5.1 Learning Theory

Metacognition is one of the distinctive characteristics of the human mind that enables us to reflect on our own mental states. It is defined as “thinking about thinking.” Metacognition is reflected in many day-to-day activities, such as when you realize that one strategy is better than another for solving a particular type of problem, or when you are able to recognize how your own experiences and perspectives may impact how you understand, react to, or judge certain situations.

Metacognition includes two clusters of activities: knowledge about cognition and regulation of cognition. Metacognitive knowledge refers to a person’s knowledge or understanding of cognitive processes. In other words, it is the ability to think about what you know and how you know it. This includes knowledge about your own strengths and limitations as well as factors that may interact to help or hinder your learning. Metacognitive regulation builds on this knowledge and refers to a person’s ability to regulate cognitive processes during problem-solving. You use metacognitive knowledge to make decisions about how to approach new problems or how to effectively learn new information and skills. This involves using various self-regulatory mechanisms like planning ahead, monitoring your progress, and evaluating your own efficiency and effectiveness in learning a task.

To give a concrete example of these metacognitive activities, let’s apply them to how you study for an exam. Knowing that your cell phone’s notifications tend to distract you from studying is an example of metacognitive knowledge: you are aware of your phone’s potential to hinder your learning. Metacognitive regulation requires you to take action based on this knowledge and would involve you making the conscious decision to put your cell phone where you cannot see or hear it or to turn it off completely, while you study. In doing so, you regulate your use of your phone to help yourself be more successful in preparing for your exam.

