2.4 Conducting Research

Questions to consider:

- What are the parts of a research study in a peer-reviewed journal article?

- How should you read a peer-reviewed article?

Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

Peer-reviewed journal articles (PRJA’s) are some of the most reliable resources you can use for your academic research. However, you can also use these strategies when evaluating other types of scholarly sources, such as books. Although the sections of books and articles are labeled differently, they generally serve the same purpose. These sections can provide information and structure to help you quickly evaluate the source. For example, the summary section at the beginning of an article is called the abstract, but in a book, this is called the introduction. However, they are labeled, you can use the information found within each section to evaluate the source.

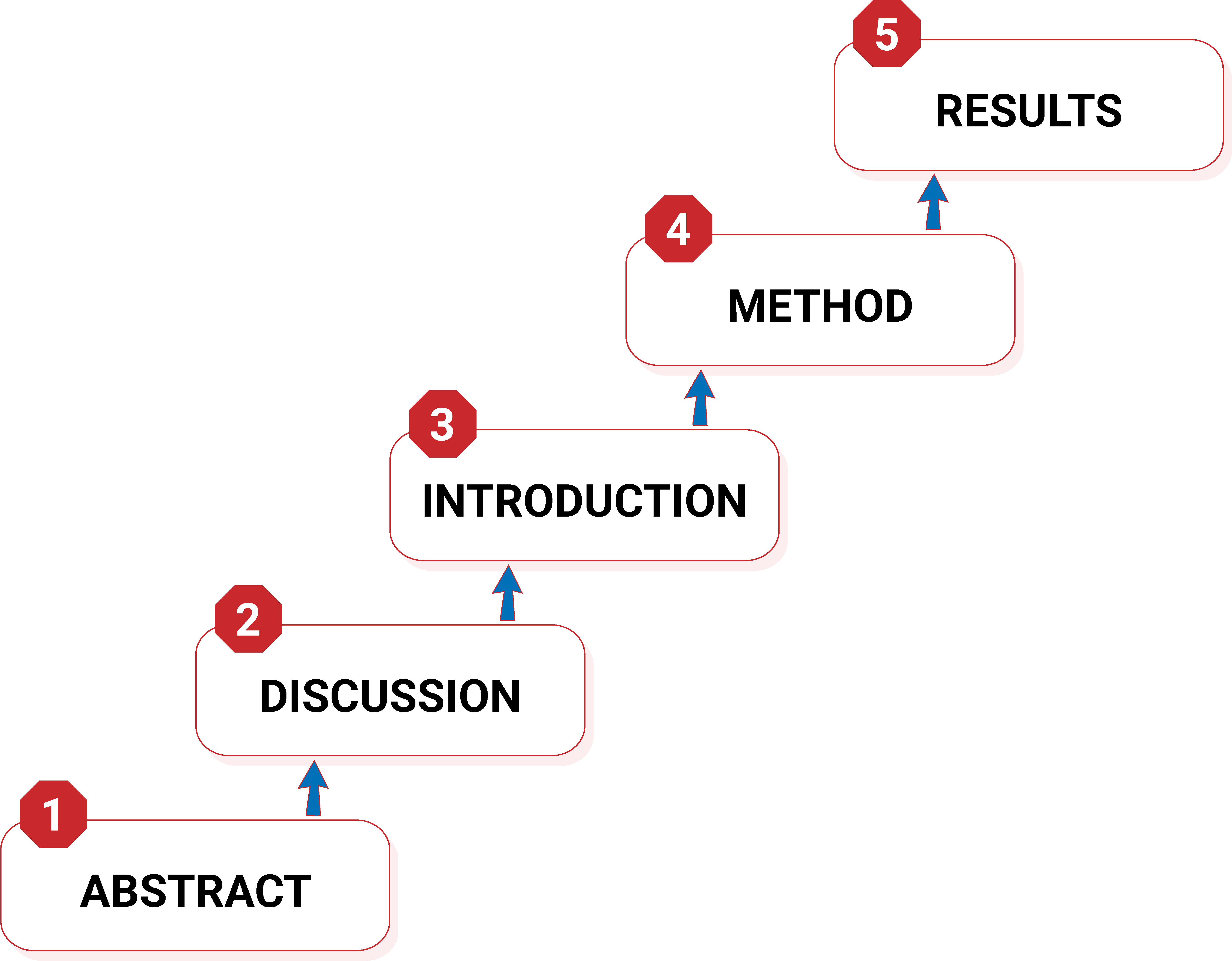

The following chart illustrates what to expect in each section of a peer-reviewed journal article.

