6.7 Taking Notes

Questions to consider:

- How can you prepare to take notes to maximize the effectiveness of the experience?

- What are some specific strategies you can employ for better notetaking?

- Why is annotating your notes after the notetaking session a critical step to follow?

Strong notes build on your prior knowledge of a subject, help you discuss trends or patterns present in the information, and direct you toward areas needing further research or reading.

It is not a good habit to transcribe every single word a speaker utters—even if you have an amazing ability to do that. Most of us do not have that court-reporter-esque skill level anyway, and if we try, we will end up missing valuable information. Learn to listen for main ideas and distinguish between these main ideas and details that typically support the ideas. Include examples that explain the main ideas.

The act of taking notes does not necessarily make you a successful learner. It is what you do with the notes later that makes your notes effective. Take your lecture notes and combine them with your textbook notes (yes, you need to take notes on both the lecture and the textbook). Then take time to organize your notes using one of many different styles—use the style that appeals to you or is most effective for your purpose. Typically, students take linear notes during a lecture, line after line of notes. However, linear notes are not effective to use during study time. You need to repackage your notes, using your selected style or a combination of styles, and then use them when you study.

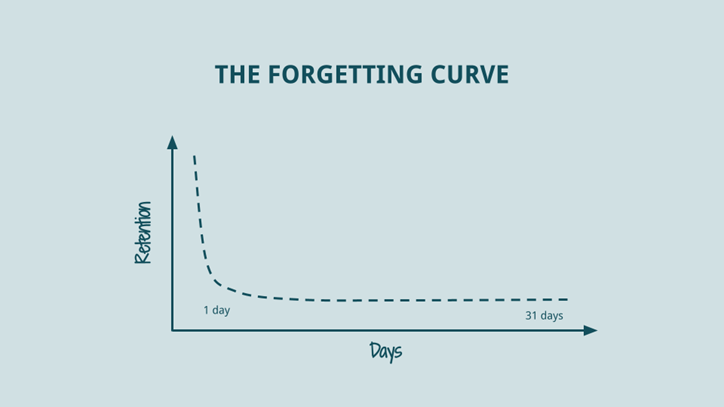

Think of all notes as potential study guides. In fact, if you only take notes without actively working on them after the initial notetaking session, the likelihood of the notes helping you is slim. Research on this topic concludes that without active engagement after taking notes, most students forget 60–75 percent of material over which they took the notes—within two days! That sort of defeats the purpose, don’t you think? This information about memory loss was first brought to light by 19th-century German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus. Fortunately, you do have the power to thwart what is sometimes called the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve by reinforcing what you learned through review at intervals shortly after you take in the material and frequently thereafter.

The very best notes are the ones you take in an organized manner that encourages frequent review and use as you progress through a topic or course of study. For this reason, you need to develop a way to organize all your notes for each class so they remain together and organized. As old-fashioned as it sounds, a clunky three-ring binder is an excellent organizational container for class notes. You can easily add to previous notes, insert handouts you may receive in class, and maintain a running collection of materials for each separate course. If the idea of carrying around a heavy binder has you rolling your eyes, then transfer that same structure into your computer files. If you do not organize your many documents into some semblance of order on your computer, you will waste significant time searching for improperly named or saved files.

