3.2 Your Map to Success: The Career Planning Cycle

Questions to consider:

- What steps should I take to learn about my best opportunities?

- What can I do to prepare for my career while in college?

- What experiences and resources can help me in my search?

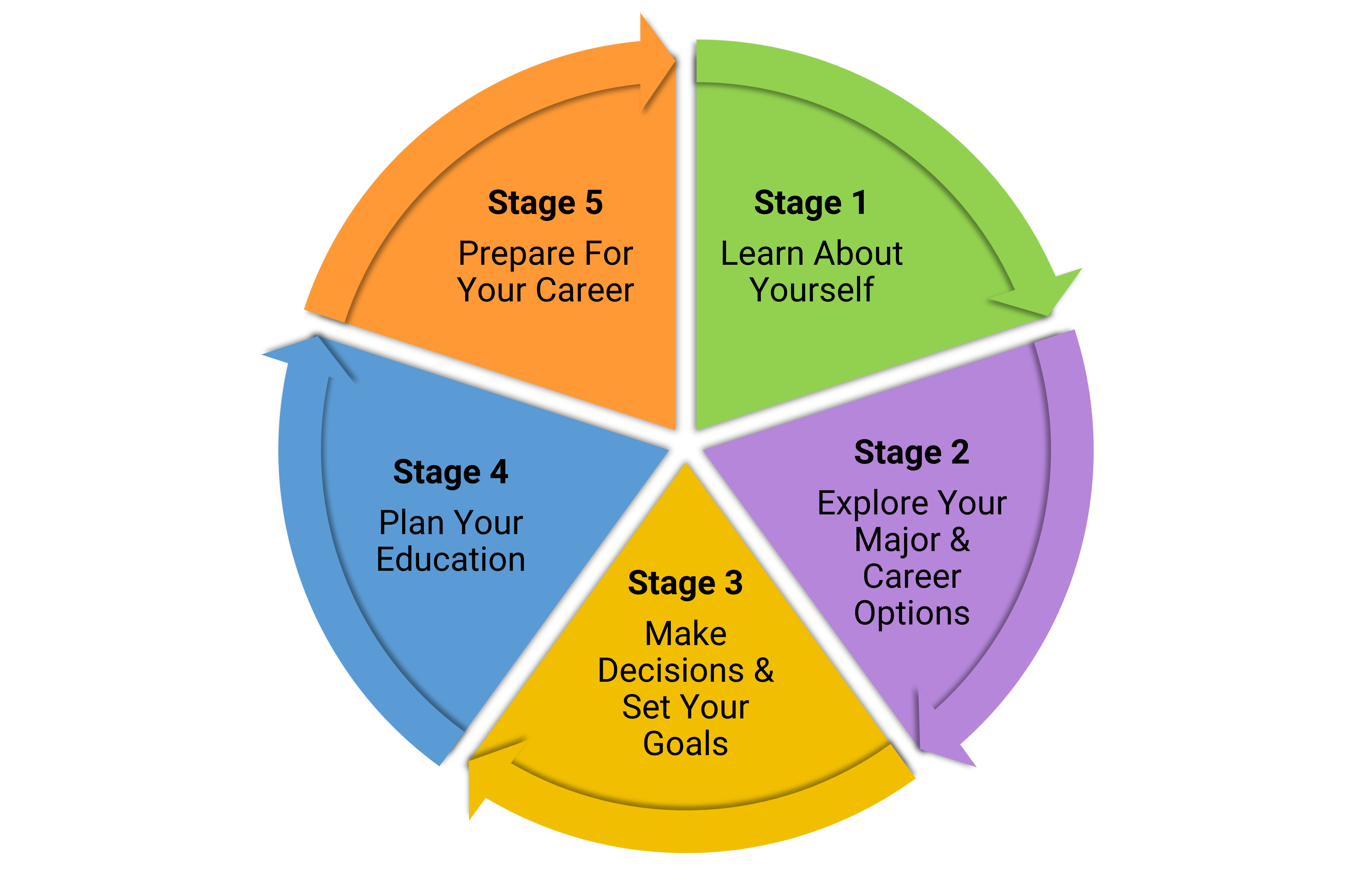

The Career Planning Cycle helps us apply some concrete steps to figure out where we might fit into the work world. If you follow these steps, you will learn about who you truly are, as well as who you can be as a working professional. Let’s look at each of the steps in the Career Planning Cycle in more detail.

