6.3 Memory

Questions to consider:

- How does working memory work, exactly?

- What is the difference between working and short-term memory?

- How does long-term memory function?

- What obstacles exist to remembering?

Memory is one of those cherished but mysterious elements in life. Everyone has memories, and some people are very good at rapid recall, which is an enviable skill for test takers. We know that we seem to lose the capacity to remember things as we age, and scientists continue to study how we remember some things but not others and what memory means, but we do not know that much about memory, really.

Nelson Cowan is one researcher who is working to explain what we do know about memory. His article “What Are the Differences between Long-Term, Short-Term, and Working Memory?” breaks down the different types of memory and what happens when we recall thoughts and ideas. When we remember something, we actually do quite a lot of thinking.

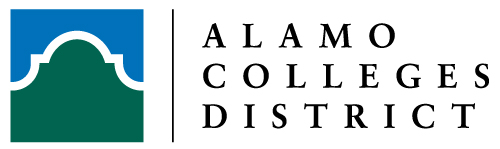

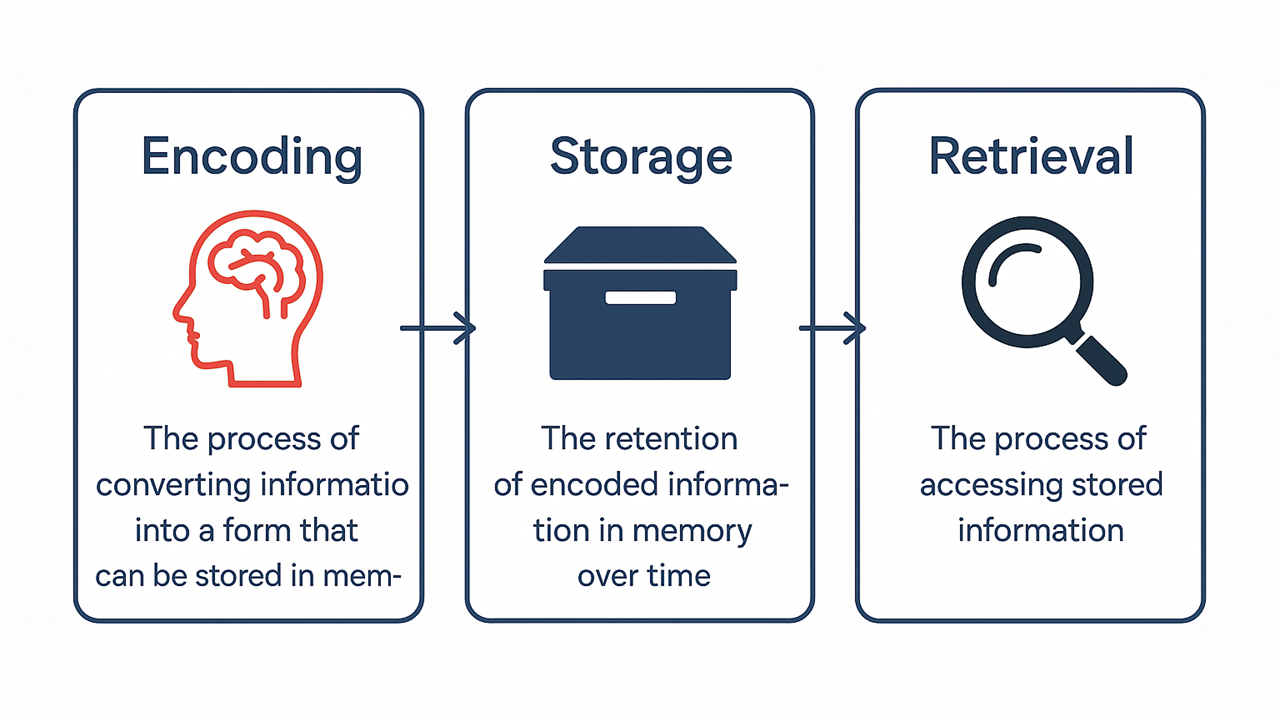

We go through three basic steps when we remember ideas or images: we encode, store, and retrieve that information.