Table 2.2 Parts of a Peer-Reviewed Journal Article

|

Abstract |

|

|---|

|

Introduction |

|

|---|

|

Method |

|

|---|

|

Results |

|

|---|

|

Discussion |

|

|---|

How to Read a Peer-Reviewed Journal Article

If an article has an abstract, read that first. The abstract is a summary of the entire article. This summary gives you a general idea of what the authors were trying to accomplish, as well as a brief description of their experiment, observations, or analysis. If the abstract is too complex or technical, that is an indication for what the rest of the article will be like. If you can understand most of the language used in the abstract, highlight terms that you don’t recognize to look up later. This can be a useful learning experience. However, if you can’t understand the article at all, then it may not be the right resource for you, even if it’s written by the foremost expert in the field.

Once you have read the abstract, you can skip down to the discussion section. With scholarly articles, you don’t always have to read straight through from start to finish. Strategically skipping around and skimming specific sections can help you understand the big takeaways from the research. The discussion usually includes information about major findings and why the author thinks they are important. By reading the discussion, you can verify that the impression you got from the abstract is correct and check that the article is actually relevant for your research question.

Order to Read Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

Explore the Rest of the Article

If you found the abstract and discussion relevant for your research topic, continue to read the rest of the article. This will give the details that you will want to use and cite in your work.

Next, read the introduction. This section will help you understand why the researcher decided to conduct this study. It will also give an overview of what other research has already been conducted on this topic.

Last, dig into the methods and results sections. The methods section describes how the author(s) conducted their research, including who the subjects were, how the researchers gathered their data (e.g. surveys, interviews, experiments, or observations) and why they chose that method. Be on alert for approaches that are too general or don’t give any detail, such as only stating “We ran a qualitative analysis.” If you don’t understand a term or phrase, take note of it to look it up later. Reviewing an article’s methods can give you a deeper understanding of how the authors got their results and will put their findings into a better context.

The results section provides specific details about what the authors found. This includes descriptions of overall results and their corresponding data. Important or notable findings may be pulled out in tables, figures, and graphics, to help you understand the data more quickly or completely. Reading the results section will give you the full breadth of the research findings, not just the highlights you saw in the discussion.

Validity and Credibility

Before you move on to interpreting your data and addressing the significance of what you found, you need to understand the concepts of validity and credibility. Validity and credibility refer to the quality of information. In research, validity asks if the information is logical, sound, or well-grounded. Credibility refers to the information being trustworthy. This could involve a certain conclusion, an entire concept, or even how something was measured in a research study. Is the information logical, or justifiable when considering the real world? Does this conclusion make sense? Does the information sound true? Can the information be trusted? When considering research studies, the question is often, did the researchers effectively measure what was trying to be measured? For college students, this is where critical thinking can be practiced.

There are many ways you can check the validity of a piece of information. Can you find contradictory or confirmatory data? Can you find evidence that disputes what you are reading? If so, use this information. It is always useful to mention opposing ideas. Ultimately, doing so might strengthen your own ideas. Is the topic within the expertise of the person offering the information? Was the method chosen to convey this information the best method to use? The credibility of the author is another important aspect of checking your sources. In other words, evaluate the authors. Are they experts on the topic? Do they have credentials to write on this particular topic? Has this author written anything else on this topic?

Finally, consider when your source was published. This date can affect how useful (or not) that source will be for you now. Depending on your topic or assignment, you may need something published within the last five or ten years. This can be the case when researching recent events or technological innovations. For other topics, it may be necessary to consult an older source, such as for research on a historical event or a longstanding theory in your discipline. Keep in mind, if a theory has been around for a long time, it has had more opportunity to be criticized, overturned, built upon, or reinforced. You may need to seek out newer sources about the same topic to figure out whether the information in your original source is outdated today.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Web Search Engines

The internet presents its own challenges when it comes to discovering valid and credible information. When looking at a website, you should be able to answer the following questions: Who is responsible for the site (i.e., who is the author)? What can you find out about the responsible party? Where does the site’s information come from (e.g., opinions, facts, documents, quotes, excerpts)? For certain topics and types of information, you may need to dig deeper. Take into account the funding behind a website. Look up the author, and see if they have written anything else and if there are any obvious biases present in that writing. What are the key concepts, issues, and “facts” on the site? And finally, can the key elements of the site be verified by another site or source? In other words, if you want to find some information online, you shouldn’t just Google the topic and then depend on the first website that pops up.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

|

|

Activity 2.3

Reflect on what bias the following sites may have. Without consulting the internet, write one to two sentences on what ideas the following organizations may present. After you consider these on your own, conduct a search and see if you were accurate in your assumptions about the entities.

- National Dairy Council

- Yoga Society

- People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA)

- The American Medical Association

Whatever you write or declare based on sources should be correct and truthful. Reliable sources present current and honest information backed up with evidence you can check. Any source that essentially says you should believe this “because I said so” isn’t a valid source for critically thinking, information-literate individuals.