Stages of the Learning Process

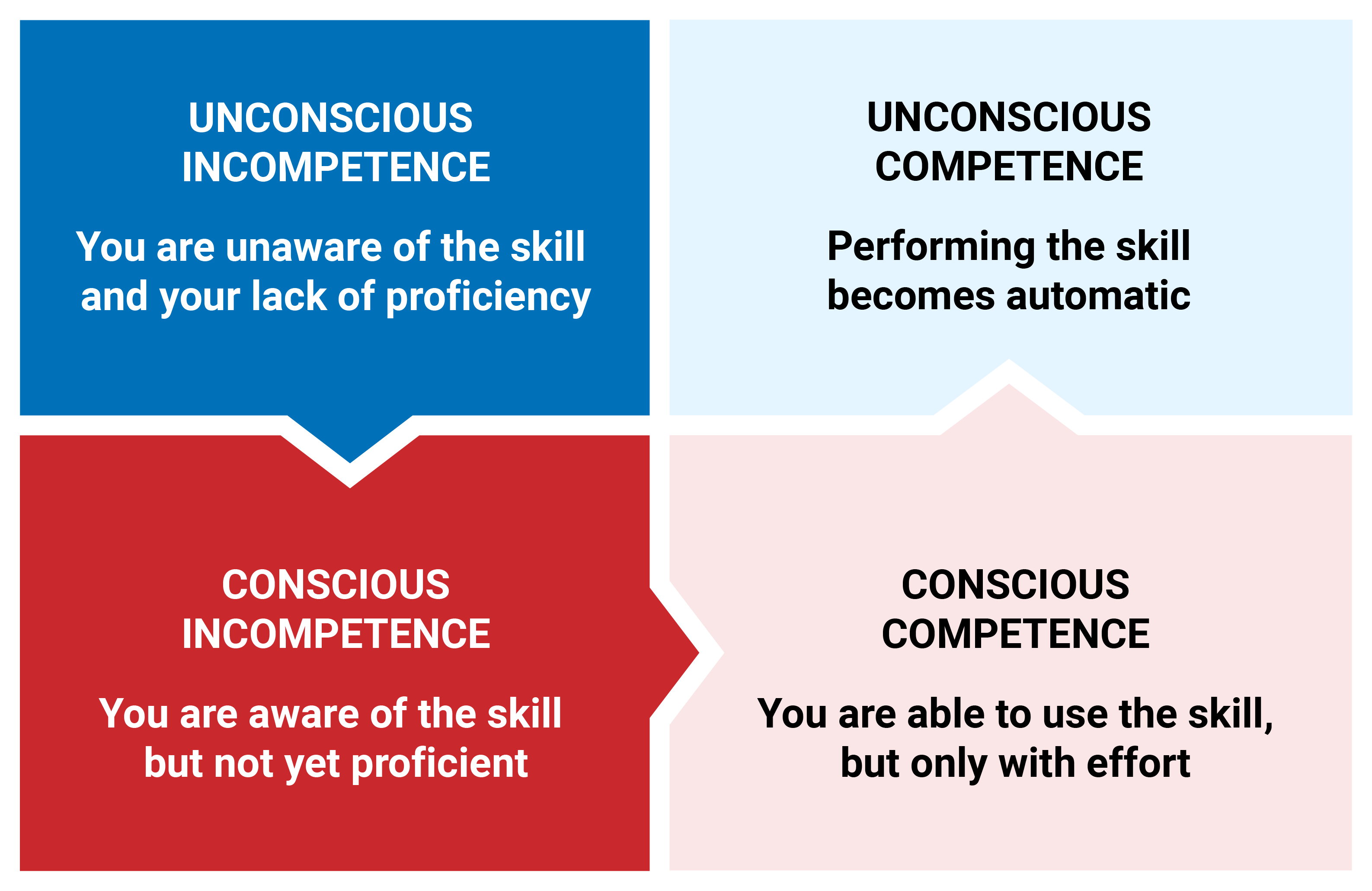

We said earlier that metacognitive knowledge involves thinking about the cognitive process, about what you know and how you know it. An important first step in developing metacognitive knowledge about yourself as a learner is to develop an awareness of how we learn new things. Consider the experiences you have had with learning something new, such as learning to tie your shoes or drive a car. You probably began by showing interest in the process, and after some struggling, it became second nature. These experiences were all part of the learning process, which can be described in four stages:

Unconscious incompetence

This will likely be the easiest learning stage—you don’t know what you don’t know yet. During this stage, a learner mainly shows interest in something or prepares for learning. For example, if you wanted to learn how to dance, you might watch a video, talk to an instructor, or sign up for a future class. Stage 1 might not take long.

Conscious incompetence

This stage can be the most difficult for learners because you begin to register how much you need to learn—you know what you don’t know. This is metacognition at work! Think about the saying “It’s easier said than done.” In stage 1 the learner only has to discuss or show interest in a new experience, but in stage 2, they begin to apply new skills that contribute to reaching the learning goal. In the dance example above, you would now be learning basic dance steps. Successful completion of this stage relies on practice.

Conscious competence

You are beginning to master some parts of the learning goal and are feeling some confidence about what you do know. For example, you might now be able to complete basic dance steps with few mistakes and without your instructor reminding you how to do them. Stage 3 requires skill repetition, and metacognition helps you identify where to focus your efforts.

Unconscious competence

This is the final stage in which learners have successfully practiced and repeated the process they learned so many times that they can do it almost without thinking. At this point in your dancing, you might be able to apply your dance skills to a freestyle dance routine that you create yourself. However, to feel you are a “master” of a particular skill by the time you reach stage 4, you still need to practice constantly and reevaluate which stage you are in so you can keep learning. For example, if you now felt confident in basic dance skills and could perform your own dance routine, perhaps you’d want to explore other kinds of dance, such as tango or swing. That would return you to stage 1 or 2, but you might progress through the stages more quickly this time since you have already acquired some basic dance skills.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

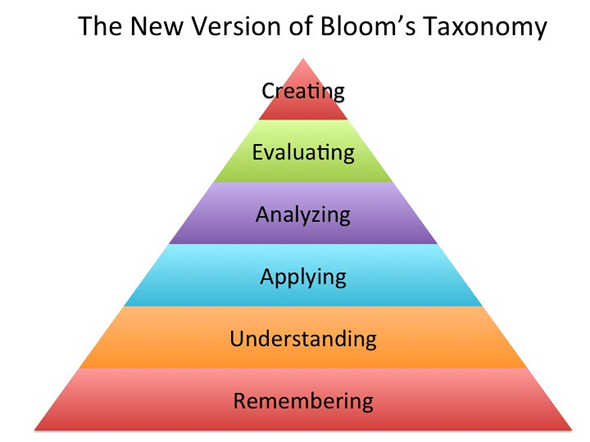

In 1956, Dr. Benjamin Bloom, an American educational psychologist who was particularly interested in how people learn, chaired a committee of educators that developed and classified a set of learning objectives, which came to be known as Bloom’s taxonomy. This classification system has been updated a little since it was first developed, but it remains important for both students and teachers in helping to understand the skills and structures involved in learning.

