3.5. Time Management

Before continuing, take a few minutes to assess how you are doing now in terms of reaching your goals.

Activity 3.6: Assessing Progress Toward Goals

|

|

Yes |

Unsure |

No |

|

1. I have clear, realistic, attainable goals for the short and long term, including for my educational success. |

|

|

|

|

2. I have a good sense of priorities that helps ensure I always get the important things done, including my studies, while balancing my time among school, work, and social life. |

|

|

|

|

3. I have a positive attitude toward being successful in college. |

|

|

|

|

4. I know how to stay focused and motivated so I can reach my goals. |

|

|

|

|

5. When setbacks occur, I work to solve the problems effectively and then move on. |

|

|

|

|

6. I have a good space for studying and use my space to avoid distractions. |

|

|

|

|

7. I do not attempt to multitask when studying. |

|

|

|

|

8. I schedule my study periods at times when I am at my best. |

|

|

|

|

9. I use a weekly or daily planner to schedule study periods and other tasks in advance and to manage my time well. |

|

|

|

|

10. I am successful at not putting off my studying and other important activities or being distracted by other things. |

|

|

|

Where Do You Want to Go?

Think about how you answered the questions above. Be honest with yourself. On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate how well you stay focused on your goals and use your time?

|

|

|

|

Need to improve |

|

|

|

Very successful |

|||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

In the following list, circle the three most important areas in which you think you need to improve:

- Setting goals

- Staying focused on goals

- Keeping strong priorities

- Maintaining a positive attitude

- Staying motivated for academic work

- Solving and preventing problems

- Having an organized space for studies

- Avoiding the distractions of technology

- Preventing distractions caused by other people

- Managing time well when studying

- Overcoming a tendency to put things off

- Using a planner to schedule study periods

- Using a to-do list to ensure all tasks are done

- Finding enough time to do everything

Organizing Your Space

Now that you’ve worked up an attitude for success and are feeling motivated, it’s time to get organized. You need to organize both your space and your time.

Space is important for many reasons—some obvious, some less so. People’s moods, attitudes, and levels of work productivity change in different spaces. Learning to use space to your own advantage helps get you off to a good start in your studies. Here are a few of the ways space matters:

- Everyone needs his or her own space. This may seem simple, but everyone needs some physical area, regardless of size, that is really his or her own—even if it’s only a small part of a shared space. Within your own space, you generally feel more secure and in control.

- Physical space reinforces habits. For example, using your bed primarily for sleeping makes it easier to fall asleep there than elsewhere and makes it not a good place to try to stay awake and alert for studying.

- Different places create different moods. While this may seem obvious, students don’t always use places to their best advantage. One place may be bright and full of energy, with happy students passing through and enjoying themselves—a place that puts you in a good mood. But that may make it more difficult to concentrate on your studying. Yet the opposite—a totally quiet, austere place devoid of color and sound and pleasant decorations—can be just as unproductive if it makes you associate studying with something unpleasant. Everyone needs to discover what space works best for himself or herself—and then let that space reinforce good study habits.

Use Space to Your Advantage and to Avoid Distractions

Begin by analyzing your needs, preferences, and past problems with places for studying. Where do you usually study? What are the best things about that place for studying? What distractions are most likely to occur there?

The goal is to find, or create the best place for studying, and then to use it regularly so that studying there becomes a good habit.

- Choose a place you can associate with studying. Make sure it’s not a place already associated with other activities (eating, watching television, sleeping, etc.). Over time, the more often you study in this space, the stronger will be its association with studying, so that eventually you’ll be completely focused as soon as you reach that place and begin.

- Your study area should be available whenever you need it. If you want to use your home, apartment, or dorm room but you never know if another person may be there and possibly distracting you, then it’s probably better to look for another place, such as a study lounge or an area in the library.

Figure 2.2

Choose a pleasant, quiet place for studying, such as the college library. clemsonunivlibrary – Students Study in 4 West (https://www.flickr.com/photos/clemsonunivlibrary/5032701615/). – CC BY-NC 2.0.

- Your study space should meet your study needs. An open desk or table surface usually works best for writing, and you’ll tire quickly if you try to write notes sitting in an easy chair (which might also make you sleepy). You need good light for reading, to avoid tiring from eyestrain. If you use a laptop for writing notes or reading and researching, you need a power outlet, so you don’t have to stop when your battery runs out.

- Your study space should meet your psychological needs. Some students may need total silence with no visual distractions; they may find a perfect study carrel hidden away on the fifth floor in the library. Other students may be unable to concentrate for long without looking up from reading and momentarily letting their eyes move over a pleasant scene. Experiment to find the setting that works best for you—and remember that the more often you use this same space, the more comfortable and effective your studying will become.

- You may need the support of others to maintain your study space. Students living at home, whether with a spouse and children or with their parents, often need the support of family members to maintain an effective study space. The kitchen table probably isn’t best if others pass by frequently. Be creative, if necessary, and set up a card table in a quiet corner of your bedroom or elsewhere to avoid interruptions. Put a “do not disturb” sign on your door.

- Keep your space organized and free of distractions. You want to prevent sudden impulses to neaten up the area (when you should be studying), do laundry, wash dishes, and so on. Unplug a nearby telephone, turn off your cell phone, and use your computer only as needed for studying. If your e-mail or message program pops up a notice every time an e-mail or message arrives, turn off your Wi-Fi or detach the network cable to prevent those intrusions.

- Plan for breaks. Everyone needs to take a break occasionally when studying. Think about the space you’re in and how to use it when you need a break. If in your home, stop and do a few exercises to get your blood flowing. If in the library, take a walk up a couple flights of stairs and around the stacks before returning to your study area.