Finding Sources for Your Research Needs

Every search has a different context. Sometimes you just need basic facts and news. In that case, Google would be a good option. However, if you need scholarly information, Google is probably not your best choice. For most academic work, google is not enough.

The San Antonio College Library provides students 24/7 access to these sources in the form of academic research databases. Personalized research help via online chat, email, text messaging, phone, online meeting, and in-person is also, available through the San Antonio College Library.

Evaluating Information

Vast amounts of new information are created every minute and it can be overwhelming to make sense of it all. How do you know you’ve found the best information for your needs? You evaluate it! In this section, we’ll discuss how you can more effectively evaluate and fact-check all kinds of information, from news stories to academic articles.

Evaluating information is something you do every day, whether you know it or not. You evaluate information when you determine what to write down in your notes, debate issues with friends, or look up new movie reviews. All this is done before you even start gathering information for a research project.

Evaluating Using the CRAAP Test

When you begin evaluating sources, what should you consider? The CRAAP test is a series of common criteria you can use to evaluate the Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose of your sources. The CRAAP test was developed by librarians at California State University at Chico and it gives you a good, overall set of elements to look for when evaluating a resource. Let’s consider what each of these evaluative elements means.

Currency

One of the most important and interesting steps to take as you begin researching a subject is selecting the resources that will help you build your thesis and support your assertions. Certain topics require you to pay special attention to how current your resource is—because they are time sensitive, because they have evolved so much over the years, or because new research comes out on the topic so frequently. When evaluating the currency of an article, consider the following:

- When was the item written, and how frequently does the publication come out?

- Is there evidence of newly added or updated information in the item?

- If the information is dated, is it still suitable for your topic?

Relevance

Understanding what resources are most applicable to your subject and why they are applicable can help you focus and refine your thesis. Many topics are broad and searching for information on them produces a wide range of resources. Narrowing your topic and focusing on resources specific to your needs can help reduce the piles of information and help you focus on what is truly important to read and reference. When determining relevance consider the following:

- Does the item contain information relevant to your argument or thesis?

- Does the information presented support or refute your ideas?

- What is the material’s intended audience?

- Is the information at an appropriate level (not too basic or advanced for your needs)?

Authority

Understanding more about your who wrote the source helps you determine when, how, and where to use that information. When determining the authority of your source, consider the following:

- Is your author an expert on the subject?

- What is the author or information producer’s background?

- What affiliations does the author have? Could these affiliations affect their position?

- What organization or body published the information? Is it authoritative? Does it have an explicit position or bias?

Accuracy

Determining where information comes from, if the evidence supports the information, and if the information has been reviewed can help you decide how and whether to use a source. When determining the accuracy of a source, consider the following:

- Is the source well-documented? Does it include footnotes, citations, or a bibliography?

- Is information in the source presented as fact, opinion, or propaganda? Are biases clear?

- Can you verify information from the references cited in the source?

- Has the information been reviewed and edited for errors?

Purpose

Knowing why the information was created is a key to evaluation. Understanding the reason or purpose of the information, if the information has clear intentions, or if the information is fact, opinion, or propaganda will help you decide how and why to use information:

- Is the author’s purpose to inform, sell, persuade, or entertain clear?

- Is the information fact, opinion, or propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

When you feel overwhelmed by the information you are finding, the CRAAP test can help you determine which information is the most useful to your research topic. How you respond to what you find out using the CRAAP test will depend on your topic. Maybe you want to use two overtly biased resources to inform an overview of typical arguments in a particular field. Perhaps your topic is historical and currency means the past hundred years rather than the past one or two years. Use the CRAAP test, be knowledgeable about your topic, and you will be on your way to evaluating information efficiently and well!

Quick Quiz 2.4

- What are the parts of a peer-reviewed journal article?

- What is the most efficient order to read the parts of a peer-reviewed journal article?

- How do you evaluate whether you should use a particular source in your work?

Licenses and Attribution

CC Licensed Content

- College Success by Amy Baldwin is licensed CC BY. Access for free.

References

- Kestler, U., and Kwantlen Polytechnic University Library. Academic Integrity. Press Books, 2020, https://www.oercommons.org/courses/academic-integrity/view#.

- Iowa State University Library Instruction Services. Library 160: Introduction to College-Level Research. Iowa State University Digital Press, 2021, https://dx.doi.org/10.31274/isudp.2021.72.

- “OERTX.” Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, https://oertx.highered.texas.gov/courseware/lesson/2609/overview.

- Springer Open. (n.d.). [Screenshot of a database search from Fire Ecology]. Fire Ecology. https://fireecology.springeropen.com

- “Student Guide to AI.” www.studentguidetoAI.org.

Images or Graphic Elements

- Images used by permission from Alamo Colleges District Department of Communications.