Stage 1 – Learn About Yourself

To understand what type of work suits us and to be able to convey that to others to get hired, we must become experts in knowing who we are. Gaining self-knowledge is a lifelong process, and college is the perfect time to gain and adapt to this fundamental information. Following are some of the types of information that we should have about ourselves:

- Interests: Things that we like and want to know more about. These often take the form of ideas, information, knowledge, and topics.

- Skills/Aptitudes: Things that we either do well or can do well. These can be natural or learned and are usually skills—things we can demonstrate in some way. Some of our skills are “hard” skills, which are specific to jobs and/or tasks. Others are “soft” skills, which are personality traits and/or interpersonal skills that accompany us from position to position.

- Values: Things that we believe in. Frequently, these are conditions and principles.

- Personality: Things that combine to make each of us distinctive. Often, this shows in the way we present ourselves to the world. Aspects of personality are customarily described as qualities, features, thoughts, and behaviors.

In addition to knowing the things we can and like to do, we must also know how well we do them. What are our strengths? When employers hire us, they hire us to do something, to contribute to their organization in some way. We get paid for what we know, what we can do, and how well or deeply we can demonstrate these things. Think of these as your Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities (KSAs). As working people, we can each think of ourselves as carrying a “tool kit.” In our tool kit are the KSAs that we bring to each work.

Awareness of the need to develop your career identity and your vocational worth is the first step. Next, undertaking a process that is mindful and systematic can help guide you through. Often, career assessment is of great assistance in increasing your self-knowledge. It is most often designed to help you gain insight more objectively. You may want to think of an assessment as pulling information out of you and helping you put it together in a way that applies to your career. There are two main types of assessments: formal assessments and informal assessments.

Formal Assessments

Formal assessments are typically referred to as “career inventories.” It is important to use assessments that are developed to be reliable and valid. Look to your career center for their recommendations; their staff have often spent a good deal of time selecting instruments that they believe work best for students.

Here are some commonly used and useful assessments that you may come across:

- Interest Assessments: Strong Interest Inventory, Self-Directed Search, Campbell Interest and Skill Survey, Harrington-O’Shea Career Decision-Making System

- Personality Measures: Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, CliftonStrengths (formerly StrengthsQuest), Big Five Inventory, Keirsey Temperament Sorter, TypeFocus, DiSC

- Career Planning Software: SIGI 3, FOCUS 2

Informal Assessments

Often, asking questions and seeking answers can help get us information that we need. When we start working consciously on learning more about any subject, things that we never considered may become apparent. Happily, this applies to self-knowledge as well. Some things that you can do outside of career testing to learn more about yourself can include:

Self-Reflection:

- Notice when you do something that you enjoy or that you did particularly well. What did that feel like? What about it made you feel positive? Is it something that you would like to do again? What impact did you make through your actions?

- Most people are the “go to” person for something. What do you find that people come to you for? Are you good with advice? Do you tend to be a good listener, observing first and then speaking your mind? Do people appreciate your repair skills? Are you good with numbers? What role do you play in a group?

Enlist Others:

- Ask people who know you to tell you what they think your strengths are. What kinds of things have they observed you doing well? What personal qualities do you have that they value?

- Find a mentor—such as a professor, an alum, an advisor, or a community leader—from whom you think you could learn new things. Many of your college faculty likely have (or had) other roles and positions.

- Get involved with one or more activities on campus that will let you use skills outside of the classroom. You will be able to learn more about how you work with a group and try new things that will add to your skill set.

No single assessment can tell you exactly what career is right for you; the answers to your career questions are not in a test. The reality of career planning is that it is a discovery process that uses many methods over time to strengthen our career knowledge and belief in ourselves.

Stage 2 – Explore Jobs and Careers

Many students seem to believe that the most important decision they will make in college is to choose their major. While this is an important decision, even more important is to determine the type of knowledge you would like to have, understand what you value, and learn how you can apply this in the workplace after you graduate. For example, if you know you like to help people, this is a value. If you also know that you are interested in math and/or finances, you might study to be an accountant. To combine both, you would gain as much knowledge as you can about financial systems and personal financial habits so that you can provide greater support and better help to your clients.