Bloom’s taxonomy divides the cognitive domain of learning into six main learning-skill levels, or learning-skill stages, which are arranged hierarchically—moving from the simplest of functions like remembering and understanding, to more complex learning skills, like applying and analyzing, to the most complex skills—evaluating and creating. The lower levels are more straightforward and fundamental, and the higher levels are more sophisticated. See Figure 5.3 below.

The following table describes the six main skillsets within the cognitive domain and gives you information on the level of learning expected for each. Read each description closely for details of what college-level work looks like in each domain. Note that the table begins with remembering, the lowest level of the taxonomy.

| Main Skill Levels Within the Cognitive Domain | Description | Examples of Related Learning Skills (Specific Actions Related to the Skillset) |

|---|---|---|

| Remembering | When you are skilled in remembering, you can recognize or recall knowledge you’ve already gained, and you can use it to produce or retrieve definitions, facts, and lists. Remembering may be how you studied in grade school or high school, but college will require you to do more with the information. | identify · relate · list · define · recall · memorize · repeat · record · name |

| Understanding | Understanding is the ability to grasp or construct meaning from oral, written, and graphic messages. Each college course will introduce you to new concepts, terms, processes, and functions. Once you gain a firm understanding of new information, you’ll find it easier to comprehend how or why something works. | restate · locate · report · recognize · explain · express · identify · discuss · describe · review · infer · illustrate · interpret · draw · represent · differentiate · conclude |

| Applying | When you apply, you use or implement learned material in new and concrete situations. In college, you will be tested or assessed on what you’ve learned in the previous levels. You will be asked to solve problems in new situations by applying knowledge and skills in new ways. You may need to relate abstract ideas to practical situations. | apply · relate · develop · translate · use · operate · organize · employ · restructure · interpret · demonstrate · illustrate · practice · calculate · show · exhibit · dramatize |

| Analyzing | When you analyze, you have the ability to break down or distinguish the parts of material into its components, so that its organizational structure may be better understood. At this level, you will have a clearer sense that you comprehend the content well. You will be able to answer questions such as what if, or why, or how something would work. | analyze · compare · probe · inquire · examine · contrast · categorize · differentiate · contrast · investigate · detect · survey · classify · deduce · experiment · scrutinize · discover · inspect · dissect · discriminate · separate |

| Evaluating | With skills in evaluating, you are able to judge, check, and even critique the value of material for a given purpose. At this level in college, you will be able to think critically, Your understanding of a concept or discipline will be profound. You may need to present and defend opinions. | judge · assess · compare · evaluate · conclude · measure · deduce · argue · decide · choose · rate · select · estimate · validate · consider · appraise · value · criticize · infer |

| Creating | With skills in creating, you are able to put parts together to form a coherent or unique new whole. You can reorganize elements into a new pattern or structure through generating, planning, or producing. Creating requires originality and inventiveness. It brings together all levels of learning to theorize, design, and test new products, concepts, or functions. | compose · produce · design · assemble · create · prepare · predict · modify · plan · invent · formulate · collect · generalize · document combine · relate · propose · develop · arrange · construct · organize · originate · derive · write |

Multiple Intelligences

When you learn, you may be using a variety of intelligences as explained in Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. Gardner proposes that there are nine different forms of intelligence, each of which functions independently of the others. Each person has a mix of all nine abilities—more of some and less of others—that helps to constitute that person’s individual cognitive profile. These nine intelligences are summarized in Table 5.2 below.

Since most tasks,—including learning in college,—require several forms of intelligence and can be completed in more than one way, it is possible for people with various profiles of talents to succeed on a task equally well. In writing an essay, for example, a student with high interpersonal intelligence but rather average verbal intelligence might use her interpersonal strength to get a lot of help and advice from classmates and the teacher. A student with the opposite profile might work well on his own but without the benefit of help from others. Both students might end up with essays that are good, but good for different reasons.