Encoding

Encoding is how we first perceive information through our senses, such as when we smell a lovely flower or a putrid trash bin. Both make an impression on our minds through our sense of smell and probably our vision. Our brains encode, or label, this content in short-term memory in case we want to think about it again.

Storage

If the information is important and we have frequent exposure to it, the brain will store it for us in case we need to use it in the future in our aptly named long-term memory.

Retrieval

Later, the brain will allow us to recall or retrieve that image, feeling, or information so we can do something with it. This is what we call remembering.

Analysis Question

Analysis Question

Take a few minutes to list ways you create memories on a daily basis. Do you think about how you make memories? Do you do anything that helps you keep track of your memories?

Foundations of Memory

William Sumrall et al. in the International Journal of Humanities and Social Science explain the foundation of memory by noting: “Memory is a term applied to numerous biological devices by which living organisms acquire, retain, and make use of skills and knowledge. It is present in all forms of higher order animals. The most evolutionary forms of memory have taken place in human beings. Despite much research and exploration, a complete understanding of human memory does not exist.”

Working Memory

Working memory is a type of short-term memory that we use when we are actively performing a task. For example, nursing student Marilyn needs to use her knowledge of chemical reactions to suggest appropriate prescriptions in various medical case studies. She does not have to recall every single fact she learned in years of chemistry classes, but she does need to have a working memory of certain chemicals and how they work with others. To ensure she can make these connections, Marilyn will have to review and study the relevant chemical details for the types of drug interactions she will recommend in the case studies.

In working memory, you have access to whatever information you have stored in your memory that helps you complete the task you are performing. For instance, when you begin to study an assignment, you certainly need to read the directions, but you must also remember that in class your professor reduced the number of problems the written instructions indicated you needed to finish. This was an oral addition to the written assignment. The change to the instructions is what you bring up in working memory when you complete the assignment.

Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory is a very handy thing. It helps us remember where we set our keys or where we left off on a project the day before. Think about all the aids we employ to help us with short-term memory: you may hang your keys in a particular place each evening, so you know exactly where they are supposed to be. When you go grocery shopping, do you ever choose a product because you recall an advertising jingle? If that memory causes you to buy that product, the advertising worked. We help our memory along all the time. In fact, we can modify these everyday examples of memory assistance for purposes of studying and test taking.

Activity 6.3

Consider this list of items. Look at the list for no more than 30 seconds. Then, on a sheet of paper, without looking at the list, write down as many items as you can remember.

| Items | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseball | Picture frame | Tissue | Paper clip |

| Bread | Pair of dice | Fingernail polish | Spoon |

| Marble | Leaf | Doll | Scissors |

| Cup | Jar of sand | Deck of cards | Ring |

| Blanket | Ice | Marker | String |

Now, look back at your list and make sure that you give yourself credit for any words that you got right. Any items that you misremembered, meaning they were not in the original list, you won’t count in your total. TOTAL ITEMS REMEMBERED _______________________.

There were 20 total items. Did you remember between 5 and 9 items? If you did, then you have a typical short-term memory and you just participated in an experiment, of sorts, to prove it.

Harvard psychology professor George A. Miller in 1956 claimed humans can recall about five to nine (7 +/-2) bits of information in our short-term memory at any given time. Other research has come after this claim, but this concept is a popular one. Miller’s article is entitled “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two.”

Considering the vast amount of knowledge available to us, five to nine bits isn’t very much to work with. To combat this limitation, we clump information together, making connections to help us stretch our capacity to remember. Many factors play into how much we can remember and how we do it, including the subject matter, how familiar we are with the ideas, and how interested we are in the topic, but we certainly cannot remember absolutely everything.

