosophers followed the lead of ancient Greek thinkers, operating under the assumption that ethics should provide insight and guidance on the question of character. From this perspective, ethics should help us answer the question: What kind of person should we strive to be? Ethical theories of this sort are referred to as “Theories of Virtue.”

In the 17th century, moral philosophers took a different approach. Contrary to the ancient Greeks, these thinkers assumed that the fundamental insight and guidance ethics should provide concern questions of conduct. Ethics should help us determine what we ought or not do morally. From this perspective, the emphasis is placed on conduct rather than character.

Moral philosophies that adopt this approach are typically labeled as “Theories of Right Action.” We will begin our examination of ethical theory by looking at two classic theories of Right Action: Duty Ethics (Kantianism) and Utilitarianism.

These moral philosophies aim to provide direction on how we should conduct ourselves morally. Both approaches offer a “litmus test” to determine which forms of conduct are morally acceptable and which are not. However, there are crucial differences between the two theories of Right Action we will study, primarily concerning what makes some actions morally acceptable and others morally unacceptable. According to Utilitarianism, the consequences of actions have moral significance. In contrast, Duty Ethics maintains that the consequences of actions do not hold moral significance.

Practice Activity

Please read each multiple-choice question carefully and select the best answer from the options provided.

Immanuel Kant’s Deontological Ethics

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) made incredibly important contributions to every area of philosophical inquiry. However, given our time constraints and, more importantly, our specific interest as ethics students, our focus will be on his moral philosophy. Kant’s moral philosophy provides not only an account and method of testing for right action but also a fully developed account of genuine moral worth. Kant’s moral philosophy is often described as “deontological” because it pivots on the concept of duty. Furthermore, Kant’s approach combines a consideration of conduct with a concern for motives and intentions.

What Gives Actions Moral Worth?

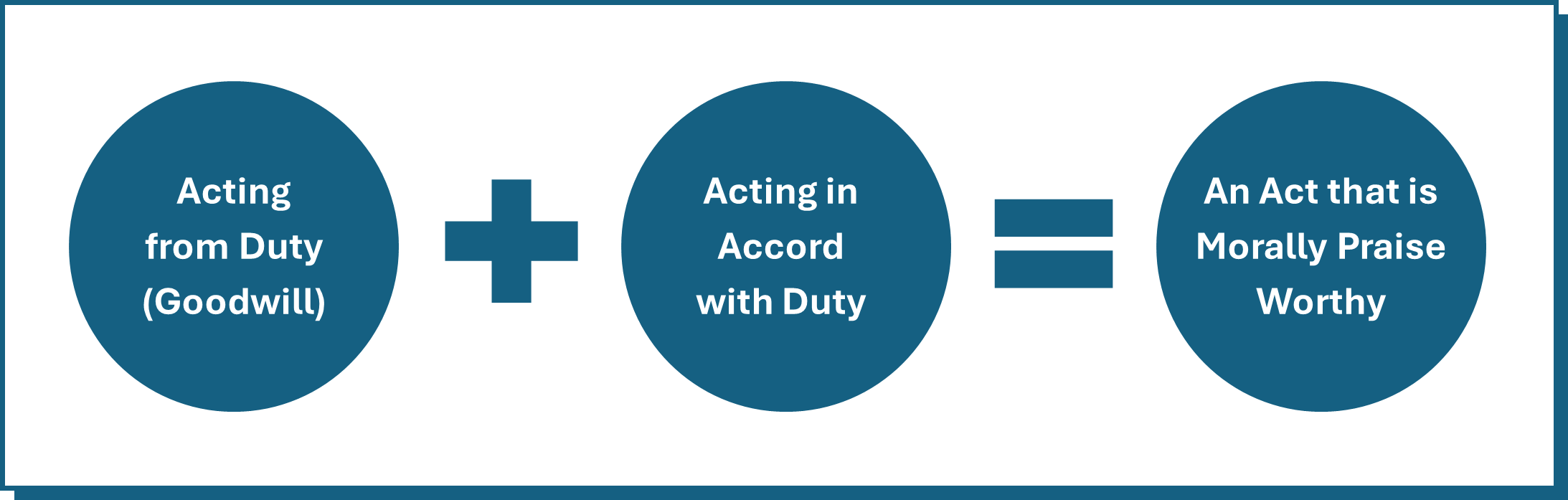

For an act to have genuine moral worth, Kant declared, two conditions must be met.

First, the act in question must be motivated by a sense of duty or goodwill. This means that the act is motivated by an intention to do the right thing simply because it is the right thing. According to Kant, being moved to act in morally acceptable ways by inclination, natural disposition, or even a desire to produce a desirable outcome lacks a necessary condition for conferring the maximum amount of moral worth on the conduct in question.