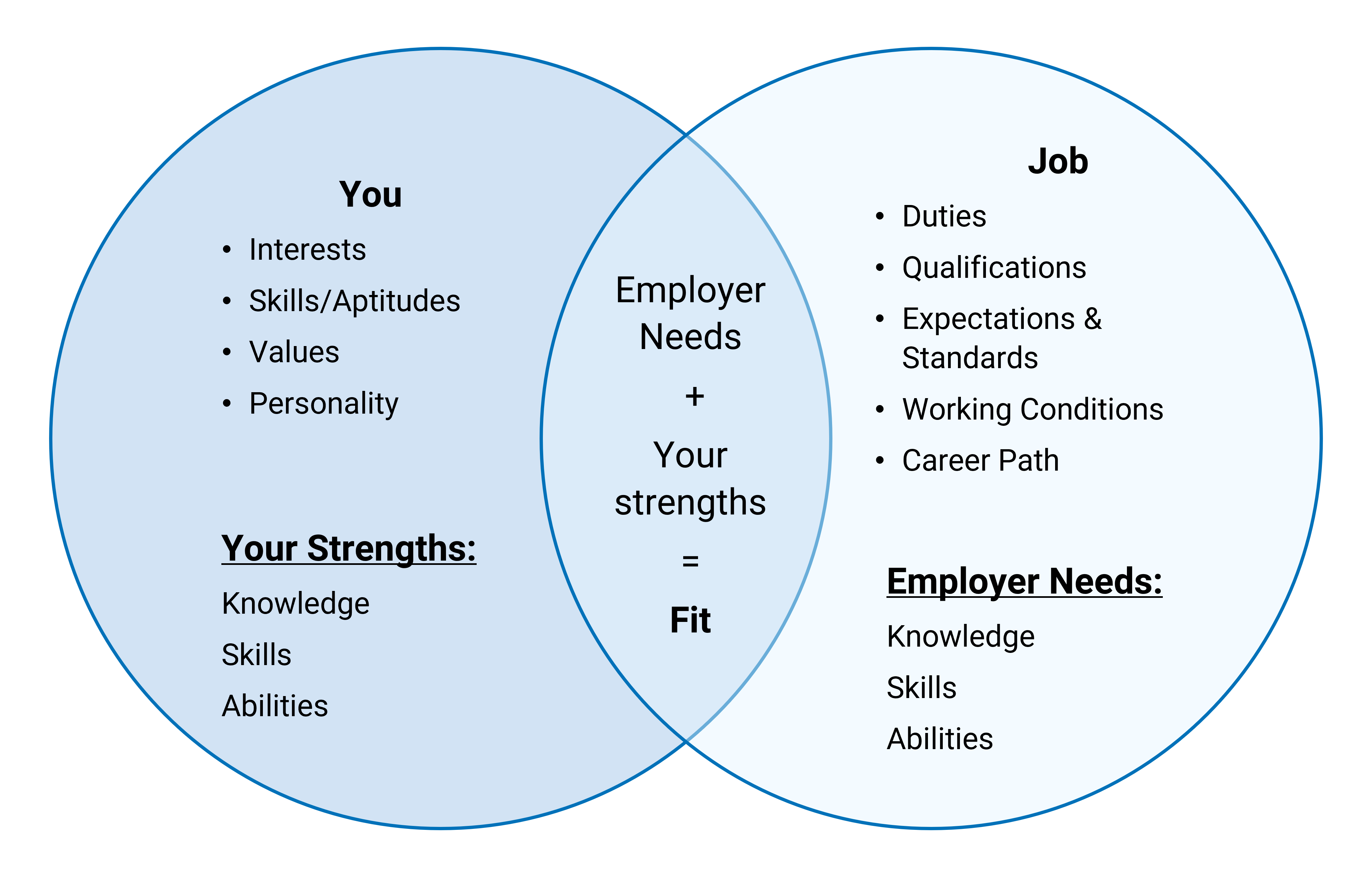

The four factors of self-knowledge (interests, skills/aptitudes, values, and personality), which manifest in your Knowledge, Skills, Abilities (KSAs), are also the factors on which employers evaluate your suitability for their positions. They consider what you can bring to their organization that is in line with their organization’s standards and needs.