Multiple Intelligences According to Howard Gardner

| Form of intelligence | Examples of activities using the intelligence |

|---|---|

| Linguistic: Verbal skill; ability to use language well |

|

| Musical: Ability to create and understand music |

|

| Logical-Mathematical: logical skill; ability to reason, often using mathematics |

|

| Spatial: Ability to imagine and manipulate the arrangement of objects in the environment |

|

| Bodily-Kinesthetic: a sense of balance; coordination in use of one’s body |

|

| Interpersonal: Ability to discern others’ nonverbal feelings and thoughts |

|

| Intrapersonal: Sensitivity to one’s own thoughts and feelings |

|

| Naturalist: Sensitivity to subtle differences and patterns found in the natural environment |

|

| Existential: People’s ability to handle deep questions such as the meaning of existence. |

|

This model can be useful as a way for students to think about how you approach your learning. Multiple intelligences suggest that there is (or may be) more than one way to be “smart,” and that you can benefit from identifying your personal strengths and preferences.

Quick Quiz 5.1

- Explain what metacognition is.

- What are the stages of the learning process?

- What is the highest level of Bloom’s Taxonomy?

- Why is it important to know your multiple intelligences?

Licenses and Attribution

CC Licensed Content

- College Success by Amy Baldwin is licensed CC BY. Access for free.

References

- Arduini-Van Hoose, Nicole. Behaviorism and Motivation. Hudson Valley Community College, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/edpsy/chapter/behaviorism-and-motivation/. CC BY-NC-SA.

- Borich, Gary D., and Martin L. Tombari. Educational Psychology. CC BY.

- Bohlin. Educational Psychology. CC BY.

- Chiquo. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Wikimedia Commons, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/88/Maslow%27s_Hierarchy_of_Needs.jpg. CC BY-SA.

- —. Deficiency-Growth Theory: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Hudson Valley Community College, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/edpsy/chapter/deficiency-growth-theory/. CC BY-NC-SA.

- Duckworth, Angela L., et al. “Grit: Perseverance and Passion for Long-Term Goals.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 92, no. 6, June 2007, pp. 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087.

- Dweck, Carol S., and Ellen L. Leggett. “A Social-Cognitive Approach to Motivation and Personality.” Psychological Review, vol. 95, no. 2, 1988, pp. 256–273.

- —. Educational Psychology. OER Commons, https://www.oercommons.org/courses/edpsych/view.

- —. Expectancy-Value Theory. Hudson Valley Community College, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/edpsy/chapter/expectancy-value-theory/. CC BY-NC-SA.

- “Learning to Learn.” OER Commons, https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/73880/overview?section=5.

- Lucas, Laura, Heather Syrett, and Edgar Granillo. Personal Learning Preferences. Austin Community College. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- “Metacognition (Flavell).” Learning Theories, https://www.learning-theories.com/metacognition-flavell.html.

- Mindwerx. (n.d.). Four stages of learning competence [Image]. https://mindwerx.com/wp-content/uploads/Four-stages-of-learning-competence.jpg

- “Multiple Intelligences.” Educational Psychology, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/educationalpsychology/chapter/multiple-intelligences/. CC BY.

- —. Self-Determination Theory. Hudson Valley Community College. CC BY-NC-SA.

- —. Self-Efficacy Theory. Hudson Valley Community College, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/edpsy/chapter/self-efficacy-theory/. CC BY-NC-SA.

- —. Social Cognitive Learning Theory. Hudson Valley Community College.

- Spielman, Rose M., William J. Jenkins, and Marilyn D. Lovett. Psychology 2e. OpenStax, https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e. CC BY.

- Stoltz, Paul G. GRIT: The New Science of What It Takes to Persevere, Flourish, Succeed. ClimbStrong Press, 2014.

- —. Theories of Motivation. Hudson Valley Community College. CC BY-NC-SA.

- Thompson, Penny. Foundations of Educational Technology. CC BY-NC 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

- W. R. P. (2011, June 22). Bloom’s taxonomy [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/21847073@N05/5857112597