Activity 6.4

Now, let’s revisit the items above. Go back to them and see if you can organize them in a way that you would have about five groups of items. See below for an example of how to group them.

Row 1: Items found in a kitchen

Row 2: Items that a child would play with

Row 3: Items of nature

Row 4: Items in a desk drawer/school supplies

Row 5: Items found in a bedroom

| Items | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cup | Spoon | Ice | Bread | |

| Baseball | Marble | Pair of dice | Doll | Deck of cards |

| Jar of sand | Leaf | |||

| Marker | String | Scissors | Paper clip | |

| Ring | Picture frame | Fingernail polish | Tissue | Blanket |

Now that you have grouped items into categories, also known as chunking, you can work on remembering the categories and the items that fit into those categories, which will result in remembering more items. Check it out below by covering up the list of items again and writing down what you can remember.

Look back at your list and make sure that you give yourself credit for any that you got right. Any items that you misremembered, meaning they were not in the original list, you won’t count in your total. TOTAL ITEMS REMEMBERED _______________________. Did you increase how many items you could remember?

Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory is exactly what it sounds like. These are things you recall from the past, such as the smell of your elementary school cafeteria or how to pop a wheelie on a bicycle. Our brain keeps a vast array of information, images, and sensory experiences in long-term memory. Whatever it is we are trying to keep in our memories, whether a beautiful song or a list of chemistry vocabulary terms, must first come into our brains in short-term memory. If we want these fleeting ideas to transfer into long-term memory, we must do some work, such as having frequent exposure to the information over time (such as studying the terms every day for a period or the repetition you performed to memorize multiplication tables or spelling rules).

According to Alison Preston of the University of Texas at Austin’s Center for Learning and Memory, “A short-term memory’s conversion to a long-term memory requires changes within the brain . . . and result[s] in changes to neurons (nerve cells) or sets of neurons. For example, new synapses—the connections between neurons through which they exchange information—can form to allow for communication between new networks of neurons. Alternatively, existing synapses can be strengthened to allow for increased sensitivity in the communication between two neurons.”

We learn the lyrics of a favorite song by singing and/or playing the song over and over. That alone may not be enough to get that song into the coveted long-term memory area of our brain, but if we have an emotional connection to the song, such as a painful breakup or a life-changing proposal that occurred while we were listening to the song, this may help. Think of ways to make your study session memorable and create connections with the information you need to study. That way, you have a better chance of keeping your study material in your memory so you can access it whenever you need it.

Obstacles to Remembering

If remembering things we need to know for exams or for learning new disciplines were easy, no one would have problems with it, but students face several significant obstacles to remembering, including a persistent lack of sleep and an unrealistic reliance on cramming. Life is busy and stressful for all students, so you have to keep practicing strategies to help you study and remember successfully, but you also must be mindful of obstacles to remembering.

Lack of Sleep

Let’s face it, sleep and college do not always go well together. You have so much to do! All that reading, all those papers, all those extra hours in the science lab or tutoring center or library! And then we have the social and emotional aspects of going to school. When you consider everything you need to attend to in college, you probably will not be surprised that sleep is often the first thing we give up as we search for more time to accomplish everything we are trying to do. That seems reasonable—just wake up an hour earlier or stay up a little later. But you may want to reconsider picking away at your precious sleep time.

If you cannot focus well because you did not get enough sleep, then you likely will not be able to remember whatever it is you need to recall for any sort of studying or test-taking situation. Most exams in a college setting go beyond simple memorization, but you still have a lot to remember for exams. For example, when Saanvi sits down to take an exam on introductory biology, she needs to recall all the subject-specific vocabulary she read in the textbook’s opening chapters, the general connections she made between biological studies and other scientific fields, and any biology details introduced in the unit for which she is taking the exam.