Along with this, each job has KSAs that define it. You may think about finding a job/career as you look at the figure below.

The importance of finding the right fit cannot be overstated. Many people do not realize that the KSAs of the person and the requirements of the job must match to get hired in a given field. What is even more important, though, is that when a particular job fits your four factors of self-knowledge and maximizes your KSAs, you are most likely to be satisfied with your work! The “fit” works to help you not only get the job but also enjoy the job.

So, if you work to learn about yourself, what do you need to know about jobs, and how do you learn it? In our diagram, if you need to have self-knowledge to determine the YOU factors, then to determine the JOB factors, you need to have workplace knowledge. This involves understanding what employers in the workplace and specific jobs require. Aspects of workplace knowledge include:

- Labor Market Information: Economic conditions, including supply and demand of jobs; types of industries in a geographic area or market; regional sociopolitical conditions and/or geographic attributes.

- Industry Details: Industry characteristics; trends and opportunities for both industry and employers; standards and expectations.

- Work Roles: Characteristics and duties of specific jobs and work roles; knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to perform the work; training and education required; certifications or licenses; compensation; promotion and career path; hiring process.

This “research” may sound a little dry and uninteresting at first but consider it as a look into your future. If you are excited about what you are learning and your career prospects, learning about the places where you may put all your hard work into practice should also be exciting! Most professionals spend many hours not only performing their work but also physically being located at work. For something that is such a large part of your life, it will help you to know what you are getting into as you get closer to realizing your goals.

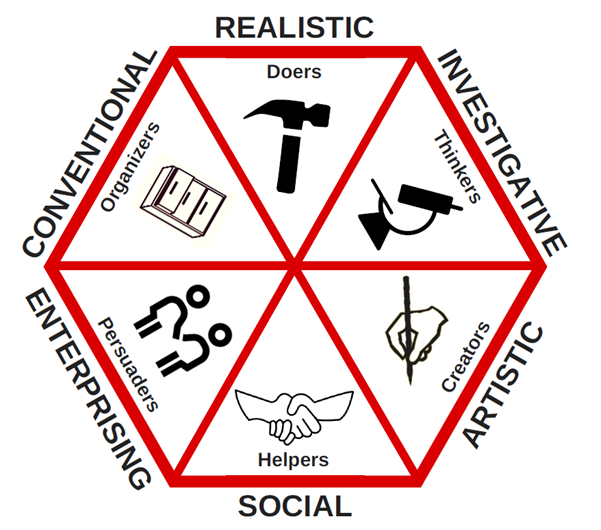

Holland’s Theory of Career Choice

Careers are categorized using interest areas. If a career utilizes your highest interests, you are more likely to feel that the career is a good fit for you. Listed below are the six Holland Occupational Interest Types. The descriptions of “pure types” will rarely be an exact fit for any one person. Your interest profile will more likely combine several types to varying degrees.

Realistic (R)

These people describe themselves as honest, loyal, and practical. They are doers more than thinkers. They have strong mechanical, motor, and athletic abilities; like the outdoors; and prefer working with machines, tools, plants, and animals.

Investigative (I)

These people love problem solving and analytical skills. They are intellectually stimulated and often mathematically or scientifically inclined; like to observe, learn, and evaluate; prefer working alone; and are reserved.

Artistic (A)

These people are the “free spirits.” They are creative, emotional, intuitive, and idealistic; have a flair for communicating ideas; dislike structure and prefer working independently; and like to sing, write, act, paint, and think creatively. They are like the investigative type but are interested in the artistic and aesthetic aspects of things more than the scientific.

Social (S)

These are “people” people. They are friendly and outgoing; love to help others, make a difference, or both; have strong verbal and personal skills and teaching abilities; and are less likely to engage in intellectual or physical activity.

Enterprising (E)

These people are confident, assertive risk takers. They are sociable; enjoy speaking and leadership; like to persuade rather than guide; like to use their influence; have strong interpersonal skills; and are status conscious.