- Prepare for human interruptions. Even if you hide in the library to study, there’s a chance a friend may happen by. At home with family members or in a dorm room or common space, the odds increase greatly. Have a plan ready in case someone pops in and asks you to join them in some fun activity. Know when you want to finish your studying so that you can create a study time for later—or for tomorrow at a specific time.

The Distractions of Technology

Multitasking is the term commonly used for being engaged in two or more different activities at the same time, usually referring to activities using devices such as cell phones, computers, and so on. Many people claim to be able to do as many as four or five things simultaneously, such as writing an e-mail while responding to a text, all while watching a video on their computer monitor or talking on the phone. Many people who have grown up with computers consider this kind of multitasking a normal way to get things done, including studying. Even people in business sometimes speak of multitasking as an essential component of today’s fast-paced world.

It is true that some things can be attended to while you’re doing something else, such as checking e-mail while you watch television news—but only when none of those things demands your full attention. You can concentrate 80 percent on the e-mail, for example, while 20 percent of your attention is listening for something on the news that catches your attention.

Then you turn to the television for a minute, watch that segment, and go back to the e-mail. But you’re not actually watching the television at the same time you’re composing the e-mail— you’re rapidly going back and forth. The mind can focus only on one thing at any given moment. Even things that don’t require much thinking are severely impacted by multitasking, such as driving while talking on a cell phone or texting. An astonishing number of people end up in the emergency room from just trying to walk down the sidewalk while texting, so common is it now to walk into a pole or parked car while multitasking!

“Okay,” you might be thinking, “why should it matter if I write my paper first and then answer e-mails or do them back and forth at the same time?” It takes you longer to do two or more things at the same time than if you do them separately—at least with anything that you have to focus on, such as studying. That’s true because each time you go back to studying after looking away to a message or tweet, it takes time for your mind to shift gears to get back to where you were. Every time your attention shifts, add up some more “downtime”— and soon it’s evident that multitasking is costing you a lot more time than you think. And that’s assuming your mind does fully shift back to where you were every time, without losing your train of thought or forgetting an important detail. It doesn’t always.

The other problem with multitasking is the effect it can have on the attention span—and even on how the brain works. Scientists have shown that in people who constantly shift their attention from one thing to another in short bursts, the brain forms patterns that make it more difficult to keep sustained attention on any one thing. So, when you really do need to concentrate for a while on one thing, such as when studying for a big test, it becomes more difficult to do even if you’re not multitasking at that time. It’s as if your mind makes a habit of wandering from one thing to another and then can’t stop. Figure 2.3

Multitasking makes studying much less effective. Benton Greene

– Multitasking (https://www.flickr.com/photos/beezum88/2220050655/). – CC BY 2.0.

So, stay away from multitasking whenever you have something important to do, like studying. If it’s already a habit for you, don’t let it become worse. Manipulate your study space to prevent the temptations altogether. Turn your computer off—or shut down e-mail and messaging programs if you need the computer for studying. Turn your cell phone off—if you just tell yourself not to answer it but still glance at it each time to see who sent or left a message, you’re still losing your studying momentum and must start over again. For those who are really addicted to technology (you know who you are!), go to the library and don’t take your laptop or cell phone.

In the later section in this chapter on scheduling your study periods, we recommend scheduling breaks as well, usually for a few minutes every hour. If you’re really hooked on checking for messages, plan to do that at scheduled times.

Family and Roommate Issues

Sometimes going to the library or elsewhere is not practical for studying, and you need to find a way to cope in a shared space.

Part of the solution is time management. Agree with others on certain times that will be reserved for studying; agree to keep the place quiet, not to have guests visiting, and to prevent other distractions. These arrangements can be made with a sibling, roommate, spouse, and older children. If there are younger children in your household and you have child-care responsibility, it’s usually more complicated. You may have to schedule your studying during their nap time or find quiet activities for them to enjoy while you study. Try to spend some time with your kids before you study, so they don’t feel like you’re ignoring them. (More tips are offered later in this chapter.)

The key is to plan. You don’t want to find yourself, the night before an exam, in a place that offers no space for studying.

Finally, accept that sometimes you’ll just have to say no. If your roommate or a friend often tries to engage you in conversation or suggests doing something else when you need to study, just say no. Learn to be firm but polite as you explain that you just really must get your work done first. Students who live at home may also have to learn how to say no to parents or family members—just be sure to explain the importance of the studying you need to do! Remember, you can’t be everything to everyone all the time.

Organizing Your Time

This is the most important part of this chapter. When you know what you want to do, why not just sit down and get it done? The millions of people who complain frequently about “not having enough time” would love it if it were that simple!

Time management isn’t difficult, but you do need to learn how to do it well.

Time and Your Personality

People’s attitudes toward time vary widely. One person seems to be always rushing around but gets less done than another person who seems unconcerned about time and calmly goes about the day. Since there are so many different “time personalities,” it’s important to realize how you approach time. Start by trying to figure out how you spend your time during a typical week, using Activity 3.7.

Activity 3.7: Where Does the Time Go?