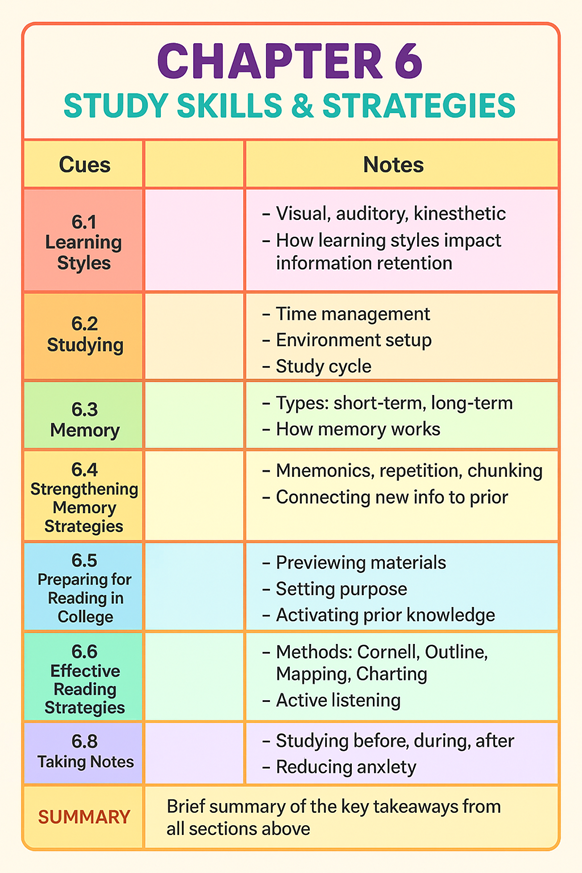

Notetaking Strategies

You may have a standard way you take all your notes for all your classes. When you were in high school, this one-size-fits-all approach may have worked. Now that you are in college, reading and studying more advanced topics, your general method may still work some of the time, but you should have some different strategies in place if you find that your method is not working as well with college content. You probably will need to adopt different notetaking strategies for different subjects. The strategies in this section represent various ways to take notes in such a way that you are able to study after the initial notetaking session.

Cornell Method

One of the most recognizable notetaking systems is called the Cornell Method, a relatively simple way to take effective notes devised by Cornell University education professor Dr. Walter Pauk in the 1940s. In this system, you take a standard piece of note paper and divide it into three sections by drawing a horizontal line across your paper about one to two inches from the bottom of the page (the summary area) and then drawing a vertical line to separate the rest of the page above this bottom area, making the left side about two inches (the recall column) and leaving the biggest area to the right of your vertical line (the notes column). You may want to make one page and then copy as many pages as you think you will need for any particular class, but one advantage of this system is that you can generate the sections quickly. The Cornell Method provides you with a well-organized set of notes that will help you study and review your notes as you move through the course. If you are taking notes on your computer, you can still use the Cornell Method in Word or Excel by creating your own or by using a template. See Appendix 6 for a blank form.

Now that you have the notetaking format generated, the beauty of the Cornell Method is its organized simplicity. Just write on one side of the page (the right-hand notes column)—this will help later when you are reviewing and revising your notes. During your notetaking session, use the notes column to record information over the main points and concepts of the lecture; try to put the ideas into your own words, which will help you not transcribe the speaker’s words verbatim. Skip lines between each idea in this column. Avoid writing in complete sentences.

As soon as possible after your notetaking session, preferably within eight hours but no more than twenty-four hours, read over your notes column and fill in any details you missed in class, including the places where you indicated you wanted to expand your notes. Then in the recall column, write any key ideas from the corresponding notes column—just add the one- or two-word main ideas. These words in the recall column serve as cues to help you remember the detailed information you recorded in the notes column.

Once you are satisfied with your notes, summarize this page of notes in two or three sentences using the summary area at the bottom of the sheet. Now, before you move onto something else, cover the large notes column, and quiz yourself over the key ideas. Repeat this step often as you go along, not just immediately before an exam, and you will help your memory make the connections between your notes, your textbook reading, your in-class work, and assignments that you need to succeed on any quizzes and exams.

Outlining

Other note organizing systems may help you in different disciplines. You can take notes in a formal outline if you prefer, using Roman numerals for each new topic, moving down a line to capital letters indented a few spaces to the right for concepts related to the previous topic, then adding details to support the concepts indented a few more spaces over and denoted by an Arabic numeral.

You do not absolutely have to use the formal numerals and letters, but you have to be careful to indent so you can tell when you move from a higher-level topic to the related concepts and then to the supporting information. The main benefit of an outline is how organized it is.

The following formal outline example shows the basic pattern:

Taking Notes (main topic–usually general)

- Note taking strategies (concept related to main topic)

- Cornell Method (supporting info about the concept)

- Outlining

- Chart of table

- Concept Mapping and Visual Notetaking

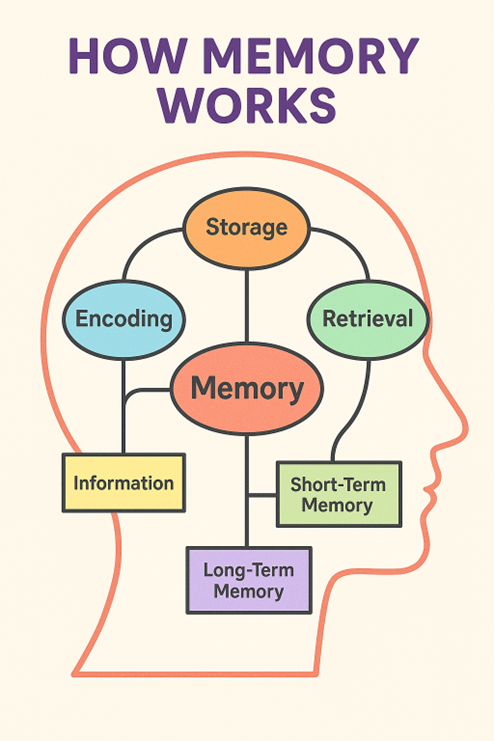

Memory (main topic)