Conventional (C)

These people are dependable, detail oriented, disciplined, precise, persistent, and practical; value order; and are good at clerical and numerical tasks. They work well with people and data, so they are good organizers, schedulers, and project managers.

Since many career guidance tests are based on Holland’s work, let us take a closer look at what careers are matched with the different types. Just as many individuals have more than one personality type, many jobs show a strong correlation to more than one occupational type.

|

Realistic

|

|

|

|---|

|

Investigative

|

|

|

|---|

|

Artistic

|

|

|

|---|

|

Social

|

|

|

|---|

|

Enterprising

|

|

|

|---|

|

Conventional

|

|

|

|---|

Table 3.1 Occupational Options by Type

Research careers using resources provided by the Department of Labor. Two excellent Career Exploration Websites are the U.S Bureau of Labor and Statistics and O*NET Online.

Read online information that is relevant to the professions you are interested in. Good sources for this include professional associations. Just “googling” information is risky. Look for professional and credible information. The Occupational Outlook Handbook has links to many of these sources. Your academic advisor, the Career Readiness & Experiential Opportunities Office (CREO), and your academic department can also guide you. CREO can provide resume review, interviewing tips, internships, and job search assistance.

Something to keep in mind as you make choices about your major and career is that the training is not the job. What you learn in your college courses is often foundational information; it provides basic knowledge that you need for more complex concepts and tasks. For example, a second-year student who is a premedical student has the interests and qualities that may make her a good physician, but she is struggling to pass basic chemistry. She starts to think that medical school is no longer an appropriate goal because she does not enjoy chemistry. Does it make sense to abandon a suitable career path because of one course? In some ways, yes. In medical school, the education is so long and intensive that if the student cannot persevere through one introductory course, she may not be determined to complete the training. On the other hand, if you are truly dedicated to your path, do not let one difficult course deter you.

Shantelle

The example above describes Shantelle. They were not quite sure which major to choose, and they were feeling pressure because the window for making their decision was closing. They considered their values and strengths—they love helping people and have always wanted to pursue work in medical training. As described above, Shantelle struggled in general chemistry this semester and found that they did not enjoy it at all. They have heard nightmare stories about organic chemistry being even harder. Simultaneously, Shantelle is taking Intro to Psychology, something they thought would be an easier course but that they enjoy even though it is challenging. Much to their surprise, they found the scientific applications of theory in the various types of mental illness utterly fascinating. But given that their life dream was to be a physician, Shantelle was reluctant to give up on medicine because of one measly chemistry course. With the help of an advisor, Shantelle decided to postpone choosing a major for one more semester and take a course in clinical psychology. Since there are so many science courses required for premed studies, Shantelle also agreed to take another science course. Their advisor helped Shantelle realize that it was probably not a wise choice to make such an important decision based on one course experience.

Stage 3 – Focus Your Path

When you know yourself and know what to expect from a workplace and a job, you have information to begin to make decisions. As we have discussed throughout this book, you are not attending college solely to get a job. But this is likely one of your goals, and your time in school offers a tremendous opportunity to both prepare for your career (or careers) and make yourself more attractive to organizations where you want to work. Successfully learning the content of your classes and earning good grades are among the most important. Beyond these priorities, you will learn the most about yourself and your potential career path if you engage in activities that will help you make decisions. Simply sitting back and thinking about the decision does not always help you take action.

Take advantage of every resource you can while in college. Your college has a wealth of departments, programs, and people dedicated to your success. The more you work to discover and engage with these groups, the more successfully you’ll establish networks of support and build skills and knowledge for your career. Make plans to drop by SAC’s Student Enrichment Center which offers career services. There, you will learn about events you can attend, and you will get to know some of the people there who can help you.

Stage 4 – Try Things Out

In the first two steps of the Career Planning Cycle, you gather information. You may have some ideas about jobs and careers that you may like, but you also may wonder if you will really like them. How will you know? How can you be more certain? It is a great idea to try out a new skill or career field before you commit to it fully. Experience helps you become more qualified for positions. One exciting aspect of college is that there is a huge variety of learning experiences and activities in which to get involved. The following are some ways that you can try things out and get experience.