See if you can account for a week’s worth of time. For each of the activity categories listed, make your best estimate of how many hours you spend in a week. (For categories that are about the same every day, just estimate for one day and multiply by seven for that line.)

|

Category of activity |

Number of hours per week |

|

Sleeping |

|

|

Eating (including preparing food) |

|

|

Personal hygiene (i.e., bathing, etc.) |

|

|

Working (employment) |

|

|

Volunteer service or internship |

|

|

Chores, cleaning, errands, shopping, etc. |

|

|

Attending class |

|

|

Studying, reading, and researching (outside of class) |

|

|

Transportation to work or school |

|

|

Getting to classes (walking, biking, etc.) |

|

|

Organized group activities (clubs, church services, etc.) |

|

|

Time with friends (include television, video games, etc.) |

|

|

Attending events (movies, parties, etc.) |

|

|

Time alone (include television, video games, surfing the Web, etc.) |

|

|

Exercise or sports activities |

|

|

Reading for fun or other interests done alone |

|

|

Talking on phone, texting, social media, etc. |

|

|

Other—specify: ________________________ |

|

Now use your calculator to total your estimated hours. Is your number larger or smaller than 168, the total number of hours in a week? If your estimate is higher, go back through your list and adjust numbers to be more realistic. But if your estimated hours total fewer than 168, don’t just go back and add more time in certain categories. Instead, ponder this question: Where does the time go? We’ll come back to this question.

Think about your time analysis in Activity 3.7. People who estimate too high often feel they don’t have enough time. They may have time anxiety and often feel frustrated. People at the other extreme, who often can’t account for how they use all their time, may have a more relaxed attitude. They may not actually have more free time, but they may be wasting more time than they want to admit with less important things. Yet they still may complain about how much time they spend studying, as if there’s a shortage of time.

People also differ in how they respond to schedule changes. Some go with the flow and accept changes easily, while others function well only when following a planned schedule and may become upset if that schedule changes. If you do not react well to an unexpected disruption in your schedule, plan extra time for catching up if something throws you off. This is all part of understanding your time personality.

Another aspect of your time personality involves time of day. If you need to concentrate, such as when writing a class paper, are you more alert and focused in the morning, afternoon, or evening? Do you concentrate best when you look forward to a relaxing activity later, or do you study better when you’ve finished all other activities? Do you function well if you get up early—or stay up late—to accomplish a task? How does that affect the rest of your day or the next day? Understanding this will help you better plan your study periods.

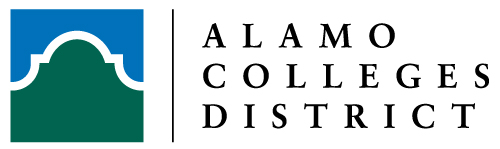

While you may not be able to change your “time personality,” you can learn to manage your time more successfully. The key is to be realistic. The best way to know how you spend your time is to record what you do all day in a time log, every day for a week, and then add that up. Print out a copy of the time log in Figure 2.4 “Daily Time Log” and carry it with you. Every so often, fill in what you have been doing. Do this for a week before adding up the times; then enter the total hours in the categories in Activity 3.7. You might be surprised that you spend a lot more time than you thought just hanging out with friends or surfing the Web or using social media or any of the many other things people do. You might find that you study well early in the morning even though you thought you are a night person, or vice versa. You might learn how long you can continue at a specific task before needing a break.

Figure 2.4 Daily Time Log

If you have work and family responsibilities, you may already know where many of your hours go. Although we all wish we had “more time,” the important thing is what we do with the time we have. Time management strategies can help us better use the time we do have by creating a schedule that works for our own time personality.

Time Management

Time management for successful college studying involves these factors:

- Determining how much time you need to spend studying

- Knowing how much time you actually have for studying and increasing that time if needed

- Being aware of the times of day you are at your best and most focused

- Using effective long- and short-term study strategies

- Scheduling study activities in realistic segments

- Using a system to plan ahead and set priorities

- Staying motivated to follow your plan and avoid procrastination

For every hour in the classroom, college students should spend on average, about two hours outside of class, reading, studying, writing papers, and so on. If you’re a full-time student with fifteen hours a week in class, then you need another thirty hours for rest of your academic work. That forty-five hour is about the same as a typical full-time job. If you work part time, time management skills are even more essential. These skills are still more important for parttime college students who work full time and commute or have a family. To succeed in college, virtually everyone must develop effective strategies for dealing with time.

Look back at the number of hours you wrote in Activity 3.7 for a week of studying. Do you have two hours of study time for every hour in class? Many students do not know this much time is needed, so don’t be surprised if you underestimated this number of hours. Remember this is just an average amount of study time—you may need more or less for your own courses.

To reserve this study time, you may need to adjust how much time you spend in other activities. Activity 3.8 will help you figure out what your typical week should look like.

Activity 3.8: Where Should Your Time Go?

First, fill in the time needed each week to complete the required activities. Then, subtotal your hours and subtract that number from 168. Now, portion out the remaining hours for the discretionary activities (things that don’t have to do with school, work, or a healthy life).

|

Category of activity |

Number of hours per week |

|

Required Activities |

|

|

Attending class |

|

|

Studying, reading, and researching (outside of class) |

|

|

Working (employment) |

|

|

Volunteer service or internship |

|

|

Category of activity |

Number of hours per week |

|

Required Activities |

|

|

Sleeping |

|

|

Eating (including preparing food) |

|

|

Personal hygiene (i.e., bathing, etc.) |

|

|

Chores, cleaning, errands, shopping, etc. |

|

|

Transportation to work or school |

|

|

Getting to classes (walking, biking, etc.) |

|

|

Childcare |

|

|

Subtotal: |

|

|

|

168 – _______ = _______ |

|

Discretionary activities |

|

|

Organized group activities (clubs, church services, etc.) |

|

|

Time with friends (include television, video games, etc.) |

|

|

Attending events (movies, parties, etc.) |

|

|

Time alone (include television, video games, surfing the Web, etc.) |

|

|

Exercise or sports activities |

|

|

Reading for fun or other interests done alone |

|

|

Talking on phone, texting, social media, etc. |

|

|

Other—specify: ________________________ |

|

|

Other—specify: ________________________ |

|

Note: If you find you have almost no time left for discretionary activities, you may be overestimating how much time you need for eating, errands, and the like. Use the time log in Figure 2.4 “Daily Time Log” to determine if you really must spend that much time on those things.