- Working Memory

- Short Term Memory

- Long Term Memory

- Obstacles to Memory

- Lack of Sleep

Chart or table

Similar to creating an outline, you can develop a chart to compare or contrast main ideas in a notetaking session. Divide your paper into four or five columns with headings that include either the main topics covered in the lecture or categories such as How, What, When, Advantages/Pros, Disadvantages/Cons, or other divisions of the information. You write your notes into the appropriate columns as that information comes to light in the presentation.

Academic Skills Needed for Success in College

| Types | Details | Additional Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Styles | |||

| Studying | |||

| Memory | |||

| Reading |

This format helps you pull out the salient ideas and establishes an organized set of notes to study later. (If you have not noticed that this reviewing later idea is a constant across all notetaking systems, you should…take note of that.) Notes by themselves that you never reference again are little more than scribblings. That would be a bit like compiling an extensive grocery list, so you stay on budget when you shop, work all week on it, and then just throw it away before you get to the store. You may be able to recall a few items but likely will not be as efficient as you could be if you had the notes to reference. Just as you cannot read all the many books, articles, and documents you need to peruse for your college classes, you cannot remember the most important ideas of all the notes you will take as part of your courses, so you must review.

Concept Mapping and Visual Notetaking

One final notetaking method that appeals to learners who prefer a visual representation of notes is called mapping or sometimes mind mapping or concept mapping, although each of these names can have slightly different uses. Variations of this method abound, so you may want to look for more versions online, but the basic principles are that you are making connections between main ideas through a graphic depiction; some can get rather elaborate with colors and shapes, but a simple version may be more useful at least to begin. Main ideas can be circled or placed in a box with supporting concepts radiating off these ideas shown with a connecting line and possibly details of the support further radiating off the concepts.

You may be interested in trying visual notetaking or adding pictures to your notes for clarity. Sometimes when you cannot come up with the exact wording to explain something or you’re trying to add information for complex ideas in your notes, sketching a rough image of the idea can help you remember. According to educator Sherrill Knezel in an article entitled “The Power of Visual Notetaking,” this strategy is effective because “When students use images and text in notetaking, it gives them two different ways to pull up the information, doubling their chances of recall.” Do not shy away from this creative approach to notetaking just because you believe you aren’t an artist; the images do not need to be perfect. You may want to watch Rachel Smith’s TEDx Talk called “Drawing in Class” to learn more about visual notetaking.

You can play with different types of notetaking suggestions and find the method(s) you like best, but once you find what works for you, stick with it. You will become more efficient with the method the more you use it, and your notetaking, review, and test prep will become, if not easier, certainly more organized, which can delete decrease your anxiety.

Quick Quiz 6.7

- Explain why organizing and reviewing your notes is just as important as taking them in the first place.

- Compare and contrast at least two notetaking strategies discussed in the reading.

Licenses and Attribution

CC Licensed Content

- College Success by Amy Baldwin is licensed CC BY. Access for free.

- Psychology by Rose M. Spielman is licensed CC BY. Access for free.

References

- Abel, M., & Bäuml, K.-H. T. (2013). Sleep can reduce proactive interference. Memory, 22(4), 332–339. doi:10.1080/09658211.2013.785570. Retrieved from http://www.psychologie.uni-regensburg.de/Baeuml/papers_in_press/sleepPI.pdf

- Bellezza, F. S. (1981). Mnemonic devices: Classification, characteristics and criteria. Review of Educational Research, 51, 247–275.

- Bodie, G. D., Powers, W. G., & Fitch-Hauser, M. (2006). Chunking, priming, and active learning: Toward an innovative approach to teaching communication-related skills. Interactive Learning Environment, 14(2), 119–135.

- Craik, F. I. M., & Watkins, M. J. (1973). The role of rehearsal in short-term memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12, 599–607.

- English106. (n.d.). [Photograph of handwritten notes and pen on notebook]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/english106/

- Learning to learn. (n.d.). OER Commons. https://oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/73880/overview?section=4

Images or Graphic Elements

- Images used by permission from Alamo Colleges District Department of Communications.