The second condition, which has already been alluded to, requires that the action in question must be morally right, or as Kant would say, it must be in accord with duty. Kant even went so far as to say that goodwill is the only thing that is intrinsically good, i.e., good in and of itself. Other goods, i.e., things we might value, are valuable only instrumentally.

Before proceeding to understand what Kant thought it meant to act in accord with duty—i.e., to do the right thing—let’s recap the ideas of his moral philosophy that have been advanced so far. What does Kant take “right action” to consist of? Answer: moral worth. What does Kant think gives an act moral worth? Answer: Acts are morally worthy if and only if they meet two conditions: 1) they are done from a sense of duty and 2) they are in accord with duty.

What Is the Right Thing to Do? (What Does It Mean to Act in Accord with Duty?)

So, what does Kant think is our duty? What does he think we, morally speaking, ought to do? The short answer is that Kant thought the right thing to do is to conduct ourselves in accordance with what he referred to as the Categorical Imperative. Think of the Categorical Imperative as Kant’s litmus test, which is predicated on his concept of persons as rational beings.

In fact, Kant formulated this test in at least three distinct ways or formulations. Kant explained that his intention in presenting the principle of morality in three different ways was simply to make the Categorical Imperative more intuitive (user-friendly). In other words, Kant claimed that the three modes were “equivalent,” meaning that an act subjected to one formulation of the Categorical Imperative would yield the same results if examined in light of one of the other formulations and vice versa. Likewise, a course of action that would fail one formulation of the Categorical Imperative would necessarily fail the other two as well. Alternatively, a course of action that passed one formulation of the Categorical Imperative would necessarily pass the other two as well.

To fully appreciate the concept of Kant’s Categorical Imperative, a couple of terminological points are in order. First, understand that imperatives are essentially commands.

Questions for Cogitation

Reflect on the sentences provided and identify which one’s express imperatives, or commands. Consider how each imperative influences behavior or action and think about why these directives might be important in ethical or moral contexts. Use your understanding of imperatives to guide your reflection.

Some of the sentences below express imperatives. Identify them.

- “So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you, for this sums up the Law and the Prophets.”

- “What time is it?”

- “Jenny’s phone number is 876-5309.”

- “Take good notes.”

- “You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.”

——————————————————————————————————————

Understanding Imperatives: Hypothetical and Categorical

Now that we have a basic understanding of imperatives—commands in general—it’s essential to recognize that Kant made a significant distinction among them. Some commands apply universally to everyone, while others do not. The former types are Categorical Imperatives, while the latter are Hypothetical Imperatives.

Hypothetical Imperatives

Kant defined moral duty in terms of Categorical Imperatives rather than Hypothetical Imperatives. Understanding the fundamental difference between these two types of commands is crucial for appreciating Kant’s ethical insights. Hypothetical Imperatives are commands, but their essential feature is that they are not ABSOLUTELY or UNIVERSALLY binding. In other words, they do not apply to everyone at all times. Instead, Hypothetical Imperatives are binding only for certain individuals and only under specific conditions.

Consider the following imperative:

(1) “Attend class, do your readings, and ask a lot of questions if you want to maximize your educational experience in PHIL 2306.”

Imperative (1) is binding but notice that it is binding only for individuals enrolled in PHIL 2306, and further, only for those who wish to maximize their educational experience in the course. Therefore, this imperative is not a Categorical Imperative because it does not apply universally. Some students might be content with merely fulfilling a degree requirement or earning a certain number of credits, without seeking to maximize educational value.

Categorical Imperatives

In contrast, Categorical Imperatives are commands that are absolutely and unconditionally binding. According to Kant, these imperatives are universal and apply to everyone. In fact, Kant posited that there is really only one Categorical Imperative: “Do your duty because it is your duty.”

Before delving deeper into Kant’s theory of Right Action, we need to understand his conception of persons or humanity. For Kant, a fundamental characteristic of persons is that they are RATIONAL. This is fitting since, in Kant’s view, morality is also rational. To say that persons are rational means they value logical consistency and coherence and reject contradictions and logical tensions of every sort.

Equally fundamental to Kant’s concept of persons is his claim that persons are ends in themselves, not mere means, or instruments. Unlike non-persons, persons have a say in what they do and how they are utilized. Kant expressed this by saying that persons are autonomous, meaning they should have control over their actions and how they are used. Because persons possess the quality of autonomy, Kant believed that morality demands they be respected.

Maxims and Kant’s Moral Philosophy

Before we explore Kant’s ideas about Right Action, it’s important to clarify a key term in his philosophy: “maxim.” A maxim is a statement that specifies a possible course of action in a particular situation. In Kant’s theory, maxims serve to contextualize moral problems, grounding his theory in practical scenarios.

Maxims essentially have the following form:

“Whenever I [or anyone] am in situation X, I will [or should] do Y.”