Activity 3.8 shows most college students that they do have plenty of time for their studies without losing sleep or giving up their social life. But you may have less time for discretionary activities than in the past. Something somewhere must give. That’s part of time management— and why it’s important to keep your goals and priorities in mind. The other part is to learn how to use the hours you do have as effectively as possible, especially the study hours. For example, if you’re a typical college freshman who plans to study for three hours in an evening but then procrastinates, gets caught up in a conversation, loses time to checking e-mail and text messages, and daydreams while reading a textbook, then maybe you spent four hours “studying” but got only two hours of actual work done. So, you end up behind and feeling like you’re still studying way too much. The goal of time management is to get three hours of studying done in three hours and have time for your life as well.

Special note for students who work and/or have a family. You may have almost no discretionary time at all left in Activity 3.8 after all your “must-do” activities. If so, you may have overextended yourself—a situation that inevitably will lead to problems. You can’t sleep two hours less every night for the whole school year, for example, without becoming ill or unable to concentrate well on work and school. It is better to recognize this situation now rather than set yourself up for a very difficult term and possible failure. If you cannot cut the number of hours for work or other obligations, see your academic advisor right away. It is better to take fewer classes and succeed than to take more classes than you have time for and risk failure.

Time Management Strategies for Success

Following are some strategies you can begin using immediately to make the most of your time:

- Prepare to be successful. When planning for studying, think yourself into the right mood. Focus on the positive. “When I get these chapters read tonight, I’ll be ahead in studying for the next test, and I’ll also have plenty of time tomorrow to do X.” Visualize yourself studying well!

- Use your best—and most appropriate—time of day. Different tasks require different mental skills. Some kinds of studying you may be able to start first thing in the morning as you wake, while others need your most alert moments at another time.

- Break up large projects into small pieces. Whether it’s writing a paper for class, studying for a final exam, or reading a long assignment or full book, students often feel daunted at the beginning of a large project. It’s easier to get going if you break it up into stages that you schedule at separate times—and then begin with the first section that requires only an hour or two.

- Do the most important studying first. When two or more things require your attention, do the more crucial one first. If something happens and you can’t complete everything, you’ll suffer less if the most crucial work is done.

- If you have trouble getting started, do an easier task first. Like large tasks, complex or difficult ones can be daunting. If you can’t get going, switch to an easier task you can accomplish quickly. That will give you momentum, and often you feel more confident tackling the difficult task after being successful in the first one.

- If you’re feeling overwhelmed and stressed because you have too much to do, revisit your time planner. Sometimes it’s hard to get started if you keep thinking about other things you need to get done. Review your schedule for the next few days and make sure everything important is scheduled, then relax and concentrate on the task at hand.

- If you’re really floundering, talk to someone. Maybe you just don’t understand what you should be doing. Talk with your instructor or another student in the class to get back on track.

- Take a break. We all need breaks to help us concentrate without becoming fatigued and burned out. As a rule, a short break every hour or so is effective in helping recharge your study energy. Get up and move around to get your blood flowing, clear your thoughts, and work off stress.

- Use unscheduled times to work ahead. You’ve scheduled those hundred pages of reading for later today, but you have the textbook with you as you’re waiting for the bus. Start reading now or flip through the chapter to get a sense of what you’ll be reading later. Either way, you’ll save time later. You may be amazed how much studying you can get done during downtimes throughout the day.

- Keep your momentum. Prevent distractions, such as multitasking, that will only slow you down. Check for messages, for example, only at scheduled break times.

- Reward yourself. It’s not easy to sit still for hours of studying. When you successfully complete the task, you should feel good and deserve a small reward. A healthy snack, a quick video game session, or social activity can help you feel even better about your successful use of time.

- Just say no. Always tell others nearby when you’re studying, to reduce the chances of being interrupted. Still, interruptions happen, and if you are in a situation where you are frequently interrupted by a family member, spouse, roommate, or friend, it helps to have your “no” prepared in advance: “No, I really have to be ready for this test” or “That’s a great idea, but let’s do it tomorrow—I just can’t today.” You shouldn’t feel bad about saying no—especially if you explained to that person in advance that you needed to study.

- Have a life. Never schedule your day or week so full of work and study that you have no time at all for yourself, your family and friends, and your larger life.

- Use a calendar planner and daily to-do list. We’ll look at these time management tools in the next section.

Battling Procrastination

Procrastination is a way of thinking that lets one put off doing something that should be done now. This can happen to anyone at any time. It’s like a voice inside your head keeps coming up with these brilliant ideas for things to do right now other than studying: “I really ought to get this room cleaned up before I study” or “I can study anytime, but tonight’s the only chance I have to do X.” That voice is also very good at rationalizing: “I really don’t need to read that chapter now; I’ll have plenty of time tomorrow at lunch.…”

Procrastination is very powerful. Some people battle it daily, others only occasionally. Most college students procrastinate often, and about half say they need help avoiding procrastination. Procrastination can threaten one’s ability to do well on an assignment or test.