Community Involvement, Volunteering, and Clubs

You are in college to develop yourself as an individual. You will gain personally satisfying and enriching experience by becoming more involved with your college or general community. Organizations, clubs, and charities often rely on college students because of their motivation, knowledge, and increasing maturity. The work can increase your skills and abilities, providing valuable experience that will lead to positive results. Participating in Phi Theta Kappa Honor Society and volunteering can be an important way to access a profession and get a sense for if you will enjoy it.

Once you join a club or related organization, take the time to learn about their leadership opportunities. Most campus clubs have some type of management structure—treasurer, vice president, president, and so on. You may “move up the ranks” naturally, or you may need to apply or even run for election. Some organizations, such as a campus newspaper, radio station, or dance team, have skill-based semi-professional roles such as advertising manager, sound engineer, or choreographer. These opportunities may not always be available to you as a first-year student, but you can take on shorter-term roles to build your skills and make a bigger impact. Managing a fundraiser, planning an event, or temporarily taking on a role while someone else is busy are all ways to engage further.

Internships and Experiential Learning

Many employers value experience as much as they do education. Internships and similar fieldwork allow you to use what you have learned and, sometimes more importantly, see how things work “in the real world.” These experiences drive you to communicate with others in your field and help you understand the day-to-day challenges and opportunities of people working in similar areas. Even if the internship is not at a company or organization directly in your field of study, you will focus on gaining transferable skills that you can apply later.

When you are an intern, you are usually treated like you work there full-time. It is not just learning about the job; it is doing the job, much like an entry-level employee. The level of commitment may vary by the type of internship and may be negotiable based on your schedule. Be clear about what is required and what you can handle given your other commitments, because you want to leave a particularly good impression. (Internship managers are your top resource for employment references and letters of recommendation.)

Internship and Experiential Learning Terminology

| Internship | A period of work experience in a professional organization, in which participants (interns) are exposed to and perform some of the tasks of actual employees. Internships are usually a high commitment and may be paid and/or result in college credit. |

|---|---|

| Externship/Job Shadowing | Usually a briefer and lower-commitment experience than internships, in which participants are observing work activities and undertaking small projects. Unpaid and not credit-bearing. |

| Fieldwork | A period or trip to conduct research or participate in the “natural environment” of a discipline or profession. Fieldwork may involve visiting a work site, such as a hospital or nursing home, or being a part of a team gathering data or information. |

| Apprenticeship | A defined period of on-the-job training in which the student is formally doing the job and learning specific skills. Unlike most internships, apprenticeships are usually formal requirements to attain a license or gain employment in skilled trades, and they are growing in use in health care, IT, transportation, and logistics. |

| Undergraduate Research | Even as an undergraduate, you may find opportunities to participate in actual research in your field of study. Colleges often have strict guidelines on types and levels of participation, and you will likely need to apply. The benefits include firsthand knowledge of a core academic activity and exposure to more people in your field. |

| Related Employment | It may be possible to get a regular, low-level paying job directly in your field of study or in a related place of work. While it is not essential, simply being around the profession will prepare and inform you better. |

| Clinicals, Student Teaching, and Related Experiences | Health care, education, and other fields often have specific requirements for clinicals (learning experience in health care facilities) or student teaching. These are often components of the major and required for both graduation and licensure. |

| Service Learning | Students learn educational standards through tackling real-life problems in their community. Involvement could be hands-on, such as working in a homeless shelter. Students could also tackle broad issues indirectly, such as by solving a local environmental problem. |

Gain Transferable (Marketable) Skills

Through your coursework, campus involvement, job, networking, and internships you should focus as much as possible on building and improving transferable skills. These are abilities and knowledge useful across many industries, job types, and roles. They can be transferred—hence the name—from where you learned them to another career or area of study.

Some examples of transferable skills include communication, leadership, teamwork, computation/quantitative literacy, information technology, research/analysis, and foreign languages. Employers believe that transferable skills are critical to the success of their recent college graduate new hires. The top four career competencies that employers want are critical thinking/problem solving, teamwork/collaboration, professionalism/work ethic, and oral/written communication.

These are considered skills because they are not simply traits or personality elements; they are abilities and intelligences you can develop and improve. Even if you are a great writer before starting an internship, you may need to learn how to write in a more professional manner—becoming more succinct, learning the executive summary, conforming to templates, and so on. Once you establish that skill, you can not only mention it on a resume or an interview, but also discuss the process by which you improved, demonstrating your adaptability and eagerness to learn.