More Questions for Reflection

Consider again the five sentences referenced in the previous set of reflection questions. For those that express imperatives, determine whether the imperative expressed is a Hypothetical Imperative or a Categorical Imperative:

- “So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you, for this sums up the Law and the Prophets.”

- “What time is it?”

- “Jenny’s phone number is 876-5309.”

- “Take good notes.”

- “You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.”

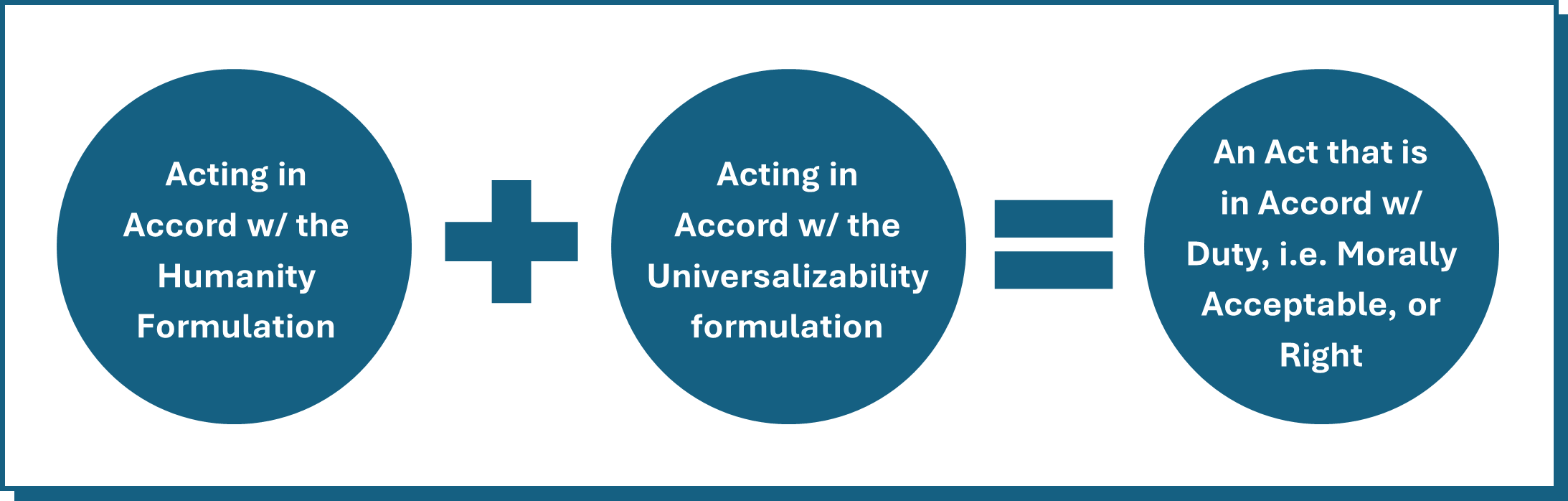

Duty: The Categorical Imperative

Let’s focus on Kant’s litmus test for genuine right action: Acting in Accord with Duty—the Categorical Imperative. For Kant, the moral law, or duty, is expressed in the Categorical Imperative. Moreover, Kant believed that the Categorical Imperative could be formulated in several different, yet equivalent, ways. In what follows, we will explore two of these formulations.

Friendly reminder: when studying the Cl, it is important to be mindful of Kant’s belief that all of the formulations of the Categorical Imperative are predicated upon the premises that like persons, morality is essentially RATIONAL.

The Universalizability Formulation

“Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”

Unique to the first formulation of the Categorical Imperative is the notion that actions which are in accord with duty will be the sort of actions that could be performed by one and all [without giving rise to any logical contradiction]. Put alternatively, this expression of the moral law tells us that in order for human conduct to be in accord with duty, it cannot, must not involve or presuppose any double standards. Conversely, if the universalization of some sort of conduct would involve or give rise to any contradiction, then it is certain that said conduct is in discord with duty, i.e. immoral.

The Humanity or “Respect-for-Persons” Formulation

“Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end.”

The second formulation turns on the notion that it is morally okay to “use” things, but not people. So that, any mode of conduct which involves the treatment of a person as if he/she was merely a thing or instrument is also in discord with duty, i.e. immoral.

Kant’s “Litmus Test” for Right Action: The Categorical Imperative in Action

The passages below illustrate Kant’s “litmus test” for Right Action, i.e., the Categorical Imperative in action. They demonstrate the “equivalence” of different formulations or “modes” of the Categorical Imperative. Both passages address the question of whether suicide is in accord with duty, using the maxim: “When things are going badly and one is in deep despair, commit suicide.”

Carefully consider the passages below.

Note that in Passage (1), Kant evaluates the maxim according to the first formulation or mode of the Categorical Imperative—the Universalizability Formulation.