People procrastinate for different reasons. Some people are too relaxed in their priorities, seldom worry, and easily put off responsibilities. Others worry constantly, and that stress keeps them from focusing on the task at hand. Some procrastinate because they fear failure; others procrastinate because they fear success or are so perfectionistic that they don’t want to let themselves down. Some are dreamers. Many different factors are involved, and there are different styles of procrastinating.

Just as there are different causes, there are different possible solutions for procrastination. Different strategies work for different people. The time management strategies described earlier can help you avoid procrastination. Because this is a psychological issue, some additional psychological strategies can also help:

- Since procrastination is usually a habit, accept that and work on breaking it as you would any other bad habit: one day at a time. Know that every time you overcome feelings of procrastination, the habit becomes weaker—and eventually you’ll have a new habit of being able to start studying right away.

- Schedule times for studying using a daily or weekly planner. Carry it with you and look at it often. Just being aware of the time and what you need to do today can help you get organized and stay on track.

- If you keep thinking of something else you might forget to do later (making you feel like you “must” do it now), write yourself a note about it for later and get it out of your mind.

- Counter a negative with a positive. If you’re procrastinating because you’re not looking forward to a certain task, try to think of the positive future results of doing the work.

- Counter a negative with a worse negative. If thinking about the positive results of completing the task doesn’t motivate you to get started, think about what could happen if you keep procrastinating. You’ll have to study tomorrow instead of doing something fun you had planned. Or you could fail the test. Some people can jolt themselves right out of procrastination.

- On the other hand, fear causes procrastination in some people—so don’t dwell on the thought of failing. If you’re studying for a test, and you’re so afraid of failing it that you can’t focus on studying and you start procrastinating, try to put things in perspective. Even if it’s your most difficult class and you don’t understand everything about the topic, that doesn’t mean you’ll fail, even if you may not receive an A or a B.

- Study with a motivated friend. Form a study group with other students who are motivated and won’t procrastinate along with you. You’ll learn good habits from them while getting the work done now.

- Keep a study journal. At least once a day write an entry about how you have used your time and whether you succeeded with your schedule for the day. If not, identify what factors kept you from doing your work. This journal will help you see your own habits and distractions so that you can avoid things that lead to procrastination.

- Get help. If you really can’t stay on track with your study schedule, or if you’re always putting things off until the last minute, see a college counselor. They have lots of experience with this common student problem and can help you find ways to overcome this habit.

Calendar Planners and To-Do Lists

Calendar planners and to-do lists are effective ways to organize your time. Many types of academic planners are commercially available (check your college bookstore), or you can make your own. Some people like a page for each day, and some like a week at a time. Some use computer calendars or phone apps. Almost any system will work well if you use it consistently.

Some college students think they don’t need to write down their schedule and daily to-do lists. They’ve always kept it in their head before, so why write it down in a planner now? Some students were talking about this one day in a study group, and one bragged that she had never had to write down her calendar because she never forgot dates. Another student reminded her how she’d forgotten a preregistration date and missed taking a course she really wanted because the class was full by the time she went online to register. “Well,” she said, “except for that time, I never forget anything!” Of course, none of us ever forgets anything—until we do.

Calendars and planners help you look ahead and write in important dates and deadlines, so you don’t forget. But it’s just as important to use the planner to schedule your own time, not just deadlines. For example, you’ll learn later that the most effective way to study for an exam is to study in several short periods over several days. You can easily do this by choosing time slots in your weekly planner over several days that you will commit to studying for this test. You don’t need to fill every time slot, or to schedule everything that you do, but the more carefully and consistently you use your planner, the more successfully will you manage your time.

But a planner cannot contain everything that may occur in a day. We’d go crazy if we tried to schedule every telephone call, every e-mail, every bill to pay, every trip to the grocery store. For these items, we use a to-do list, which may be kept on a separate page in the planner.

Activity 3.9: Academic Calendar

Using a monthly calendar, fill it in for the semester. Start by checking the syllabus for each of your courses and write important dates on the calendar. Write in all exams and deadlines. You should also include big events, such as birthdays and weddings, on this calendar so you can plan study time around them. Many students find it helpful to post this semester academic calendar on the wall in front of their study space or by the exit door so that they will constantly be reminded of what is coming up.