Not everyone can land an internship or perform fieldwork. Perhaps you need to work full-time while in school. If so, focus on developing transferable skills in that environment. Take on new challenges in areas where you do not have experience. For example, if you work in retail, ask your manager if you can help with inventory or bookkeeping (building quantitative literacy skills). If you are a waiter, help the catering manager plan a party or order food (building organizational skills). Remember, extending yourself in this way is not simply a means to enhance your resume. By taking on these new challenges, you will see a side of the business you did not have before and learn things that you can apply in other situations.

Now that you have explored career options for yourself, we will now look at other ways you can prepare yourself for moving into your career.

Stage 5 – What to Do to Get Ready

Being prepared to find a job means putting evidence of your Knowledge-Skills-Abilities (KSAs) together in a way that employers will understand. It is one thing to say you can do something; it is another to show that you can. The following are things that you will want to compile as a part of your college career.

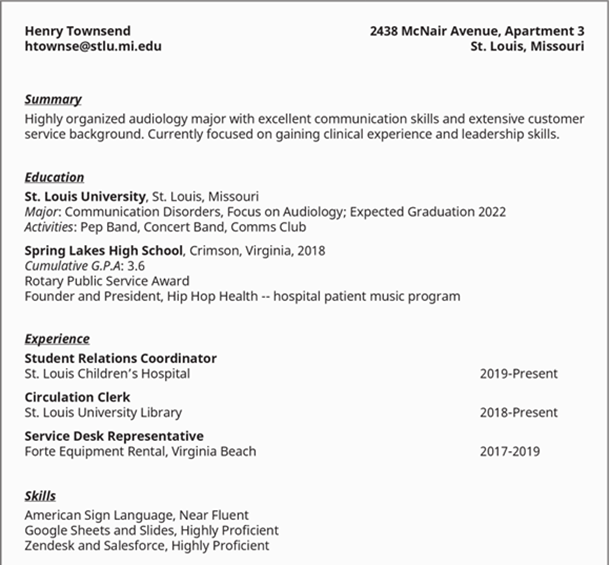

Resumes and Profiles: The College Version

You may already have a resume or a similar profile (such as LinkedIn), or you may be thinking about developing one. Usually, these resources are not required for early college studies, but you may need them for internships, work-study, or other opportunities. When it comes to an online profile, be very careful and intentional when developing it.

Resume

A resume is a summary of your education, experience, and other accomplishments. It is not simply a list of what you have done; it is a showcase that presents the best you have to offer for a specific role.

A resume is a one-page summary (two, if you are a more experienced person) that generally includes the following information:

- Name and contact information

- Objective and/or summary

- Education—all degrees and relevant certifications or licenses

- While in college, you may list coursework closely related to the job to which you are applying.

- Work or work-related experience—usually in reverse chronological order, starting with the most recent and working backward. (Some resumes are organized by subject/skills rather than chronologically.)

- Career-related/academic awards or similar accomplishments

- Specific work-related skills

While you are in college, especially if you went into college directly after high school, you may not have formal degrees or significant work experience to share. That is okay. Tailor the résumé to the position for which you are applying, and include high school academic, extracurricular, and community-based experience. These show your ability to make a positive contribution and are a good indicator of your work ethic.

Digital Profiles

An online profile is becoming a standard component of professional job seeking and networking. LinkedIn is a networking website used by people from nearly every profession. It combines elements of résumés and portfolios with social media. Users can view, connect, communicate, post events and articles, comment, and recommend others. Some professions or industries have specific LinkedIn groups or subnetworks. Other professions or industries may have their own networking sites, to be used instead of or in addition to LinkedIn.

As a college student, it might be a great idea to have a LinkedIn or related profile. It can help you make connections in a prospective field and provide access to publications and posts on topics that interest you. Before you join and develop a public professional profile, however, keep the following in mind:

- Be professional.

- Add relevant experience and information as you attain it.

- Professional networking is different from social media. While LinkedIn has a strong social media component, users are often annoyed by too much nonprofessional sharing.