Trying to make these mental connections on too little sleep will take a large mental toll because Saanvi has to concentrate even harder than she would with adequate sleep. She is not merely tired; her brain is not refreshed and primed to conduct difficult tasks. Although not an exact comparison, think about when you overtax a computer by opening too many programs simultaneously. Sometimes the programs are sluggish or slow to respond. Your body is a bit like that on too little sleep.

On the flip side, though, your brain on adequate sleep is amazing, and sleep can actually assist you in making connections, remembering difficult concepts, and studying for exams. The exact reasons for this are still a serious research project for scientists, but the results all point to a solid connection between sleep and cognitive performance.

Analysis Question

Analysis Question

How long do you sleep every night on average? Do you see a change in your ability to function when you haven’t had enough sleep? What could you do to limit the number of nights with too little sleep?

Downside of Cramming

At least once in their college careers, most students will experience the well-known pastime called cramming. See if any of this is familiar: Shelley has lots of classes, works part-time at a popular restaurant, and is just amazingly busy, so she puts off serious study sessions day after day. She is not worried because she has set aside time she would have spent sleeping to cram just before the exam. That is the idea anyway. Originally, she planned to stay up a little late and study for four hours from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. and still get several hours of refreshing sleep. But it is Dolphin Week or Beat State Day or whatever else comes up, and her study session does not start until midnight—she will pull an all-nighter. So, two hours after her original start time, she tries to cram all the lessons, problems, and information from the last two weeks of lessons into this one session. Shelley falls asleep around 3 a.m. with her notes and books still on her bed. After her late night, she does not sleep well and goes into the morning exam tired. Shelley does OK but not great on the exam, and she is not pleased with her results. More and more research indicates that the stress Shelley has put on her body doing this, combined with the way our brains work, makes cramming a seriously poor choice for learning.

Your brain simply refuses to cooperate with cramming—it sounds like a good idea, but it does not work. Cramming causes stress, which can lead to paralyzing test anxiety; it erroneously supposes you can remember and understand something fully after only minimal exposure; and it overloads your brain, which, however amazing it is, can only focus on one concept at a time and a limited number of concepts.

Leading neuroscientist John Medina claims that the brain begins to wander at about 10 minutes, at which point you need a new stimulus to spark interest. That does not mean you cannot focus for longer than 10 minutes; you just need to switch gears a lot to keep your brain engaged. Have you ever heard a speaker drone on about one concept for, say, 30 minutes without somehow changing pace to engage the listeners? It does not take much to re-engage—pausing to ask the listeners questions or moving to a different location in the room will do it—but without these subtle attention markers, listeners start thinking of something else. The same thing happens to you if you try to cram all reading, problem-solving, and note reviewing into one long session; your brain will wander.

Quick Quiz 6.3

- What are some ways you convert short term memories into long term memories?

- Do your memorization strategies differ for specific courses (e.g. how do you remember for math or history?)

Licenses and Attribution

CC Licensed Content

- College Success by Amy Baldwin is licensed CC BY. Access for free.

- Psychology by Rose M. Spielman is licensed CC BY. Access for free.

References

- Abel, M., & Bäuml, K.-H. T. (2013). Sleep can reduce proactive interference. Memory, 22(4), 332–339. doi:10.1080/09658211.2013.785570. Retrieved from http://www.psychologie.uni-regensburg.de/Baeuml/papers_in_press/sleepPI.pdf

- Bellezza, F. S. (1981). Mnemonic devices: Classification, characteristics and criteria. Review of Educational Research, 51, 247–275.

- Bodie, G. D., Powers, W. G., & Fitch-Hauser, M. (2006). Chunking, priming, and active learning: Toward an innovative approach to teaching communication-related skills. Interactive Learning Environment, 14(2), 119–135.

- Craik, F. I. M., & Watkins, M. J. (1973). The role of rehearsal in short-term memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12, 599–607.

- Learning to learn. (n.d.). OER Commons. https://oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/73880/overview?section=4

Images or Graphic Elements

- Images used by permission from Alamo Colleges District Department of Communications.