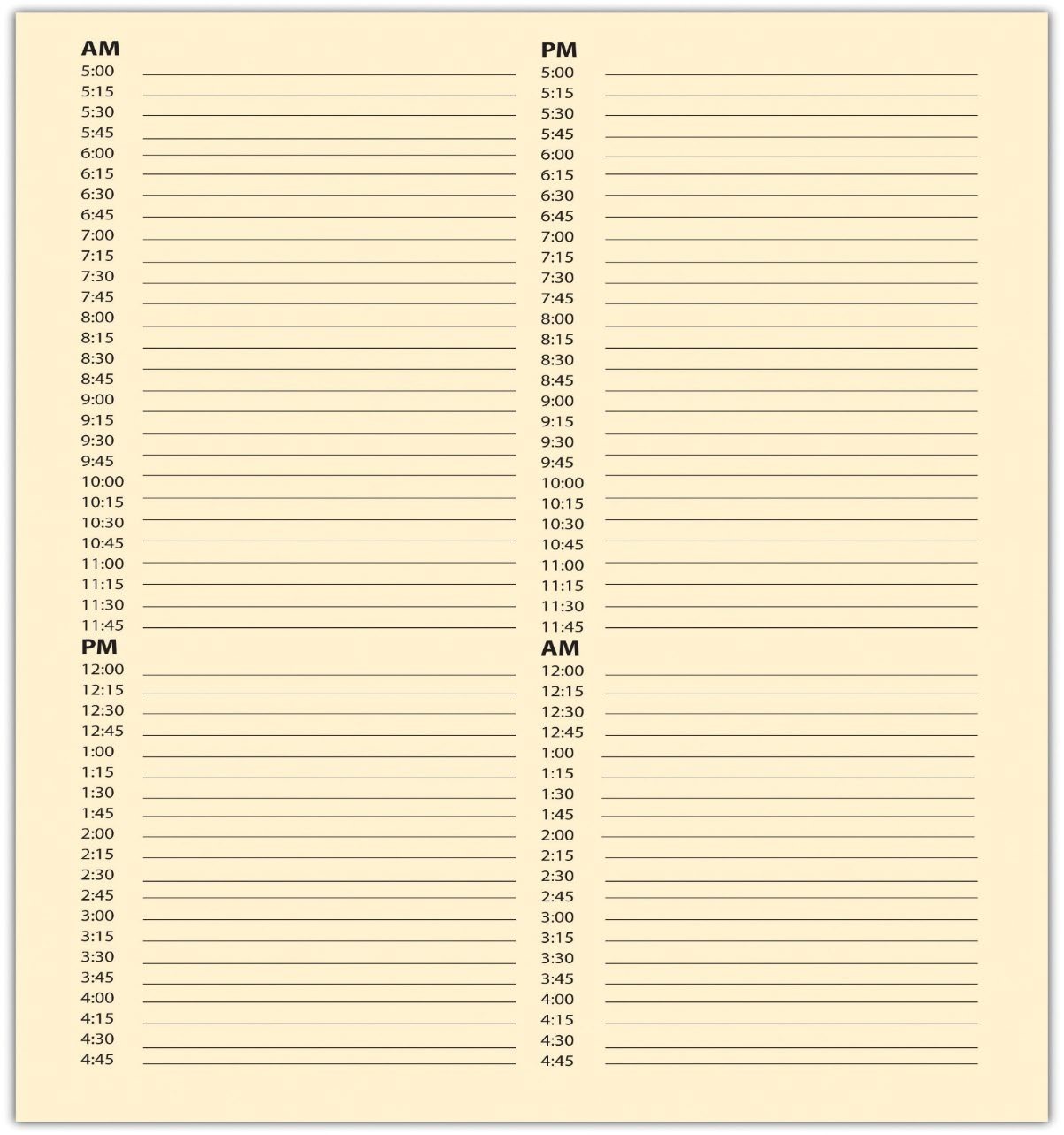

Activity 3.10: Weekly Planner

Print a Weekly Planner form found in Figure 2.5. Fill in this planner form for next week. First write in all your class meeting times; your work or volunteer schedule; and your usual hours for sleep, family activities, and any other activities at fixed times. Don’t forget time needed for transportation, meals, and so on. Make sure to schedule in study time. Any blocks of “free time” that are left over are available for discretionary activities.

Figure 2.5 Weekly Planner

Remember that for every hour spent in class, plan an average of two hours studying outside of class. These are the time periods you now want to schedule in your planner. These times change from week to week, with one course requiring more time in one week because of a paper due at the end of the week and a different course requiring more the next week because of a major exam. Make sure you block out enough hours in the week to accomplish what you need to do. As you choose your study times, consider what times of day you are at your best and what times you prefer to use for social or other activities.

Don’t try to micromanage your schedule. Don’t try to estimate exactly how many minutes you’ll need two weeks from today to read a given textbook chapter. Instead, just choose the blocks of time you will use for your studies. Don’t yet write in the exact study activity—just reserve the block. Next, look at the major deadlines for projects and exams that you wrote in earlier. Estimate how much time you may need for each and work backward on the schedule from the due date.

For example, you have a short paper due on Friday. You determine that you’ll spend ten hours total on it, from initial brainstorming and planning through to drafting and revising. Since you have other things also going on that week, you want to get an early start; you might choose to block an hour a week ahead on Saturday morning, to brainstorm your topic, and jot some preliminary notes. Monday evening is a good time to spend two hours on the next step or prewriting activities. Since you have a lot of time open Tuesday afternoon, you decide that’s the best time to reserve to write the first draft; you block out three or four hours. You make a note on the schedule to leave time open that afternoon to see your instructor during office hours in case you have any questions on the paper; if not, you’ll finish the draft or start revising.

Thursday, you schedule a last block of time to revise and polish the final draft due tomorrow.

Here are some more tips for successful schedule planning:

- Studying is often most effective immediately after a class meeting. If your schedule allows, block out appropriate study time after class periods.

- Be realistic about time when you make your schedule. If your class runs to four o’clock and it takes you twenty minutes to wrap things up and reach your study location, don’t figure you’ll have a full hour of study between four o’clock and five o’clock.

- Don’t overdo it. Few people can study four or five hours nonstop, and scheduling extended time periods like that may just set you up for failure.

- Schedule social events that occur at set times, but just leave holes in the schedule for other activities. Enjoy those open times and recharge your energies!

- Try to schedule some time for exercise at least three days a week.

- Plan to use your time between classes wisely. If three days a week you have the same hour free between two classes, what should you do with those three hours? Maybe you need to eat, walk across campus, or run an errand. But say you have an average forty minutes free at that time on each day. Instead of just frittering the time away, use it to review your notes from the previous class or for the coming class or to read a short assignment. Over the whole term, that forty minutes three times a week adds up to a lot of study time.

- If a study activity is taking longer than you had scheduled, look ahead and adjust your weekly planner to prevent the stress of feeling behind.