- LinkedIn is not a replacement for a real resume.

Social Media and Online Activity Never Go Away

It is important to remember that future employers, educational institutions, internship coordinators, and others can see most of what you have posted or done online. Companies are well within their rights to dig through your social media pages, and those of your friends or groups you are a part of, to learn about you. Tasteless posts, inappropriate memes, harassment, pictures or videos of high-risk behavior, and even aggressive and mean comments are all problematic. They may convince a potential employer that you are not right for their organization. Be careful of who and what you retweet, like, and share. It is all traceable, and it can all have consequences.

Building Your ePortfolio

Future employers or educational institutions may want to see the work you have done during school. Also, you may need to recall projects or papers you wrote to remember details about your studies. Your ePortfolio can be one of your most important resources.

Items to include an ePortfolio:

- Evidence of any workshops or special classes you attended. Include a certificate, registration letter, or something else indicating you attended/completed it.

- Evidence of volunteer work, including a write-up of your experience and how it impacted you.

- Related experience and work products from your time prior to college.

- Materials associated with career-related talks, performances, debates, or competitions that you delivered or took part in.

- Products, projects, or experiences developed in internships, fieldwork, clinicals, or other experiences (see below).

- Evidence of “universal” workplace skills such as computer abilities or communication, or specialized abilities such as computation/number crunching.

- Projects, simulations, and case studies.

Preparing for an Informational Interview

Throughout this section, we have discussed how important relationships are to your career development. Meeting with someone in your specific career field can be a great way to gain insight into the pros and cons of that position. Conducting this type of information interview can sometimes be a little intimidating but with preparation and understanding, these encounters can be not only helpful but also rewarding. Here are some ideas to consider when meeting new people who can be helpful to your career:

- Be yourself. You are your own best asset. If you are comfortable with who you are and where you come from, others will be, too.

- Be polite, not too casual. If your goal is to become a professional, look and sound the part.

- Listen.

- Think of some questions ahead of time.

- Say thank you. No need to go on and on but thank them for any advice they give or simply for taking the time to talk with you.

Letters of Recommendation

Letters of recommendation are often a standard component of convincing people you are the right person to join their organization. Some positions or institutions require a certain quantity of letters and may have specific guidance on who should write them.

Whom should I ask for a letter? They are usually written by instructors, department chairs, club advisors, managers, coaches, and others with whom you have had a good relationship. Maybe it is someone who taught two or three of your courses, or someone you helped in a volunteer or work-study capacity.

How to ask? Be straightforward and direct. They may ask you to provide more information about yourself so that they can write an original letter. If they do so, be thorough but prompt—you do not want to keep them waiting. And if you have a deadline, tell them.

Thank-you notes. They wrote you a letter, so you should write them one in return.

Stage 6 – Steps to Success

A key to success is the ability to manage change, adapt to the unexpected, and handle setbacks. This is also true as you work through the Career Planning Cycle. While this ability may be difficult during the process, it will build a better—and more employable—you. While you cannot prepare for every obstacle or surprise, you can be certain that you will encounter them.

You may go through all of college, and even high school, with one job in mind. You may apply early to a specific program, successfully complete all the requirements, and set yourself on a certain career path. And then something may change.

As described above, changes in your interests or goals are a natural part of developing your career; they are nothing to be ashamed of. Most college students change majors several times. Even once they graduate, many people find themselves enjoying careers they did not envision. Ask the people around you, and many will share stories about how they took a meandering or circuitous path to their profession. Some people end up in jobs or companies that they did not know existed when they started school. Be open to returning to any of the steps in the cycle as circumstances change.

Quick Quiz 3.2

- What is the difference between a formal and informal assessment?

- What are transferable skills?

Licenses and Attribution

CC Licensed Content

- College Success by Amy Baldwin is licensed CC BY. Access for free.

References

- August, L. (n.d.). Figure 3.2: The Career Planning Cycle [Figure]. (Based on work by Lisa August).

- COD Newsroom. (n.d.). Career fair [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/codnewsroom/

- US Embassy Jerusalem. (n.d.). Two women in conversation discussing documents [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usembassyjlm/

Images or Graphic Elements

- Images used by permission from Alamo Colleges District Department of Communications.