In Passage (2), Kant uses the second mode or formulation of the Categorical Imperative—the Humanity Formulation.

Passage 1

Suicide: A man reduced to despair by a series of misfortune feels wearied of life but is still so far in possession of his reason that he can ask himself whether it would not be contrary to his duty to himself to take his own life. Now he inquires whether the maxim of his action could become a universal law of nature. His maxim is: “From self-love I adopt it as a principle to shorten my life when its longer duration is likely to bring more evil than satisfaction. “It is asked then simply whether this principle founded on self-love can become a universal law of nature. Now we see at once that a system of nature of which it should be a law to destroy life by means of the very feeling whose special nature it is to impel to the improvement of life would contradict itself and, therefore, could not exist as a system of nature; hence that maxim cannot possibly exist as a universal law of nature and, consequently, would be wholly inconsistent with the supreme principle of all duty.

Passage 2

Suicide: He who contemplates suicide should ask himself whether his action can be consistent with the idea of humanity as an end in itself. If he destroys himself in order to escape from painful circumstances, he uses a person merely as a mean to maintain a tolerable condition up to the end of life. But a man is not a thing, that is to say, something which can be used merely as means, but must in all his actions be always considered as an end in himself. I cannot, therefore, dispose in any way of a man in my own person so as to mutilate him, to damage or kill him.

Notice that the two formulations yielded the same test results: taking one’s own life is NOT IN ACCORD WITH DUTY. Kant believed that these examples illustrate how the different formulations of the Categorical Imperative are, indeed, equivalent.

Questions for Cogitation

Below are two passages where Kant uses one of the formulations of his Categorical Imperative to test for right action. For each passage, identify the formulation being used: the Universalizability Formulation or the Humanity Formulation.

-

- One finds himself forced by necessity to borrow money. He knows that he will not be able to repay it but sees also that nothing will be lent to him unless he promises stoutly to repay it in a definite time. He desires to make this promise, but he has still so much conscience as to ask himself: ”ls it not unlawful and inconsistent with duty to get out o fa difficulty in this way?” Suppose however that he resolves to do so: then the maxim of this action would be expressed thus: “When I think myself in want of money, I will borrow money and promise to repay it, although I know that I never can do so.” Now this principle of self-love or of one’s own advantage may perhaps be consistent with my whole future welfare; but the question now is, “Is it right?” I change then the suggestion of self-love into a universal law, and state the question thus: “How would it be if my maxim were a universal law?” Then I see at once that it could never hold as a universal law of nature but would necessarily contradict itself. For supposing it to be a universal law that everyone when he thinks himself in a difficulty should be able to promise whatever he pleases, with the purpose o f not keeping his promise, the promise itself would become impossible, as well as the end that one might have in view in it, since no one would consider that anything was promised to him, but would ridicule all such statements as vain pretenses.

- The Humanity Formulation

- The Universalizability Formulation

- One finds in himself a talent which with the help of some culture might make him a useful man in many respects. But he finds himself in comfortable circumstances and prefers to indulge in pleasure rather than to take pains in enlarging and improving his happy natural capacities. He asks, however, whether his maxim of neglect of his natural gifts, besides agreeing with his inclination to indulgence, agrees also with what is called duty. He sees then that a system of nature could indeed subsist with such a universal law although men (like the South Sea islanders) should let their talents rest and resolve to devote their lives merely to idleness, amusement, and propagation of their species- in a word, to enjoyment; but he cannot possibly will that this should be a universal law of nature, or be implanted in us as such by a natural instinct. For, as a rational being, he necessarily wills that his faculties be developed, since they serve him and have been given him, for all sorts of possible purposes.

- The Humanity Formulation

- The Universalizability Formulation

- One finds himself forced by necessity to borrow money. He knows that he will not be able to repay it but sees also that nothing will be lent to him unless he promises stoutly to repay it in a definite time. He desires to make this promise, but he has still so much conscience as to ask himself: ”ls it not unlawful and inconsistent with duty to get out o fa difficulty in this way?” Suppose however that he resolves to do so: then the maxim of this action would be expressed thus: “When I think myself in want of money, I will borrow money and promise to repay it, although I know that I never can do so.” Now this principle of self-love or of one’s own advantage may perhaps be consistent with my whole future welfare; but the question now is, “Is it right?” I change then the suggestion of self-love into a universal law, and state the question thus: “How would it be if my maxim were a universal law?” Then I see at once that it could never hold as a universal law of nature but would necessarily contradict itself. For supposing it to be a universal law that everyone when he thinks himself in a difficulty should be able to promise whatever he pleases, with the purpose o f not keeping his promise, the promise itself would become impossible, as well as the end that one might have in view in it, since no one would consider that anything was promised to him, but would ridicule all such statements as vain pretenses.