- If you maintain your schedule on your computer or smartphone, it’s still a good idea to print and carry it with you. Don’t risk losing valuable study time if you’re away from the device.

- If you’re not paying close attention to everything in your planner, use a colored highlighter to mark the times blocked out for important things.

- When following your schedule, pay attention to starting and stopping times. If you planned to start your test review at four o’clock after an hour of reading for a different class, don’t let the reading run long and take time away from studying for the test.

Your Daily To-Do List

People use to-do lists in different ways, and you should find what works best for you. As with your planner, consistent use of your to-do list will make it an effective habit.

Some people prefer not to carry their planner everywhere but instead copy the key information for the day onto a to-do list. Using this approach, your daily to-do list starts out with your key scheduled activities and then adds other things you hope to do today.

Some people use their to-do list only for things not on their planner, such as short errands, phone calls or e-mail, and the like. This still includes important things—but they’re not scheduled out for specific times.

Although we call it a daily list, the to-do list can also include things you may not get to today but don’t want to forget about. Keeping these things on the list, even if they’re a low priority, helps ensure that eventually you’ll get to it.

Start every day with a fresh to-do list written down or in a to-do app on your phone. Check your planner for key activities for the day and check yesterday’s list for items remaining.

Some items won’t require much time, but other activities such as assignments will. If you finish lunch and have twenty-five minutes left before your next class, what things on the list can you do now and check off?

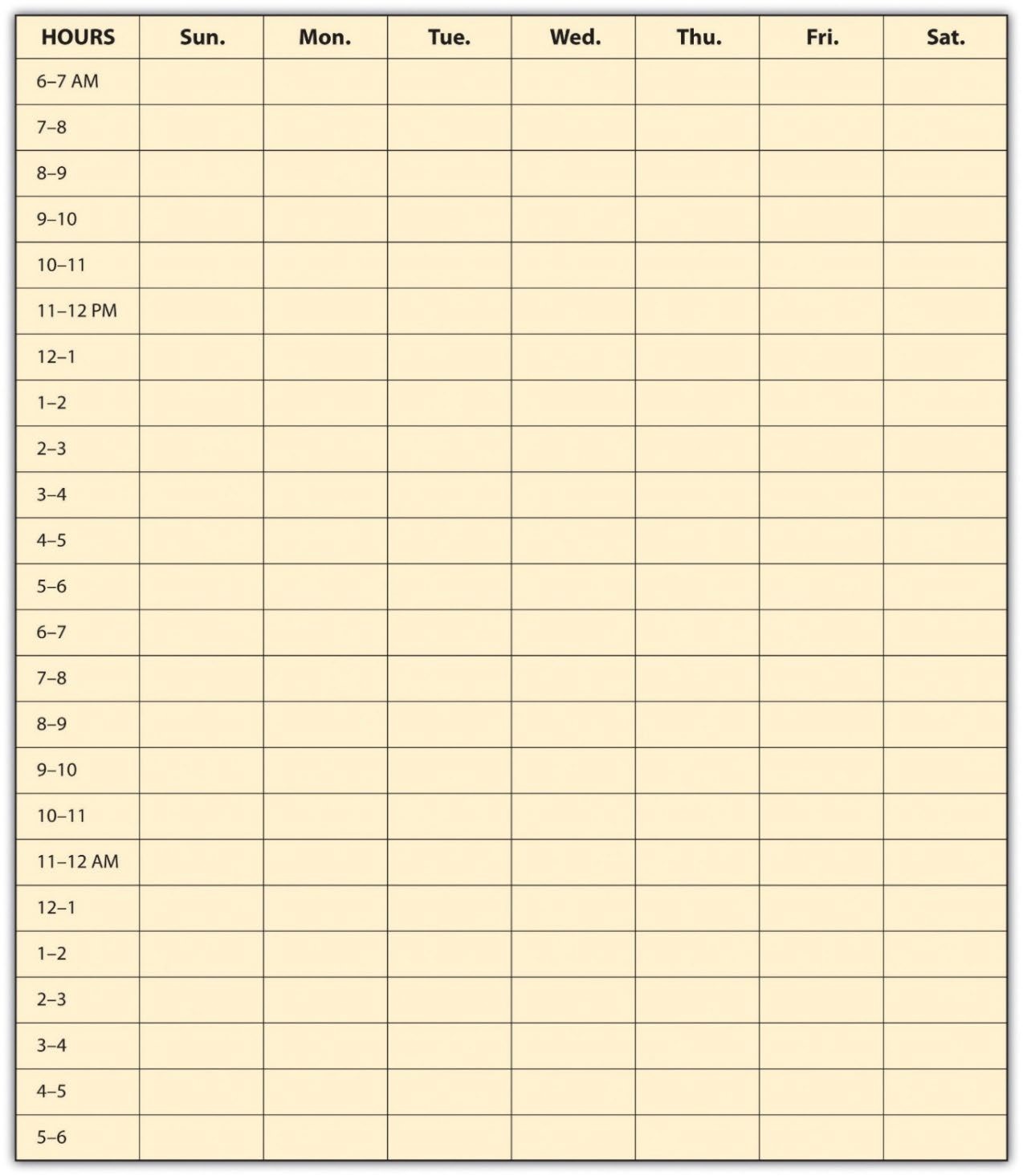

Finally, use some system to prioritize things on your list. Some students use a 1, 2, 3 or A, B, C rating system for importance. Others simply highlight or circle items that are critical to get done today. Figure 2.7 “Examples of Two Different Students’ To-Do Lists” shows two different to-do lists—each very different but each effective for the student using it.

Figure 2.7 Examples of Two Different Students’ To-Do Lists

Use whatever format works best for you to prioritize or highlight the most important activities.

Here are some more tips for effectively using your daily to-do list:

- Be specific: “Read history chapter 2 (30 pages)”—not “History homework.”

- Put important things high on your list where you’ll see them every time you check the list.

- Make your list at the same time every day so that it becomes a habit.

- Don’t make your list overwhelming. If you added everything you eventually need to do, you could end up with so many things on the list that you’d never read through them all. If you worry you might forget something, write it in the margin of your planner’s page a week or two away.

- Use your list. Lists often include little things that may take only a few minutes to do, so check your list any time during the day you have a moment free.

- Cross out or check off things after you’ve done them—doing this becomes rewarding.

- Don’t use your to-do list to procrastinate. Don’t pull it out to find something else you just “have” to do instead of studying!

Time Management Tips for Students Who Work

If you’re both working and taking classes, you seldom have large blocks of free time. Avoid temptations to stay up very late studying, for losing sleep can lead to a downward spiral in performance at both work and school. Instead, try to follow these guidelines:

- If possible, adjust your work or sleep hours so that you don’t spend your most productive times at work. If your job offers flex time, arrange your schedule to be free to study at times when you perform best.

- Try to arrange your class and work schedules to minimize commuting time. If you are a part-time student taking two classes, taking classes back-to-back two or three days a week uses less time than spreading them out over four or five days. Working four ten-hour days rather than five eight-hour days reduces time lost to travel, getting ready for work, and so on.

- If you can’t arrange an effective schedule for classes and work, consider online courses that allow you to do most of the work on your own time.

- Use your daily and weekly planner conscientiously. Any time you have thirty minutes or more free, schedule a study activity.

- Consider your “body clock” when you schedule activities. Plan easier tasks for those times when you’re often fatigued and reserve alert times for more demanding tasks.

- Look for any “hidden” time potentials. Maybe you prefer the thirty-minute drive to work over a forty-five-minute bus ride. But if you can read on the bus, that’s a gain of ninety minutes every day at the cost of thirty minutes longer travel time. An hour a day can make a huge difference in your studies.

- Can you do quick study tasks during slow times at work? Take your class notes with you and use even five minutes of free time wisely.

- Remember your long-term goals. You need to work, but you also want to finish your college program. If you have the opportunity to volunteer for some overtime, consider whether it’s really worth it. Sure, the extra money would help, but could the extra time put you at risk for not doing well in your classes?

- Be as organized on the job as you are academically. Use your planner and to-do list for work matters, too. The better organized you are at work, the less stress you’ll feel—and the more successful you’ll be as a student also.

- If you have a family as well as a job, your time is even more limited. In addition to the previous tips, try some of the strategies that follow.

Time Management Tips for Students with Family

Living with family members often introduces additional time stresses. You may have family obligations that require careful time management. Use all the strategies described earlier, including family time in your daily plans the same as you would hours spent at work. Don’t assume that you’ll be “free” every hour you are home, because family events or a family member’s need for your assistance may occur at unexpected times. Schedule your important academic work well ahead and in blocks of time you control. See also the earlier suggestions for controlling your space: you may need to use the library or another space to ensure you are not interrupted or distracted during important study times.

Students with their own families are likely to feel time pressures. After all, you can’t just tell your partner or kids that you’ll see them in a couple years when you’re not so busy with job and college! In addition to all the planning and study strategies discussed so far, you also need to manage your family relationships and time spent with family. While there’s no magical solution for making more hours in the day, even with this added time pressure there are ways to balance your life well:

- Talk everything over with your family. If you’re going back to school, your family members may not have realized changes will occur. Don’t let them be shocked by sudden household changes. Keep communication lines open so that your partner and children feel they’re together with you in this new adventure. Eventually you will need their support.

- Work to enjoy your time together, whatever you’re doing. You may not have as much time together as previously but cherish the time you do have—even if it’s washing dishes together or cleaning house. If you’ve been studying for two hours and need a break, spend the next ten minutes with family instead of checking e-mail or watching television. Ultimately, the important thing is being together, not going out to movies or dinners or the special things you used to do when you had more time. Look forward to being with family and appreciate every moment you are together, and they will share your attitude.

- Combine activities to get the most out of time. Don’t let your children watch television or play video games off by themselves while you’re cooking dinner, or you may find you have only twenty minutes family time together while eating. Instead, bring the family together in the kitchen and give everyone something to do. You can have a lot of fun together and share the day’s experiences, and you won’t feel so bad then if you must go off and study by yourself.

- Share the load. Even children who are very young can help with household chores to give you more time. Attitude is everything: try to make it fun, the whole family pulling together—not something they “have” to do and may resent, just because Mom or Dad went back to school. (Remember, your kids will reach college age someday, and you want them to have a good attitude about college.) As they get older, they can do their own laundry, cook meals, and get themselves off to school, and older teens can run errands and do the grocery shopping. They will gain in the process by becoming more responsible and independent.

- Schedule your study time based on family activities. If you face interruptions from young children in the early evening, use that time for something simple like reviewing class notes. When you need more quiet time for concentrated reading, wait until they’ve gone to bed.

- Be creative with childcare. Usually options are available, possibly involving extended family members, sitters, older siblings, cooperative childcare with other adult students, as well as child-care centers.

This is a derivative of COLLEGE SUCCESS by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution, which was originally released and is used under CC BY-NC-SA. This work, unless otherwise expressly stated, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site..